The morning after Ian Lahiffe returned to Beijing, he found a surveillance camera being mounted on the wall outside his apartment door. Its lens was pointing right at him.

After a trip to southern China, the 34-year-old Irish expat and his family were starting their two-week home quarantine, a mandatory measure enforced by the Beijing government to stop the spread of the novel coronavirus.

He said he opened the door as the camera was being installed, without warning.

“(Having a camera outside your door is) an incredible erosion of privacy,” said Lahiffe. “It just seems to be a massive data grab. And I don’t know how much of it is actually legal.”

Although there is no official announcement stating that cameras must be fixed outside the homes of people under quarantine, it has been happening in some cities across China since at least February, according to three people who recounted their experience with the cameras to CNN, as well as social media posts and government statements.

China currently has no specific national law to regulate the use of surveillance cameras, but the devices are already a regular part of public life: they’re often there watching when people cross the street, enter a shopping mall, dine in a restaurant, board a bus or even sit in a school classroom.

More than 20 million cameras had been installed across China as of 2017, according to state broadcaster CCTV. But other sources suggest a much higher number. According to a report from IHS Markit Technology, now a part of Informa Tech, China had 349 million surveillance cameras installed as of 2018, nearly five times the number of cameras in the United States.

China also has eight of the world’s 10 most surveilled cities based on the number of cameras per 1,000 people, according to UK-based technology research firm Comparitech.

But now the pandemic has brought surveillance cameras closer to people’s private lives: from public spaces in the city right to the front doors of their homes — and in some rare cases, surveillance cameras inside their apartments.

CNN has requested comment from China’s National Health Commission. The Ministry of Public Security did not accept CNN’s faxed requests for comment.

Evolution of tactics

China is already using a digital “health code” system to control people’s movements and decide who should go into quarantine. To enforce home quarantine, local authorities have again resorted to technology — and have been open about the use of surveillance cameras.

A sub-district office of the government in Nanjing, in eastern Jiangsu province, said it had installed cameras outside the doors of people under self-quarantine to monitor them 24 hours a day — a move that “helped save personnel expenditures and increased work efficiency,” according to its February 16 post on Weibo, China’s twitter-like platform.

In Hebei province, the Wuchongan county government in the city of Qianan also said it was using surveillance cameras to monitor residents quarantined at home, according to a statement on its website. In the city of Changchun in northeastern Jilin province, the quarantine cameras in Chaoyang district are powered with artificial intelligence to detect human shapes, the district government said on its website.

In the eastern city of Hangzhou, China Unicom, a state-owned telecom operator, helped the local governments install 238 cameras to monitor home-quarantined residents as of February 8, the company said in a Weibo post.

On Weibo, some people posted photos of cameras they said were newly put up outside their doors, as they went into home quarantine in Beijing, Shenzhen, Nanjing and Changzhou, among other cities.

Some appeared to accept the surveillance, although it remains unclear how much criticism against the measure is tolerated on the country’s closely monitored and censored internet. A Weibo user, who went into home quarantine after returning to Beijing from Hubei province, said she was told in advance by her neighborhood committee that a camera and an alarm would be installed on her front door. “(I) fully respect and understand the arrangement,” she wrote.

Another Beijing resident said he did not think the camera was necessary, “but since it is a standard requirement, (I’m) happy to accept it,” wrote a person who identified himself as Tian Zengjun, a lawyer in Beijing.

Others, worried about the virus’ spread in their communities, called for local authorities to install surveillance cameras to ensure people obey quarantine rules.

Jason Lau, a privacy expert and professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, said people across China had grown accustomed to prevalent surveillance long before the coronavirus.

“In China, people probably already assume that the government has access to a lot of their data anyway. If they think the measures are going to keep them safe, keep the community safe and are in the best interest of the public, they may not worry too much about it,” he said.

Cameras inside homes

Some people say cameras have even been placed inside their homes.

William Zhou, a public servant, returned to the city of Changzhou, in eastern Jiangsu province, from his native Anhui province in late February. The next day, he said a community worker and a police officer came to his apartment and set up a camera pointing at his front door – from a cabinet wall inside his home.

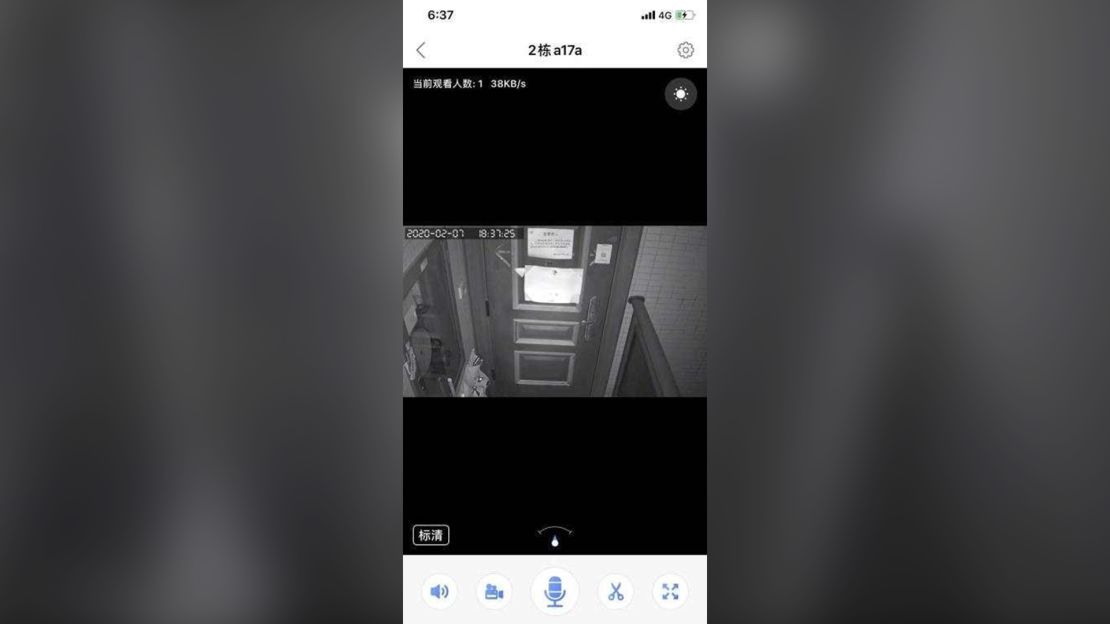

Zhou said he did not like the idea. He asked the community worker what the camera would record and the community worker showed him the footage on his smartphone.

“I was standing in my living room and the camera captured me clearly in its frame,” said Zhou, who asked to use a pseudonym for fear of repercussions.

Zhou was furious. He asked why the camera couldn’t be placed outside instead, but the police officer told him it might get vandalized. In the end, he said the camera stayed on the cabinet despite his strong protest.

On that evening, Zhou said he called the mayor’s hotline and the local epidemic control command center to complain. Two days later, two local government officials turned up at his door, asking him to understand and cooperate with the government’s epidemic control efforts. They also told him the camera would only take still images when his door moved and wouldn’t record any video or audio.

But Zhou remained unconvinced.

“(The camera) had a huge impact on me psychologically,” he said. “I tried not to make phone calls, fearing the camera would record my conversations by any chance. I couldn’t stop worrying even when I went to sleep, after I closed the bedroom door.”

Zhou said he would have been fine with having the camera placed outside his front door, because he wouldn’t open the door to go out anyway.

“Installing it inside my home is a huge invasion of my privacy,” he said.

Zhou said two other residents who were under quarantine in his residential compound told him they also had cameras installed inside their homes.

The epidemic control command center of the district Zhou lives in confirmed to CNN the use of cameras to enforce home quarantine, but declined to give further details.

In the eastern city of Nanjing, the Chunxi sub-district government posted photos on Weibo showing how authorities were using cameras to ensure quarantine. One photo showed a camera standing on a cabinet inside an apartment. Another showed a screenshot of footage of four cameras, some of which appeared to have been shot from inside people’s homes.

The Chuxi sub-district government declined to comment. The epidemic control command center in the district said the installation of cameras was not a mandatory policy, and some sub-district governments have chosen to adopt the measure themselves.

How do the cameras work?

There is no official tally on the number of cameras installed to enforce home quarantine across China. But the Chaoyang district government in Jilin, a city of four million people, said in a statement that it had installed 500 cameras as of February 8.

Around the world, governments have adopted less intrusive technologies to track whether a person leaves their apartment. In Hong Kong, for example, all international arrivals undergoing a two-week home quarantine must wear an electronic bracelet, which connects to a smartphone app that alerts authorities if they stray from their apartments or hotel rooms. South Korea uses an app that tracks locations with GPS and sends alerts when people leave quarantine. Last month, Poland launched an app that allows people under quarantine to send selfies to let authorities know they’re staying home.

Even in Beijing not everyone in home quarantine has a camera outside their home. Two residents, who recently returned to the city from Wuhan, said they had a magnetic alarm installed to their apartment doors, which would notify community workers if they stepped outside. CNN has reached out to Beijing authorities for comment.

Lahiffe, the Irish expat who lives in Beijing, believes the footage from his camera is being monitored by the community workers at his residential compound, who are charged with making sure he stays home and doesn’t have visitors – all from a smartphone.

“The guy’s phone has an app which (shows) all the doors,” Lahiffe said of one of the community workers who had come to install the camera. “You can see all the doors of the different cameras that have been installed,” he said, adding that he saw more than 30 doors on the app, all from his residential complex which he says is lived in by “mostly foreigners.”

In China, every urban residential community is managed by a neighborhood committee, a communist legacy from the Mao era that has now become the foundation of a “grid management” system of social control supported by high tech and big data. Officially, these are self-governing bodies that manage and educate residents. But they also serve as the governments’ eyes and ears at the grassroots level, helping to maintain stability by watching over millions of residents nationwide and reporting suspicious activities.

Since the outbreak, community workers have been given great leeway and tasked with epidemic control in residential compounds, enforcing home quarantine, as well as helping quarantined residents with basic needs, such as delivering food and groceries to their doors and taking out their trash.

Whenever Lina Ali, a Scandinavian expat living in the southern city of Guangzhou, opened her front door to receive food deliveries, she said a bright light shone from the camera that was trained on her apartment door while she was in quarantine.

She said her apartment building’s property management staff came to install a surveillance camera outside her front door on the first day of her home quarantine earlier this month.

“I hated when the camera would shine a bright light, they told us that it connects to the police station,” said Ali. CNN agreed to refer to her with a pseudonym to protect her safety. “It made me feel like I truly was a prisoner in my own home.”

CNN has reached out to Guangzhou authorities for comment.

In Shenzhen, the cameras used to monitor quarantined residents in one district were connected to the smartphones of police officers and community workers, according to a report on the district government’s website.

If someone breached their quarantine, the report said,”police and community workers will receive an alert immediately notifying them something is wrong.”

Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch, said there was a wide range of measures governments can take to protect public health in the pandemic, but “they don’t necessarily have to blanket society with surveillance devices.”

“If you look at China’s surveillance measures during the coronavirus outbreak, from the development of health codes to installation of surveillance cameras to enforce quarantine, we’re seeing an increasingly intrusive use of surveillance technologies that were previously only seen in particularly repressed regions, like Xinjiang,” she said, referring to the far western region home to China’s Uyghur minority.

“The surveillance measures being implemented during Covid-19, are unfortunately — if not pushed back — going to live with us for a very long time.”

The legal stance

China currently has no specific national law to regulate the use of surveillance cameras in public spaces. The Ministry of Public Security released a draft regulation on security cameras in 2016, but the ordinance is still waiting to be approved by the country’s national legislature. In recent years, some local governments have issued their own regulations on the cameras.

Tong Zongjin, a lawyer based in Beijing, said installing cameras outside a person’s front door has always been in a legal gray area.

“The area outside a person’s front door is not part of their private residence and is considered a communal space. But the camera can be monitoring something personal, such as when the individual leaves and comes home,” he said.

Adding to the complexity of the issue is that these cameras are installed by authorities during a public health emergency for epidemic control purposes, so an individual’s privacy has to be balanced against public interest and safety, Tong said.

On February 4, the Cyberspace Administration of China issued a directive, calling on regional cyberspace authorities to “actively make use of big data, including personal information, to support epidemic prevention and control work,” while protecting people’s personal information.

The directive bans the collecting of personal data for epidemic control without consent from organizations that have not received the approval from health authorities under China’s cabinet, the State Council.

It also said the collection of personal information should be limited to “key groups” such as confirmed or suspected Covid-19 patients and their close contacts, and that the information collected should not be used for other purposes, or be made public without consent. Organizations that collect personal information should adopt strict measures to protect data from being stolen or leaked, the document said.

Lau, the privacy expert, said under Chinese law, organizations with the authority to collect and report personal information concerning public health emergencies include national and regional health authorities, medical institutions, disease prevention and control authorities, as well as local authorities such as townships and resident committees authorized by the government and emergency command headquarters.

“Of course, the government will try to collect as much data as they can to help stop the spread of the virus,” he said. But the government needs to consider if the collection of data is appropriate, necessary and proportionate, and assess if there are other less privacy intrusive methods to do the same thing, he added.

A new era of digital surveillance?

Earlier this month, over 100 rights and privacy organizations around the globe issued a joint statement to call on governments to ensure the use of digital technologies to track and monitor citizens during the pandemic is carried out in line with human rights.

“States’ efforts to contain the virus must not be used as a cover to usher in a new era of greatly expanded systems of invasive digital surveillance,” the statement said.

“Technology can and should play an important role during this effort to save lives, such as to spread public health messages and increase access to health care. However, an increase in state digital surveillance powers, such as obtaining access to mobile phone location data, threatens privacy, freedom of expression and freedom of association, in ways that could violate rights and degrade trust in public authorities – undermining the effectiveness of any public health response,” it said.

For now, it appears that the surveillance cameras on people’s front doors are not there to stay. After Ali and Zhou finished their quarantine, they said the cameras were taken down.

The community workers told Zhou he could keep the camera for free. But Zhou was so furious about having to live under its gaze for two weeks that he said he took out a hammer and smashed the device in front of the community workers.

“If surveillance cameras are placed in public places, there’s no problem – they can monitor and deter unlawful acts. But they shouldn’t appear in our private spaces,” he said.

“I can’t bear the thought that our everyday lives are completely exposed to the government’s scrutiny.”