Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the nation was in the throes of another public health crisis: the opioid epidemic.

More than 2 million Americans struggle with opioid use disorder, and about 130 Americans on average die every day from an opioid overdose. Opioids account for a majority of drug overdose deaths, the leading cause of accidental death in the US. It’s a crisis that’s been a priority for officials at the federal, state and local levels for years.

Now, the coronavirus has disrupted all matters of life across the country – including efforts to combat the nation’s opioid problem.

Walk-in clinics and syringe exchange programs have been closed. Community support groups are meetingvirtually.

Some who struggle with substance abuse are homeless or incarcerated and can’t comply with social distancing guidelines, while those who can are left isolated and at risk. On top of all that, the pandemic is causing massive stress – a primary driver of relapse.

“This changing, very strange world that we’re living through could serve as a trigger for people to return to drug use,” said Daliah Heller, director of drug use initiatives at the public health organization Vital Strategies. “And that brings a great potential for overdose with it.”

As local officials report spikes in overdose calls and deaths, experts and advocates say they’re concerned the coronavirus pandemic is making an already serious problem worse.

Local officials are reporting overdose spikes

County coroners, law enforcement and emergency responders around the country are reporting spikes in overdose calls and deaths – and they’re concerned that’s connected to Covid-19.

Franklin County, Ohio, reported 28 non-fatal overdoses from last Friday night to Saturday night. The previous Friday, the county had six overdose deaths, which coroner Anahi Ortiz had described as a “surge” in a Facebook post.

Ortiz wrote in a Facebook post on Sunday that Franklin County had seen a 50% increase in fatal overdoses from January to April 15.Sixty-two people died of overdoses in the month of April alone, she wrote.

Niagara County in New York reported last month that drug overdoses spiked 35% from January 1 to April 6, compared to the same time last year.

And in Jacksonville, Florida, the fire and rescue chief said the city saw a 20% increase in overdose calls from February to March.

It’s too soon to determine whether such reports are evidence of a larger trend, said Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Federal and state data on fatal and non-fatal overdoses for the past few months are not yet available, while coroners and medical examiners are overwhelmed with cases of Covid-19 and may not have the resources to follow up on overdose deaths, she said.

“We do not know,” Volkow said, of whether more people are overdosing in connection with Covid-19. “In many cases, we will likely never know.”

But she predicts that some communities will “absolutely” see an uptick in overdoses.

Public health services are disrupted

There are a few reasons that experts are concerned about a potential coronavirus-related increase in opioid overdoses.

For one, harm reduction programs across the country have beenexperiencing reduced capacity given the pandemic, Heller said.

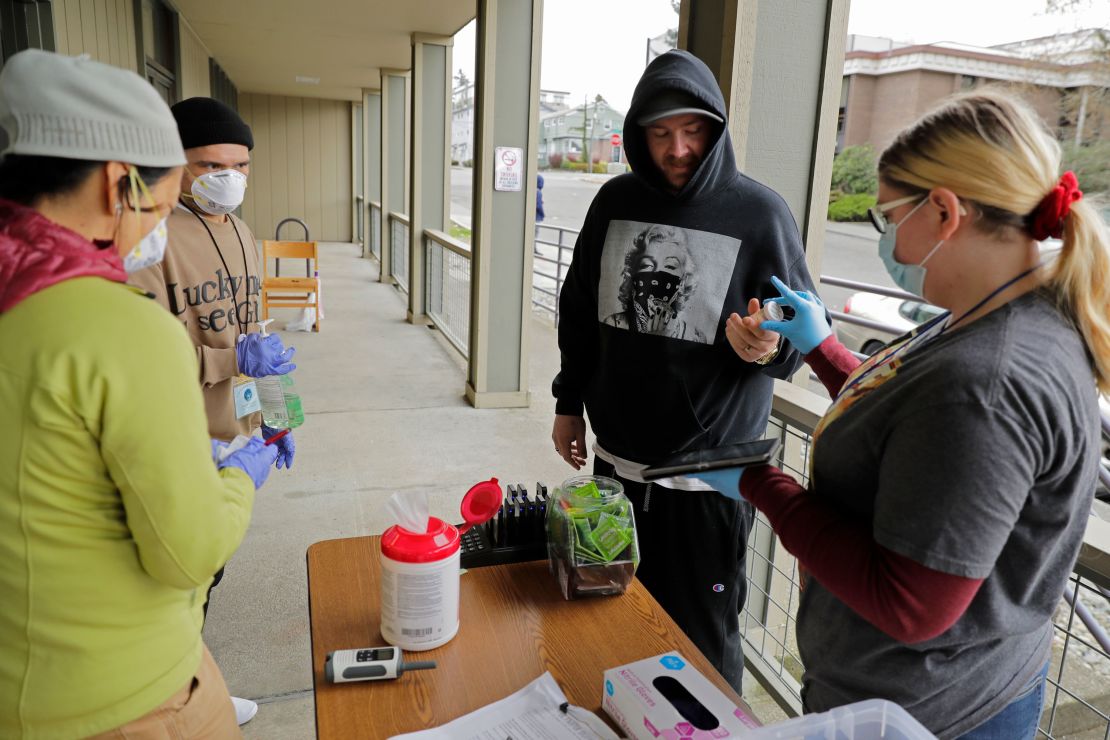

Though many states have defined such services as essential in their stay-at-home orders, some programs have had to restrict access or reduce staffing because of a lack of funding or personal protective equipment for their workers.

Federal agencies have eased some regulations that have mitigated the risks of overdoses and Covid-19 infection, Heller said.

For example, patients receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder often have to visit a provider daily for a dose of methadone. But because such visits could expose both patients and health care workers to Covid-19, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is temporarily allowing treatment programs to provide patients with two to four weeks’ worth of methadone doses to take home.

Meanwhile, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has also relaxed telehealth restrictions around prescriptions for buprenorphine, another medication-assisted treatment.

Still, for people who lack health insurance or high-speed internet access, there are barriers.

People are engaging risky behaviors

In some communities, services that treat addiction or prevent overdoses, such as needle exchange programs, are on hold – leading people to engage in risky behaviors.

Jamie Favaro is the founder of Next Distro, a harm reduction organization that provides syringes and the overdose-reversing naloxone online and through the mail. She said her organization is receiving about five times as many requests as usual because people haven’t had access to sterile syringes. A significant volume of requests is coming from people in Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia, she said.

Recently, she said, a client in West Virginia requested syringes after sharing a single needle with three other people for a week. The exchange programs in their area were shut down, the client said, and there was nowhere else to get syringes. Other clients have reached out saying they are also reusing syringes or have had needles break off in their skin, she said.

“I’m very fearful that we’re going to see an HIV spike and a Hepatitis C spike, as well as an overdose spike in areas where the needle exchange programs have shut down,” Favaro said.

More harm reduction programs around the country are beginning to mail syringes and naloxone to people who use opioids, Favaro added. County health departments are ramping up naloxone distribution to protect against overdoses too.

But the coronavirus pandemic presents challenges there as well.

When someone overdoses on opioids, another person generally administers naloxone to reverse those effects. Because of social distancing, Volkow said, it’s possible that some individuals may not have anyone else around to administer the life-saving medication.

The drug supply is affected

Another reason people are at heightened risk of opioid overdoses has to do with how Covid-19 has affected the nation’s illicit drug supply, experts say.

Illegal drugs are typically smuggled into the US from other countries, but border restrictions brought on by the pandemic could theoretically decrease drug access in some areas, Volkow said.

On the surface, Heller said, that might seem like a good thing. But a limited supply could drive dealers to increase the potency of products to meet demand, mixing powerful, synthetic opioids like fentanyl into drugs and putting those who use them at a greater risk of overdose.

Less access to drugs could also drive users to seek out other, unfamiliar drug sources – or risk withdrawal.

Stress could drive people to relapse

Finally, the social isolation brought on by the coronavirus pandemic is leaving people especially vulnerable.

Some support groups for people experiencing opioid addiction or for those in recovery are now taking place over Zoom, Volkow said. But the virtual contact often just isn’t the same.

“One of the most powerful interventions is to keep people in treatment is that social network,” she said. “Isolation can lead you to seek out some relief, like starting to take drugs.”

It will be a while before we know the true effects that Covid-19 has had on those who struggle with opioid use disorders, Volkow said. But already, there are many reasons to worry.