Alvin Yau is exhausted. Like other residents in Hong Kong, he hasn’t had a break in nearly a year,ricocheting from one crisis to the next.

When Hong Kong was consumed by anti-government, pro-democracy protests last year, the 25-year-old banking analyst found himself constantly on edge, unable to sleep at night, and so overwhelmed he once burst into tears in the middle of the street.

The political chaos began calming somewhat in December – but only weeks later, the first reports emerged of a mysterious new virus across the border in mainland China.

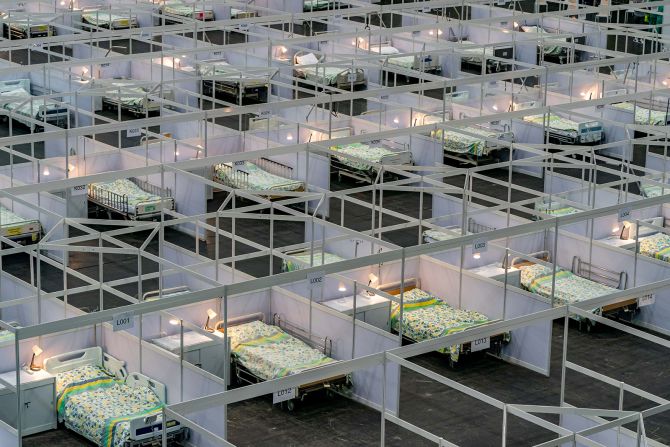

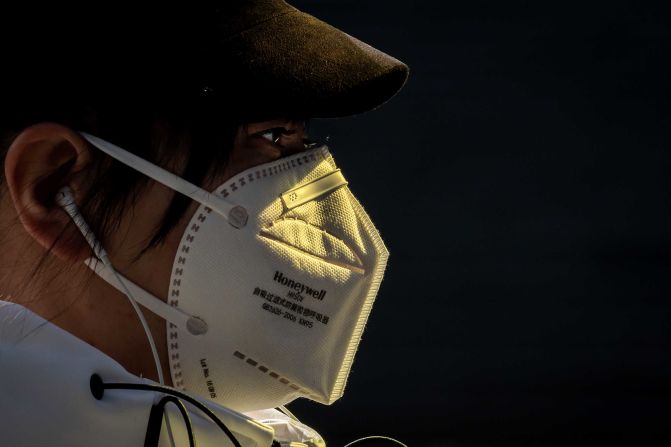

The novel coronavirus has since exploded into a global pandemic, infecting more than 3.5 millionpeople globally and killing more than251,000.In Hong Kong, there have been more than1,040casesso far – relatively low due to months of stringent quarantine measures and closed borders.

But the pandemic dealt a second blow to a population already devastated by six months of violent unrest – and now, experts warn it could culminate in a mental health crisis.

Yau certainly feels the toll. “I feel fatigued, both physically and mentally,” he said. “After you go to the protests, you just feel tired. Right now, we don’t have protests so we don’t have that physical stress, but on the mental side, it’s still the same … I feel very hopeless.”

It’s a common sentiment: In a survey by Hong Kong University between March and April, more than 40% of respondents showed symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or any combination of the three.

These numbers may be even higher, in reality, due to under-reporting; many Hong Kongers are reluctant to talk openly about or disclose mental illness due to deep-rooted social stigma and insufficient mental health education.

Activists and educators have been working for years to break down this stigma, but they say the fight has taken on a new urgency, as people buckle under the weight of two back-to-back crises with no immediate relief in sight.

‘We’re not starting from zero’

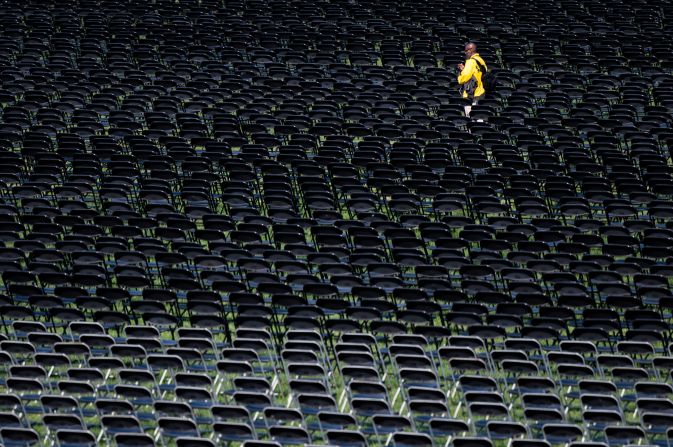

The 2019 social unrest was violent in a way few Hong Kong residents had seen in the normally safe, orderly city.

Nearly every weekend, police and protesters faced off in heated clashes, leaving the streets littered with tear gas canisters, rubber bullets and smashed petrol bombs.

More than 2,600 people were hospitalized from June to December and protesters on the front lines said it felt like being in a war zone.

But the conflicts also left deep wounds in the city’s mental health. It was impossible to escape or ignore: the unrest shuttered businesses, disrupted daily life, and even turned family members against each other.

A study published in January found that almost 2 million people, about a third of Hong Kong’s adult population, experienced PTSD symptoms during this period, with another 590,000suffering probable depression.

PTSD is an anxiety disorder that manifests after a traumatic experience and can cause sleeplessness, flashbacks, emotional withdrawal and traumatic nightmares.

If resilience and our ability to deal with difficult events was measured in buckets, Hong Kongers’ buckets were overflowing even before the pandemic began, said Hannah Reidy, a clinical psychologist and CEO of mental health organization Mind HK.

Millions worldwide are now struggling with the mental health effects of isolation, income loss, and more – but it’s taking a double toll on Hong Kongers because “their buckets were full anyway – we’re not starting from zero,” Reidy said.

The big stressors

One of the biggest and most common sources of stress has been the financial impact of these two crises.

The six months of unrest hit the entertainment, hospitality, and airline industries particularly hard, with travelers and international companies staying away and Hong Kong residents staying home. Now, the pandemic is causing further closures, pay cuts, hiring freezes and layoffs.

“It’s very, very hard to find opportunities, or they pay very little,” said Mark, a 23-year-old photographer and videographer who requested a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “I’m working full time but there have been pay cuts and no paid leave.”

Since the pandemic started, he’s lost about half his income, he said – and with bills and rent piling up, he’s worried. “How can anyone be expected to pay the same amount of bills when you’re not being paid the same salary?” he said.

Karman Leung hears the same anxieties on a daily basis. As the CEO of Samaritans, a Hong Kong-based 24-hour suicide prevention hotline, she’s noticed a shift in the issues people call about.

“There are a lot more people saying they will have to apply for social welfare and aid,” she said. “We have people who have lost their jobs, they mention that they’ve been struggling since last year – for example, they managed to keep their jobs last year but eventually still lost their jobs in the early months of this year.”

She’s also noticed other common stressors, such as the resurfacing trauma of the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic. SARS killed more than 280 people in Hong Kong – the highest proportion of death per capita of any territory in the world.

“We have people who have been through SARS, and feel traumatized by the memories coming back,” said Leung. “Some of them have had family members who were sick during SARS, and they can’t help but worry what will happen this time.”

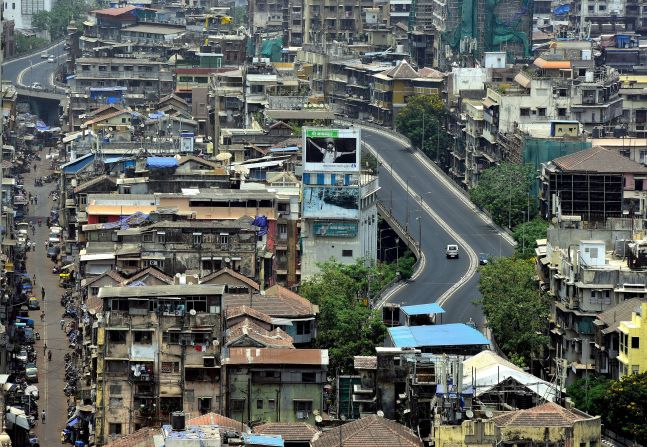

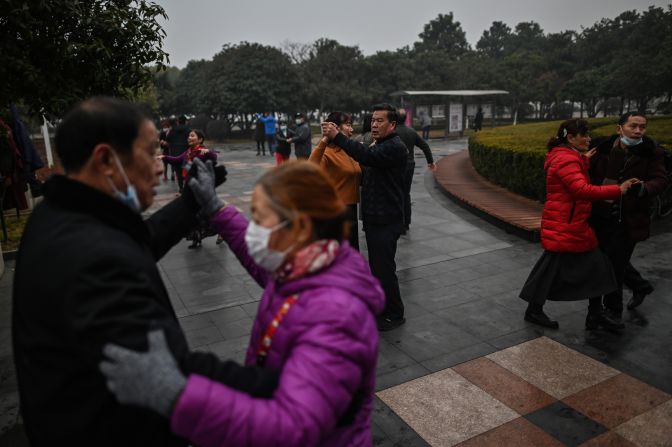

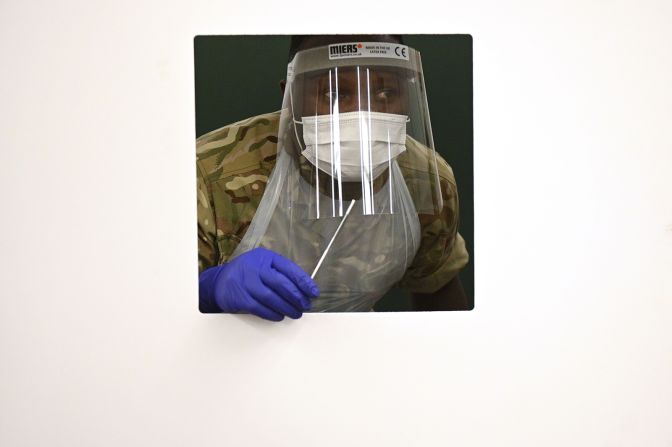

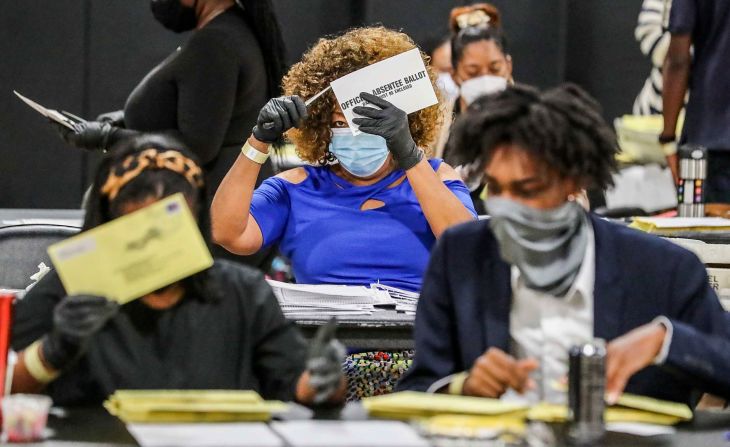

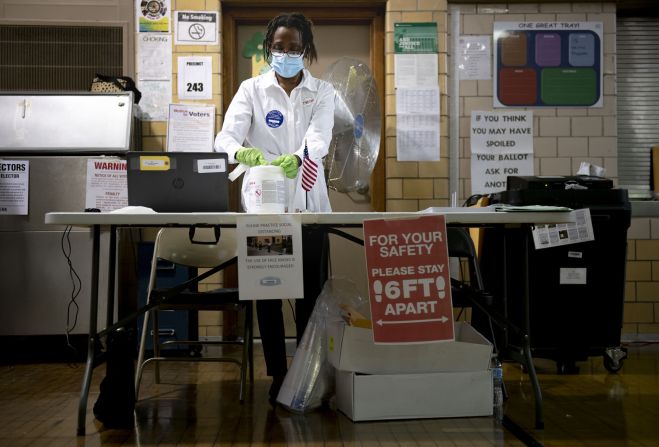

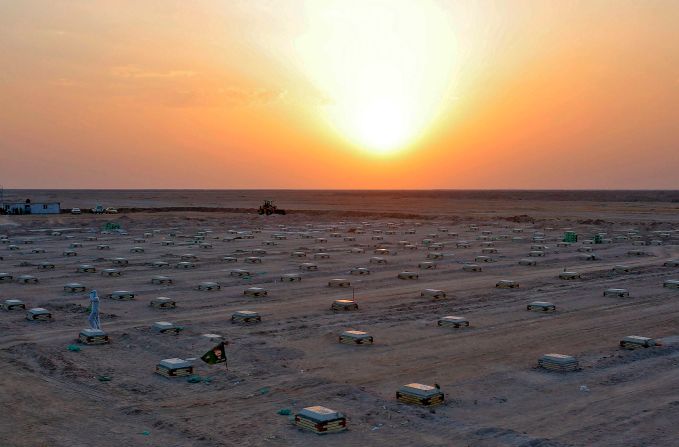

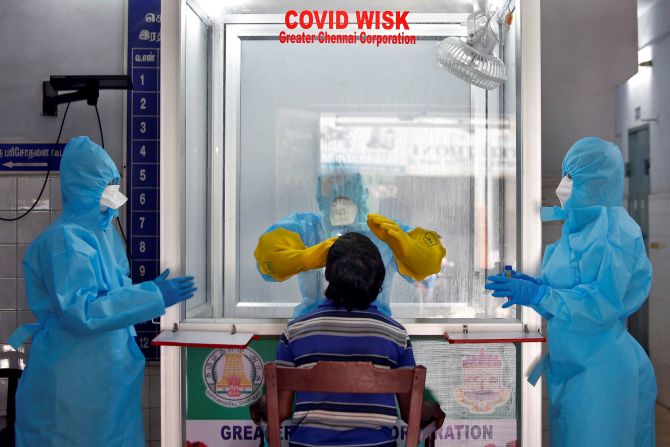

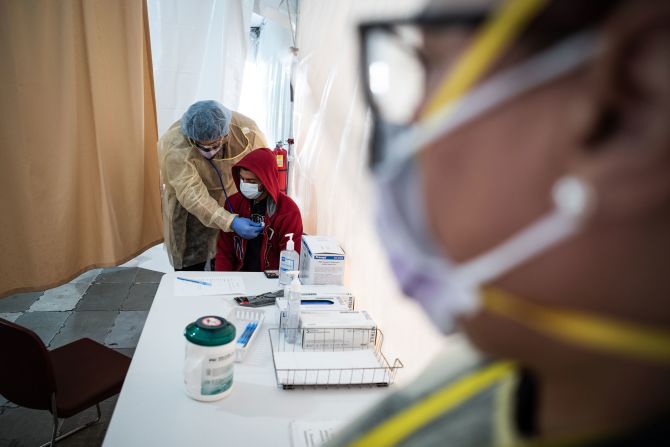

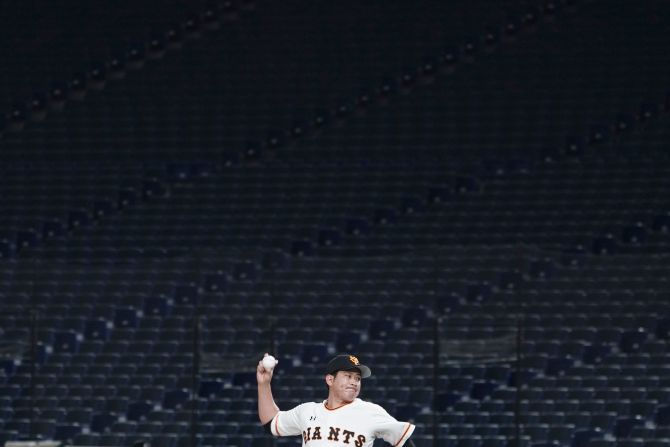

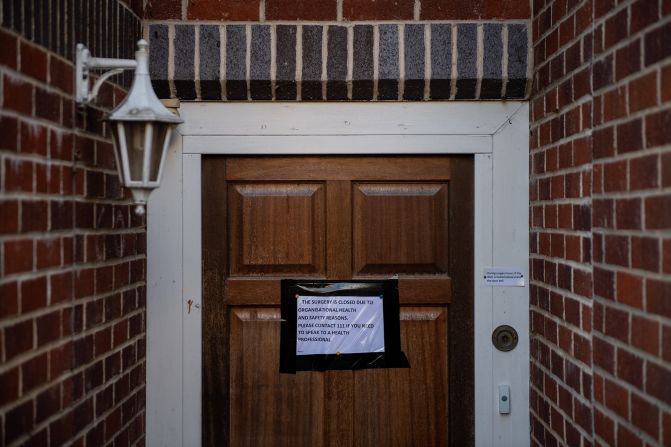

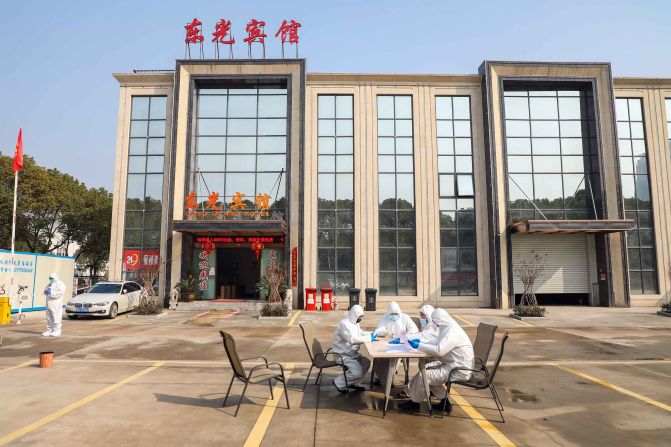

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

Samaritans gets callers ranging from high school students to elderly residents in nursing homes, she added. People in all age groups are struggling from symptoms of mood disorders like depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

Young people may not have as many financial burdens as working adults, but they are also juggling the stress of exams and an uncertain future in this hyper-political climate. And with people social distancing and working from home, many feel isolated and cut off from their normal support networks.

Connecting all these loose threads is the deep sense of fatigue – a mental and emotional exhaustion that saps your energy even if you’re just sitting at home. Hong Kongers have been glued to the news, focused on economic survival, and worried about their health and physical safety for more than 10 months without reprieve.

“We can tell people are more tired and exhausted,” said Leung. “When they talk about how they’re doing mentally now, we talk about what they’re going through, and whenever they mention last year, it’s quite obvious that they’ve been stretched for a long period of time.”

These problems aren’t new

Hong Kong’s mental health problems started long before the protests.

It’s a city with skyrocketing home costs, strong emphasis on academic achievement and long working hours. By 2018, studies showed that at least one in six residents had a common mental disorder, such as anxiety, depression and psychotic disorders, according to Sherry Kit Wa Chan, clinical assistant professor in psychiatry at the University of Hong Kong.

But for years, this issue was swept under the rug, with mental illness treated as a taboo topic. It wasn’t until 2015, when a string of student suicides stunned the city, that people began demanding more change and open conversation.

“(There was) no education about it at school,” said Yau, the banking analyst. “It wasn’t until you figured out that you had symptoms that (teachers) try to take you to see a doctor … Only when students collapse, do they realize that these children face too much pressure.”

The student suicides ushered in a citywide discussion on the incredible pressure placed on students to succeed. Almost as soon as their kids are born, parents begin vying for coveted spots in top kindergartens, and cram their children’s schedules full of extra-curriculars. The overcrowded, overqualified competition also means graduates are finding fewer job opportunities and stagnated upward mobility – exacerbating the mental strain this generation faces.

But a lack of general education on mental health and illness means most people hold misconceptions that are difficult to break down – for instance, the notion that it’s a choice or a matter of willpower.

“People think there’s no in-between, you’re either mentally well or (ill),” said Reidy. “(They think) there’s a dichotomy instead of a spectrum. Mental illness is seen as a sign of weakness.”

It’s also partly a cultural issue, Leung added – a reluctance to burden others with your struggles, and a mentality that you should endure hardship with a good attitude. These beliefs often prevent people from seeking help; most of the people who call Samaritans feel unable to tell anyone else about their difficulties for fear of ostracism or discrimination, she said.

But there are small signs this may be changing, despite – or because of – the city’s fragile state right now.

The government’s 2020 budget includes resources allocated to “support people suffering from mental distress,” according to the budget site, though no specific figure was announced.

“There’s no doubt the past few months have been difficult for Hong Kong’s mental health, we’re heading toward an increased incidence of mental illness or health issues,” said Reidy. “But that doesn’t mean they aren’t willing to talk about it more.”

Mind HK’s website is seeing more visitors than ever. There is higher demand for webinars and online mental health resources. And people feel more comfortable talking about the ways they’re struggling, perhaps because the entire city – the whole world, really – is going through the same thing.

“I think it’s that feeling of it being a shared experience now, it’s acceptable to feel stressed and anxious because that’s how everyone is feeling,” said Reidy. She doesn’t know whether this openness will continue after the pandemic ends, and there’s still a lack of general public knowledge regarding mental health – “but at least they’re asking now.”

“That wasn’t happening before because of the stigma,” she added. “The appetite is there. Now it’s on everybody to keep the conversation going and keep pushing.”