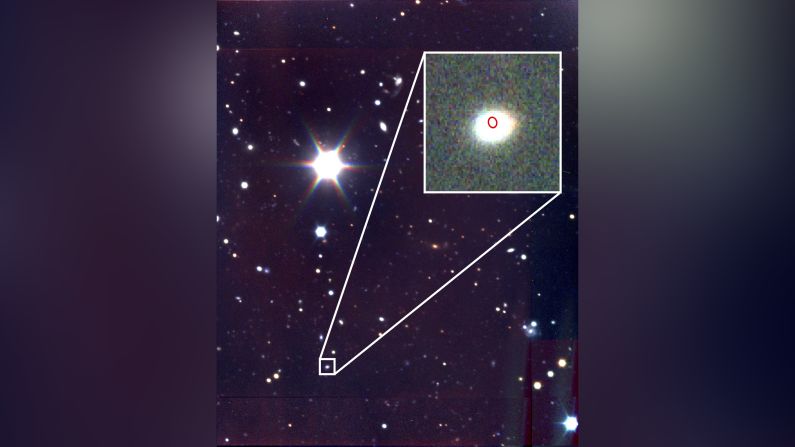

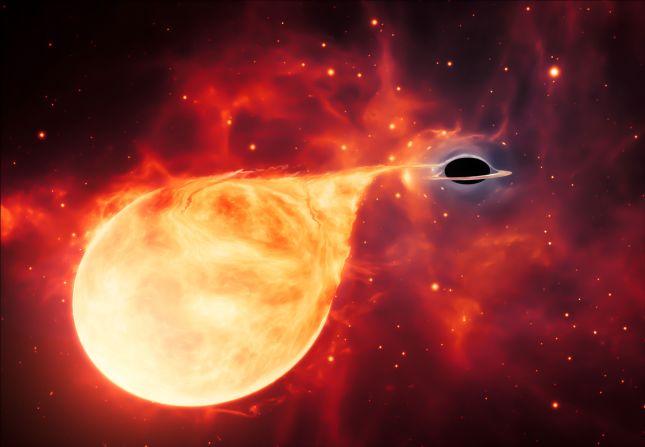

A red giant star strayed too close to a supermassive black hole in a galaxy 250 million light-years away. Instead of being gobbled up, the star survived – but it’s not in an ideal situation, either. In a drawn-out process of destruction that leads to a kind of renewal, the star will transform into a planet.

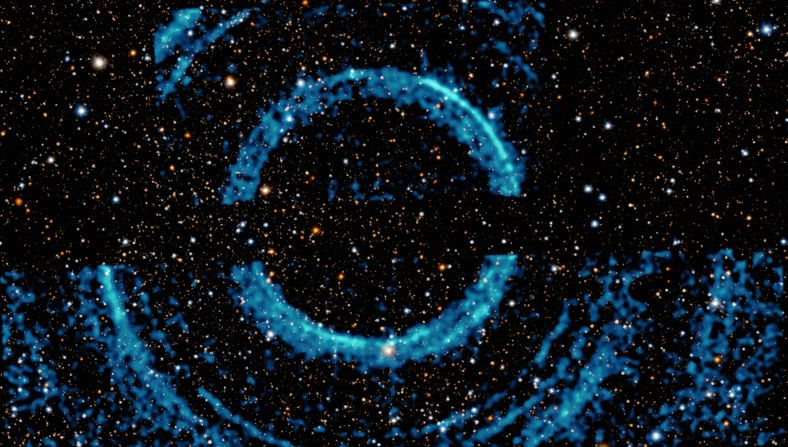

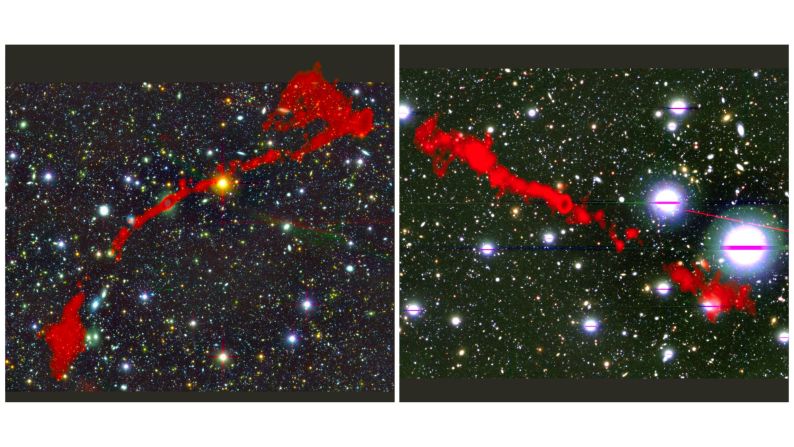

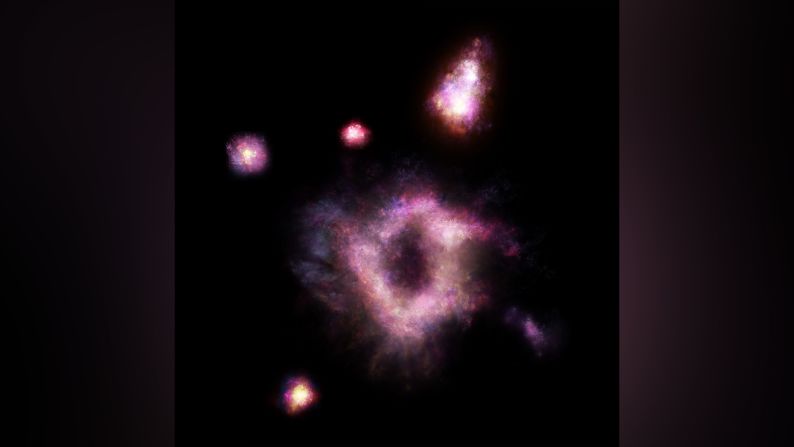

Observations by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton, both of which launched in 1999, captured this stellar story by detecting X-ray data.

The supermassive black hole is at the heart of a galaxy called GSN 069. It’s on the smaller side, as far as the range for supermassive black holes go, and only about 400,000 times the mass of our sun.

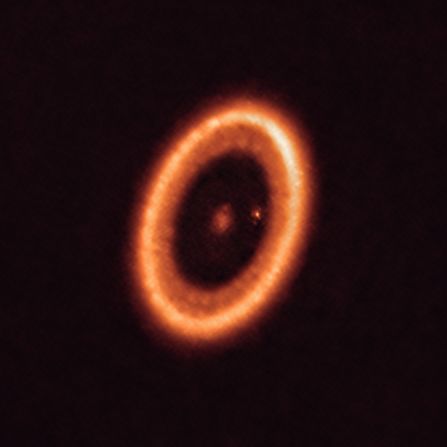

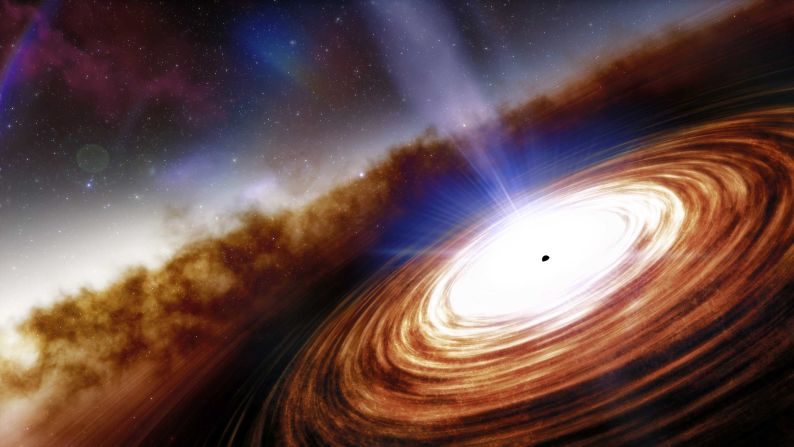

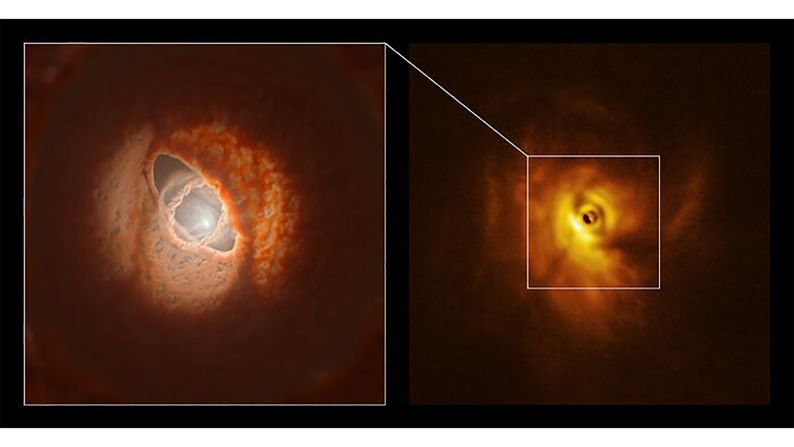

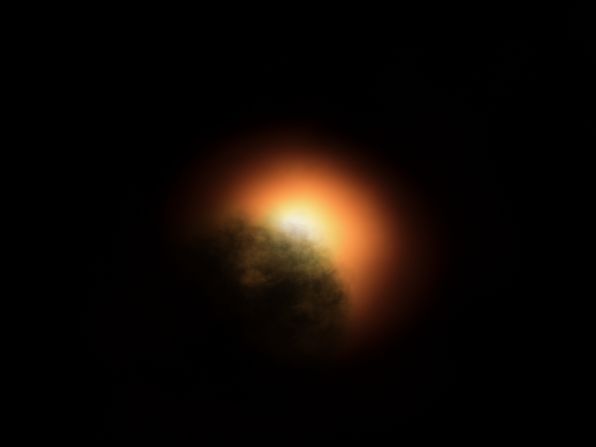

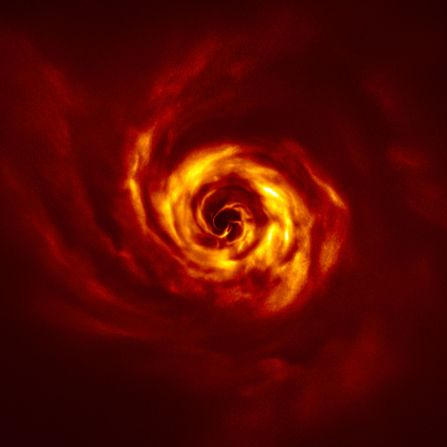

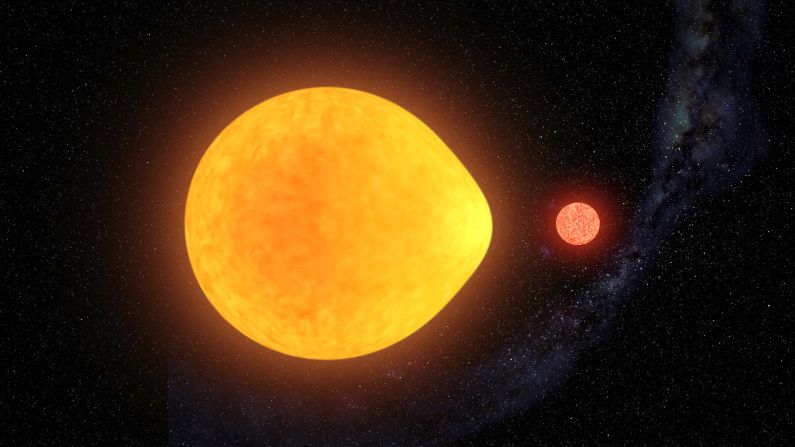

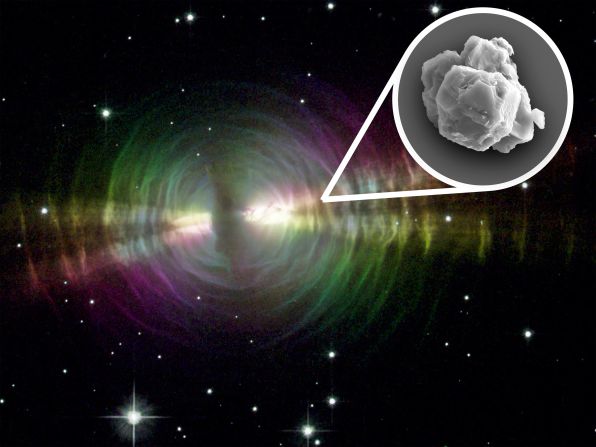

When the black hole’s gravity seized the red giant it stripped off the star’s outer hydrogen layers. Only the star’s core, known as a white dwarf, remained.

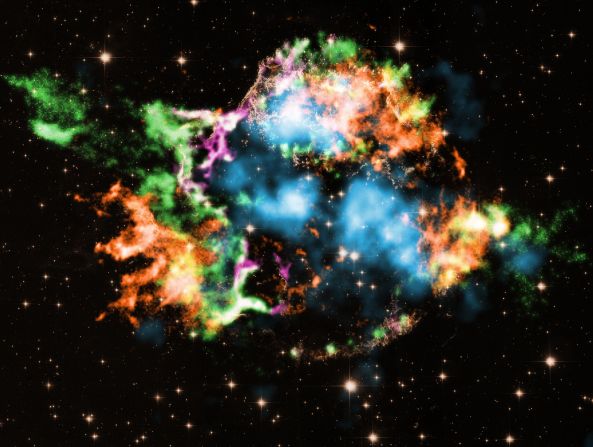

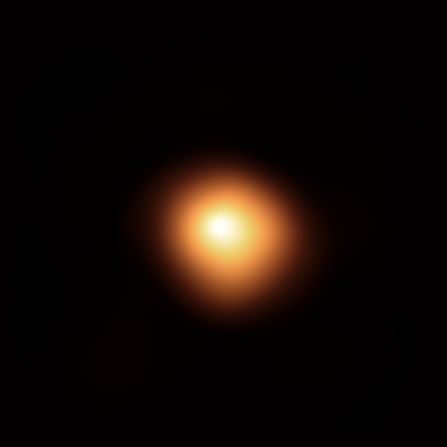

When a sun-like star reaches the end of its life and burns through all of its fuel, it puffs up to form a red giant and blasts out about half of its mass. A blazing hot white dwarf is left behind. But the black hole forced this stellar evolution.

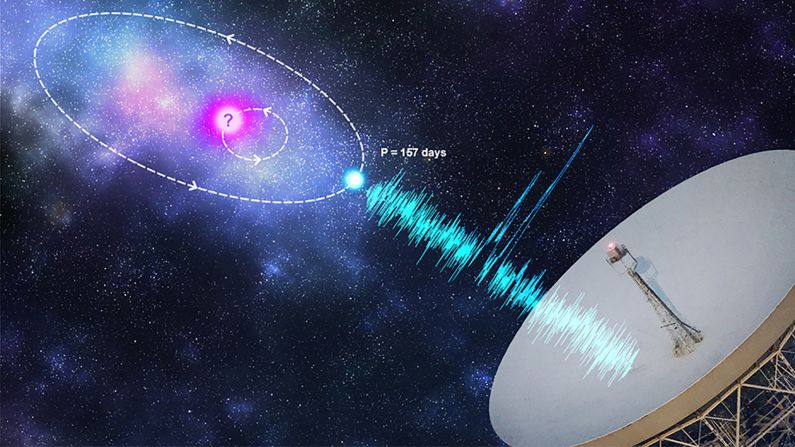

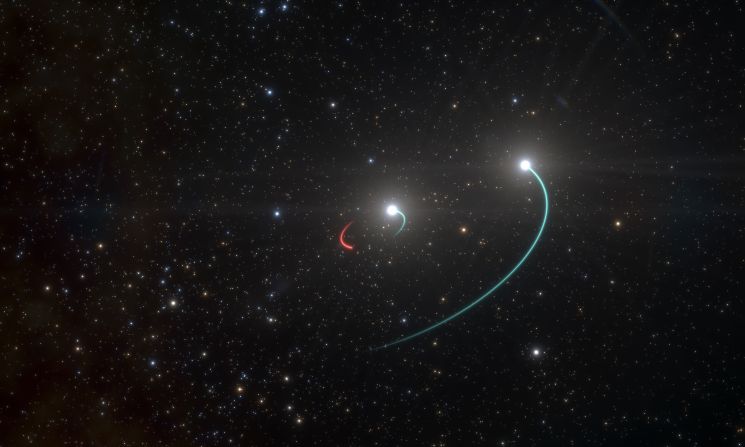

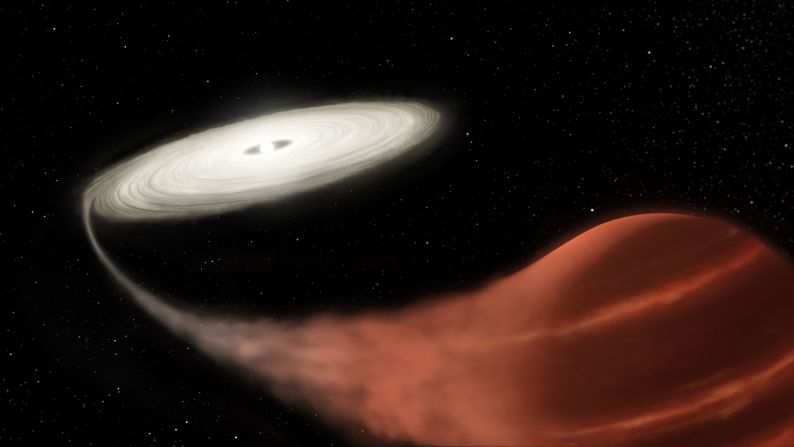

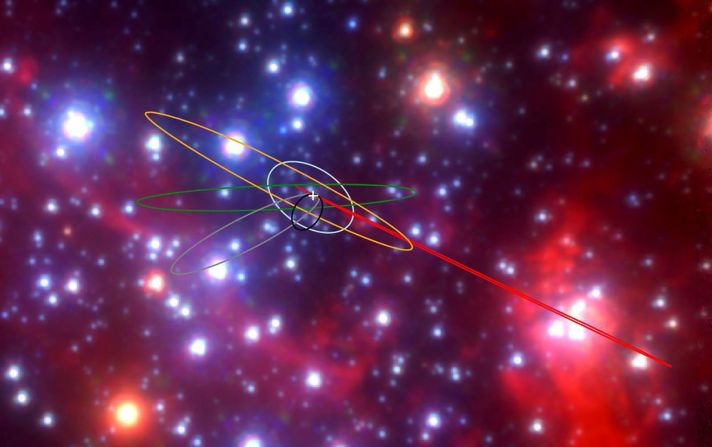

“In my interpretation of the X-ray data, the white dwarf survived, but it did not escape,” said Andrew King, study author and professor of theoretical astrophysics at the University of Leicester, in a statement. “It is now caught in an elliptical orbit around the black hole, making one trip around about once every nine hours.”

The study published last month in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

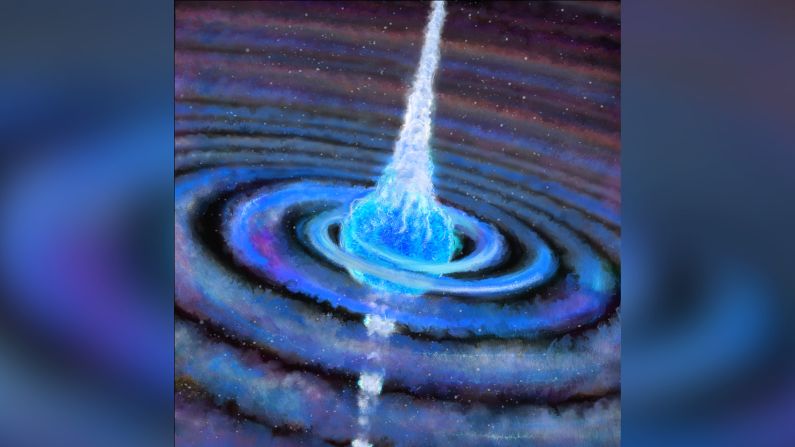

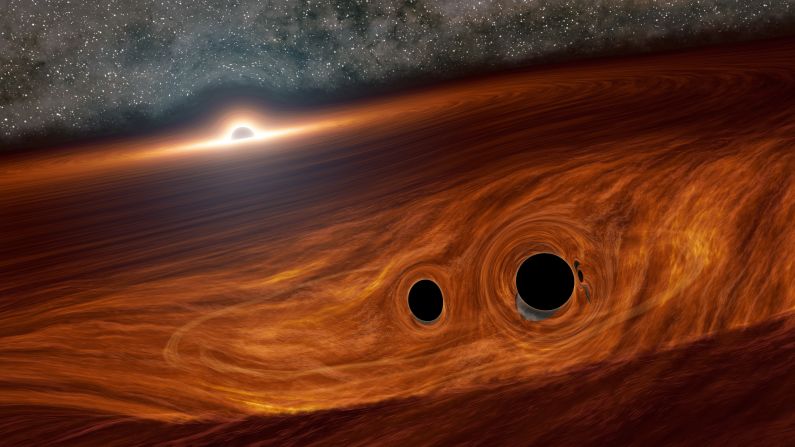

The black hole is continuing to slowly eat away at the star’s core, tearing off material during the star’s closest approach during its orbit. When the material that’s ripped off the star enters the disk of material whirling around the black hole, it releases X-rays.

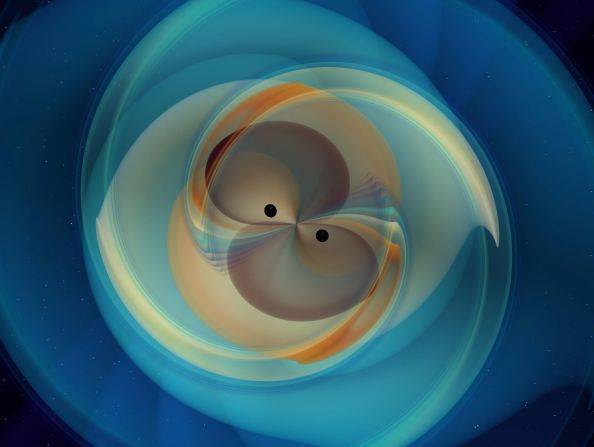

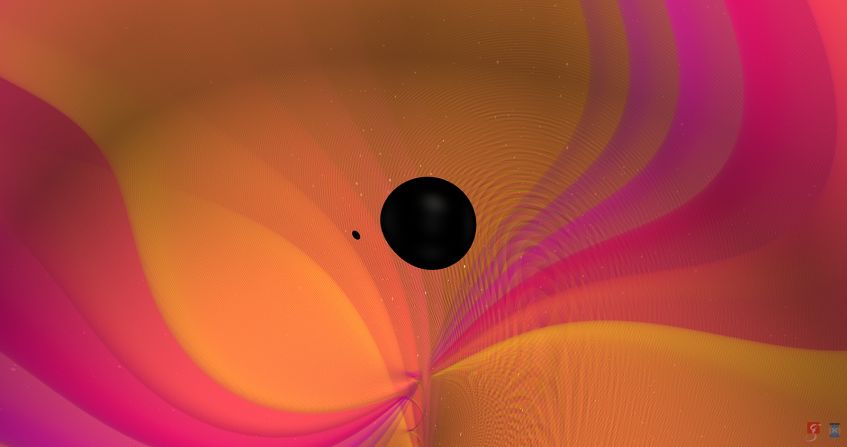

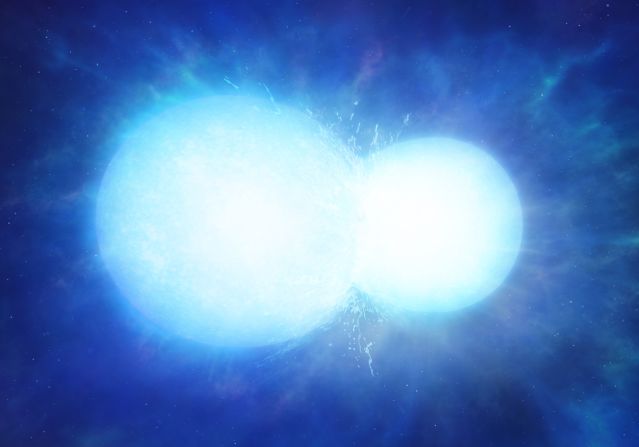

King also believed that the white dwarf and black hole pair will release gravitational waves, or ripples in space time, when they come close together.

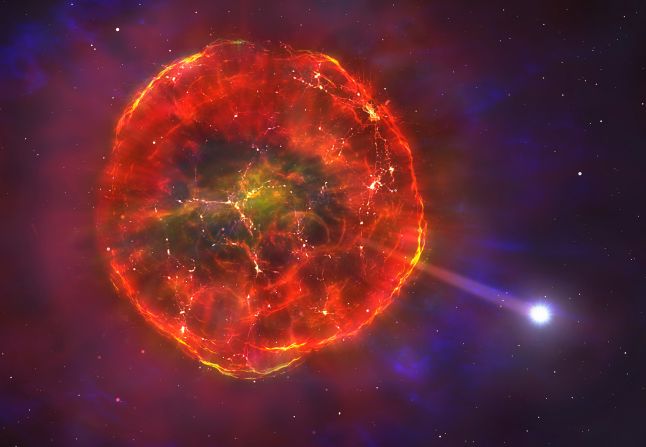

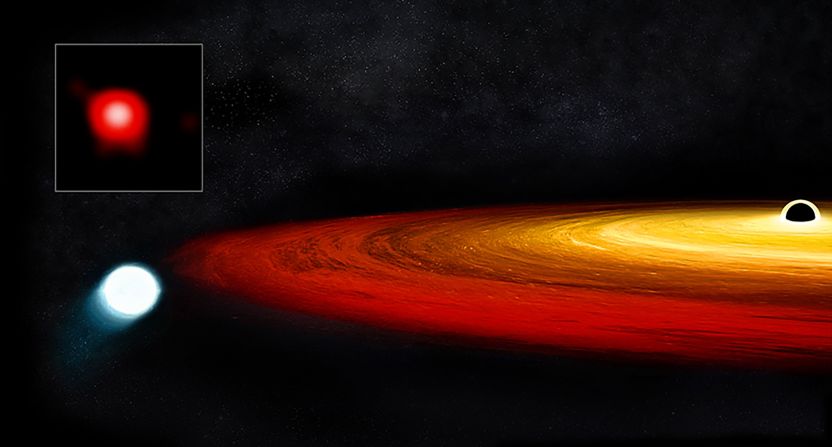

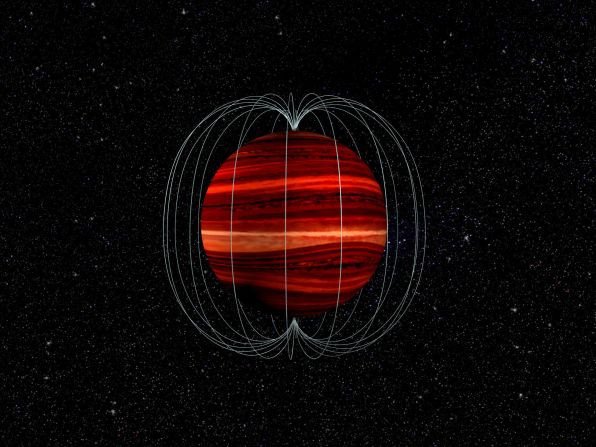

“It will try hard to get away, but there is no escape,” King said. “The black hole will eat it more and more slowly, but never stop. In principle, this loss of mass would continue until and even after the white dwarf dwindled down to the mass of Jupiter, in about a trillion years. This would be a remarkably slow and convoluted way for the universe to make a planet!”

This tale of star survival in the face of a hungry supermassive black hole, albeit a grim one, is rare. Most stars are shredded by their encounters. Or, if the supermassive black hole is larger than this one, they simply swallow the star.

“In astronomical terms, this event is only visible to our current telescopes for a short time — about 2,000 years,” King said. “So unless we were extraordinarily lucky to have caught this one, there may be many more that we are missing. Such encounters could be one of the main ways for black holes the size of the one in GSN 069 to grow.”

The white dwarf is likely only two-tenths the mass of our sun and comprised of helium since the hydrogen has been stripped away.

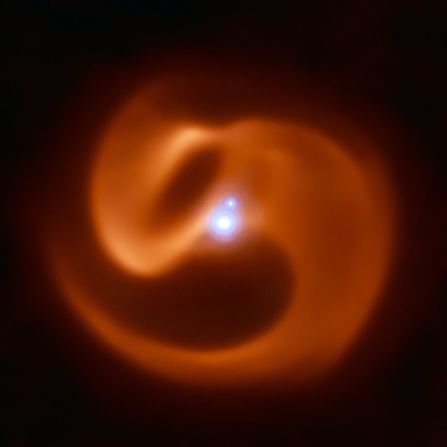

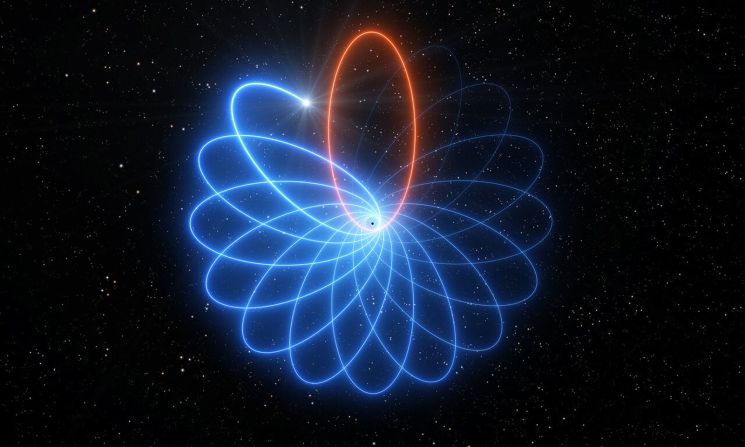

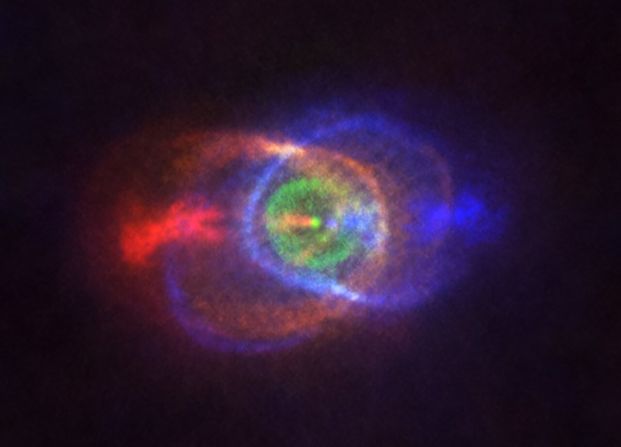

And because the white dwarf is so close to the black hole, Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity suggests that the direction of the orbit’s axis will rotate with time, causing a repeating wobble and a pattern that looks like a rosette.

The same is true in a recent study of a star seen in a rosette orbit around the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

“It’s remarkable to think that the orbit, mass and composition of a tiny star 250 million light-years away could be inferred,” King said.

Because white dwarf stars actually expand as they lose mass, the orbit of the star will actually expand after each rotation. This will cause the white dwarf star to spiral further away from the black hole, slowing the amount of mass lost from the star.

Eventually, “the white dwarf mass decreases to about that of Jupiter, becoming a planet,” King wrote in a blog post for the Chandra Observatory site. “As the planet loses mass its radius then shrinks, and gravitational radiation very slowly pulls it back in, until the black hole finally swallows the vestige that is left.”