Editor’s Note: We are publishing personal essays from CNN’s global staff as they live and cover the story of Covid-19. Ivan Watson is a senior international correspondent for CNN in Hong Kong.

“Can we take our masks off?” I ask, as my bride and I get into position.

“You may,” responds a Hong Kong official, who is still wearing his mask.

Moments later, Rana and I exchange rings, sign government documents, and share a brief kiss. Amid the uncertainty of the coronavirus pandemic, Rana and I have just gotten married.

On the other side of the planet, our families and friends in the US, Lebanon and elsewhere watch the little civil ceremony in Hong Kong streamed live on Instagram, sprinkling the video with hearts and emojis and other social media expressions of happiness.

Before leaving the wedding registry, we put on his and hers surgical masks adorned with the titles “Mr.” and “Mrs.”

This was not what we expected, when I first asked her to marry me on a freezing night in New York City last December.

At the time, we were both jet-lagged after the long flight from Hong Kong, where we live and work. We were also deliriously happy, posing in front of a glowing fountain alongside my sister and brother-in-law, who conspired with me to take surprise photos of the occasion.

Basking in that happy moment, we had little clue that a deadly new strain of pneumonia had just been discovered in a city called Wuhan in China – and the next four and a half months of our lives became our Engagement with Coronavirus.

Neither of us are strangers to crisis.

Rana grew up in Beirut in a civil war. At a young age, she suffered the loss of her father, one of many tragic victims of that conflict.

While my childhood was much more comfortable, 20 years of reporting overseas exposed me to the grim realities of war, natural disaster and political instability.

Still, neither of us had ever been confronted by a modern-day plague of global proportions.

The wake-up call came at the end of January, when the Hong Kong administration canceled schools, shut down public recreation centers and issued work-from-home orders to civil servants. The coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan had spread across China, and the first cases had been detected in the semi-autonomous cities of Hong Kong and Macau.

Hong Kongers didn’t mess around. Immediately, the whole city started wearing masks.

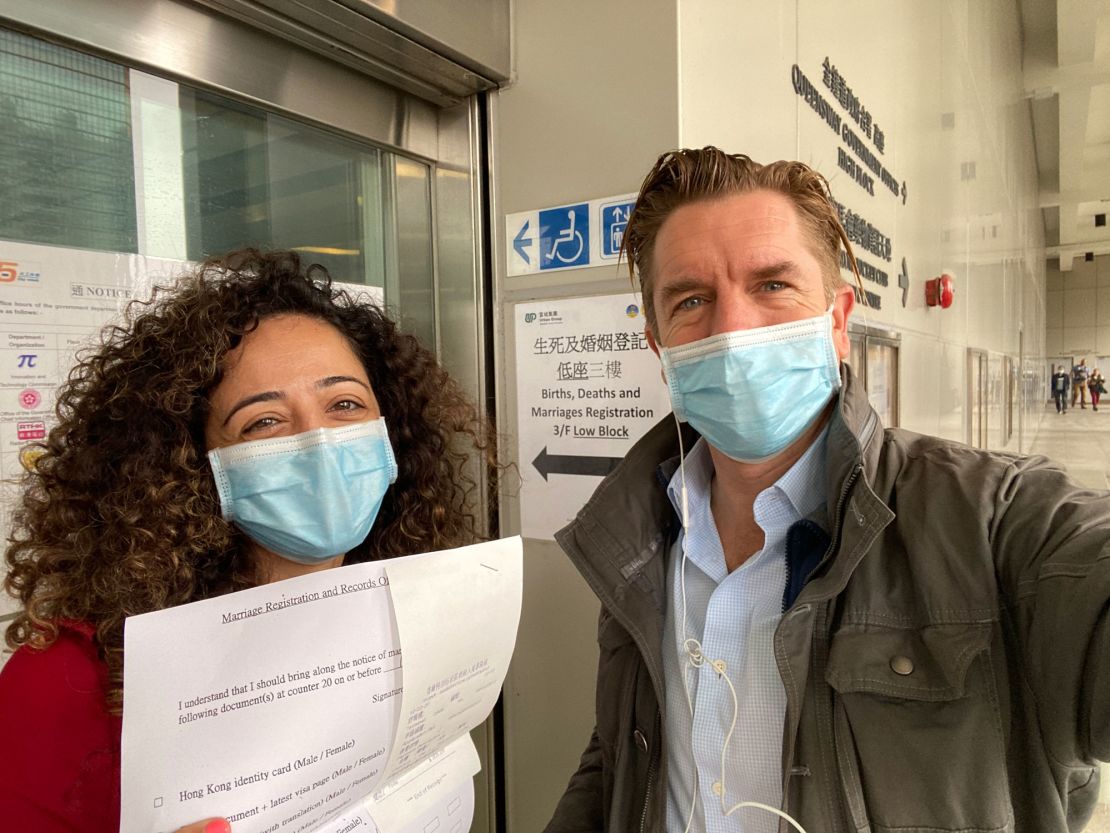

We did too, when we went to the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registrations Office in early February to apply for a date to get married.

Friends and family back home called to express concern about our health. But they spoke about the epidemic as if it was some distant threat, an “Asian” problem that would never reach their shores.

As Rana became more and more worried, I remained naively optimistic – until a reporting assignment in South Korea at the end of February.

At that stage, South Korea had the most confirmed coronavirus cases outside mainland China. In early March, thousands of Koreans were testing positive on a daily basis. Governments increasingly imposed international flight restrictions. Seemingly overnight, my hotel in Seoul became eerily empty.

On March 10, the only way to get from South Korea back home to Hong Kong was to fly absurdly long distances via London. On the flight from South Korea, CNN cameraman Tom Booth and I were shocked to see British Airways crews operating without any protection. No one checked our temperature during the layover at London’s Heathrow Airport. Britain apparently behaved as if this deadly disease wasn’t happening.

Upon arrival in Hong Kong, health authorities put me on two-week mandatory medical surveillance. I was to check my temperature twice daily and report immediately if I came down with symptoms. Though authorities advised against it, Rana insisted on staying by my side throughout the 14 days. Fortunately, neither of us got sick.

Making the best of it

Then, throughout March, Covid-19 spread like wildfire across the Middle East, Europe and North America. Suddenly, Rana and I were far more worried about our parents in the US and Lebanon, than we were for ourselves in Hong Kong.

For two people who have lived almost all of our adult lives overseas, a sickening realization set in – we could no longer count on jumping on a plane to fly home to our loved ones in the event of an emergency.

Yet amid the anxiety and fear, a silver lining emerged.

In this pandemic, we had each other. Social isolation meant a pause in business travel and long work deployments.

With our little rescue cat, our small family settled in for weeks of working from home in pajamas followed by cozy home-cooked dinners.

The coronavirus forced us to stop and count our blessings. The entire world has been taught a giant lesson in humility, a reminder that we are subject to forces and events that we cannot control. Nothing – neither our health, the roof over our heads, nor the food on our table – can be taken for granted.

At the same time, life must go on.

“After all, your grandparents got married during World War II,” my mom pointed out.

She is very right. My grandparents, two refugees from the civil war in Russia, started a family amid the horrors of Nazi-occupied France.

Compare that to me and Rana, who spent much of our engagement on the couch watching “Tiger King” (among other things).

So far, we have had it so easy. A week before the wedding, however, disaster struck. Rana’s 84-year old grandmother suffered a stroke. She was taken to intensive care in Beirut and had brain surgery.

There was nothing we could do. Even if there was some way to fly to Lebanon, Rana would not dare exposing her family if she picked up an illness on the plane.

Thankfully, Rana’s teta stabilized after the operation. She’s a tough lady.

Finally, our wedding day arrived in May. We wore surgical masks with “bride” and “groom” written on them in marker to the registry.

The city’s coronavirus guidelines allow up to 20 guests at a wedding. We had eight.

There is no time for vows to be exchanged during the 15-minute civil ceremony – although in some ways, we didn’t need them.

After our engagement with coronavirus, we know we will be there for each other, no matter what the future may bring.