Leaders of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) say they are being hit by unique challenges as the coronavirus pandemic takes its toll on communities and finances.

Sending students home meant a loss of room and board fees, while the switch to online learning brought additional costs for colleges.

The reduced income and extra spending were even more significant for HBCUs. They generally have smaller endowments that can be used as a financial buffer and also rely more on in-person experiences.

Quinton Ross, president of Alabama State University, said some institutions were faced with a lack of technological set-up for online learning and a need to help students returning to homes where they may not have had computers or connectivity.

“We had to rush to try to provide and undergird ourselves with technology [and] many of the infrastructures are not up to par,” he said.

The adjustment has been costly. Without providing precise figures, Ross estimated the impact of the coronavirus so far on ASU has been “in the millions.”

The financial structure of many HBCUs has left them especially vulnerable, the college heads say.

Within both public and private sectors, HBCU endowments lag behind those of non-HBCUs by at least 70%, a recent report by the American Council on Education found last year.

Instead, HBCUs as well as Hispanic-serving institutions and community colleges rely heavily on their year-to-year enrollments, said Virginia State University President Makola Abdullah.

“We are largely tuition-driven, and we are largely dependent on the level of financial aid help that our students can get from their Pell grant, from the state and from philanthropy,” he said. “And so it puts us in a slightly different situation in that our level of reserves would be lower.”

He added: “We’re all in the same storm, but we’re not all in the same boat.”

Morehouse College in Atlanta is anticipating enrollment will drop by up to 25% because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Its president, David Thomas, said the earnings or responsibilities of every employee would be affected as a result of the impact of the virus added to an existing budget shortfall. There will be job losses, pay cuts and furloughs.

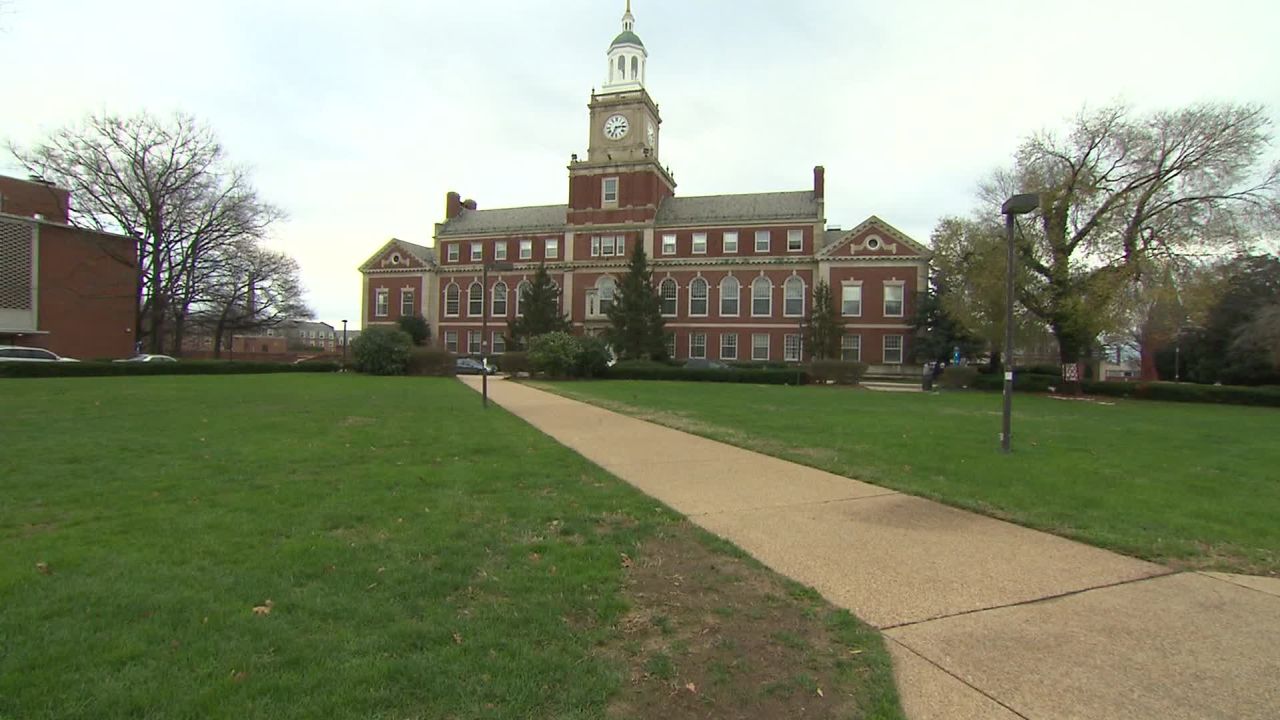

Wayne Frederick, president of Howard University in Washington, said endowments are not a panacea, though he said “the situation is 10 times worse” for those institutions without them.

“Even the schools with large endowments are suggesting that the crashing economy, and the fact that there’s so much restricted money in their endowment, that they can’t use those endowments to fix their financial situation,” he said in an interview with CNN.

Howard’s budget is now being adjusted for an estimated $39 million shortfall in revenues, which includes $6 million refunded to students, Frederick said in a letter to his college community.

Last month, the Department of Education allocated $1.4 billion in relief funding specifically to institutions serving minority populations, including HBCUs. The money was part of the aid package authorized by Congress.

Some alumni of HBCUs in Congress, like Rep. Alma Adams of North Carolina, are working on securing more money in the next relief package that is being discussed. “We’re trying to be trying to be creative and figure out how we can weather this storm,” she said.

But Arthur Brigati, vice president of institutional advancement at Miles College, an HBCU liberal arts institution in Alabama, told CNN that while the $1.4 billion and other aid for higher education earmarked by Congess and approved by the President was “fantastic,” it was only a first step in putting the fire out. “Things still smolder,” he said.

Abdullah of Virginia State said the financial impact of the pandemic was again raising fears that colleges could go under. “We are very concerned that without the adequate federal and state support, many institutions that serve the underserved might not be around,” he said.

Data already suggests that the percentage of low-income students seeking federal student aid is decreasing – a sign that they may not be in a financial position to return to school in the fall. Financial applications for the 2020-21 school year from the lowest-income students are down 8.2% – or nearly 250,000 students – according to data from the National College Attainment Network.

The applications had been on track to be comparable to last year, until March 15 when completions started to decline while lockdowns spread across the country.

Frederick remains optimistic, noting registration for the fall at Howard is currently up and that when the job market is tight, some may see college as a better option.

But he and his colleagues recognize that much is unknown – such as how much teaching can be in person this fall. Traditionally, culture on HBCU campuses has been a draw for prospective students, and so the question becomes whether they will attend if the experience looks vastly different.

“I tell most parents and students, one of the reasons you come to Howard is because 20% of what you’re going to get is an excellent education in the classroom,” Frederick said. “But 80% of the time you spend is going to be outside interacting with people, interacting with the culture, the experience. And so taking that away is problematic.”