Rubel, a 28-year-old migrant worker in Singapore, is afraid. The dormitory he and other foreign workers live in has been locked down, and nobody is allowed in or out as government officials scramble to contain the country’s novel coronavirus outbreak.

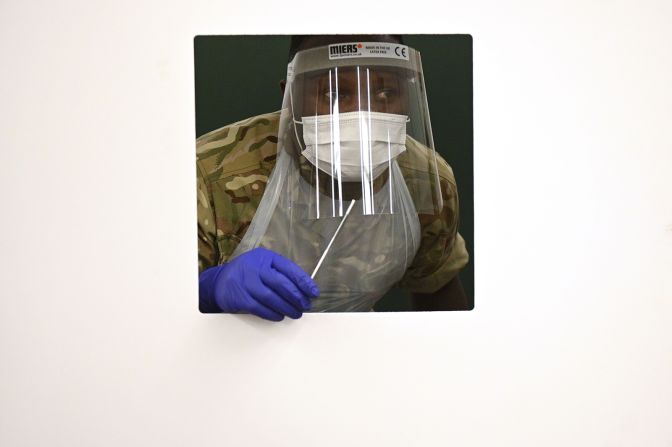

In recent weeks, the Asian city-state has had a dramatic spike in coronavirus infections, with thousands of new cases linked to clusters in foreign worker dormitories. To control the spread, the government has attempted to isolate the dormitories, test workers and move symptomatic patients into quarantine facilities.

But those measures have left hundreds of thousands of workers trapped in their dormitories, living cheek by jowl in cramped conditions that make social distancing near impossible.

Singapore is home to about 1.4 million migrant workers who come largely from South and Southeast Asia. As housekeepers, domestic helpers, construction workers and manual laborers, these migrants are essential to keeping Singapore functioning – but are also some of the lowest paid and most vulnerable people in the city.

Rubel, who goes only by one name, came to Singapore from Bangladesh six years ago to work in construction and earn money for his family. Now, with his health and safety at risk, he’s worried for those who depend on him.

“I’m scared of this coronavirus, because if I catch it I cannot take care of my family,” he said.

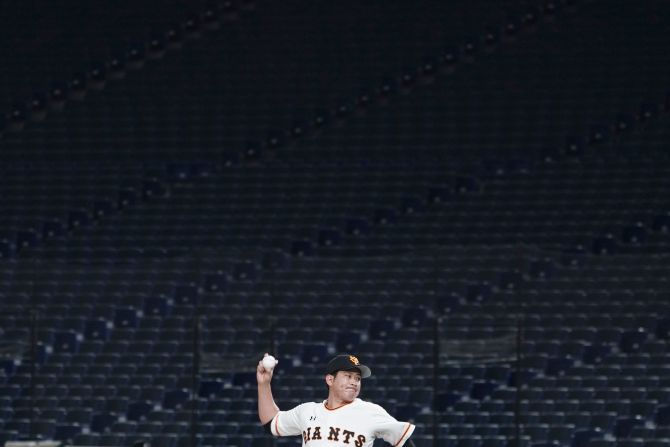

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

In the first three months of the coronavirus pandemic, Singapore was praised for its response and apparent ability to suppress infections without resorting to extreme measures.

Then, in April, the number of cases exploded. Since March 17, Singapore’s total cases grew from 266 to 12,075, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

Even as the number of new cases surged past 1,000 a day, only a dozen or so per day were Singapore citizens of permanent residents; the rest were all migrant workers.

Singapore was built by migrants

Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, is often credited as the visionary who helped transform the city-state into the developed metropolis it is today. But much of Singapore, including iconic sites like the gleaming Marina Bay Sands, was built by imported labor.

Forty years ago, Singapore was less economically developed, with a per-capita income of $4,071 a year, according to the International Labor Organization. Without much land or natural resources, the government instead focused on investing in education, especially in the STEM subjects and vocational training, and creating an export-oriented economy that would obtain wealth through industrialization.

But Singapore had – and still has – a small population, presenting the problem of manpower. So the government turned to foreign labor, and has been doing so ever since. Of the city’s 5.7 million residents today, nearly a quarter are foreign workers, according to government figures.

The ambitious plan to develop Singapore worked – at least, for Singaporeans. The cheap foreign labor fueled growth, raising Singapore’s average income to $56,786 by 2019 and making it one of the wealthiest places in the world in GDP per capita.

But critics say that foreign workers have been sidelined, left mostly living in tougher conditions with fewer benefits or protections than their Singaporean neighbors – meaning when a crisis like Covid-19 arrives, they are the first and hardest hit.

The dormitories were a ‘time bomb’

Singapore started seeing its cases spike around April 4, with 75 new cases – its biggest single-day jump at the time.

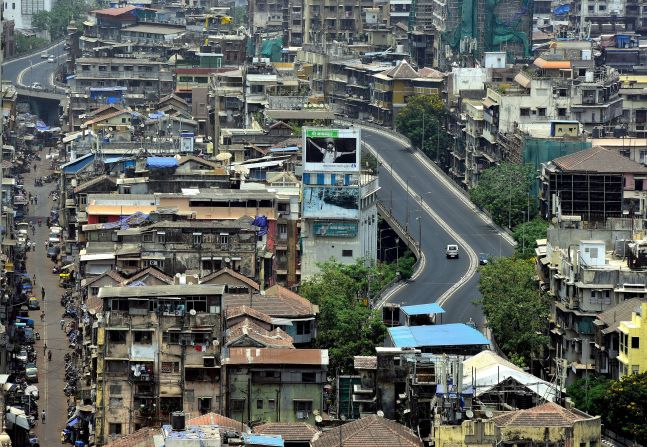

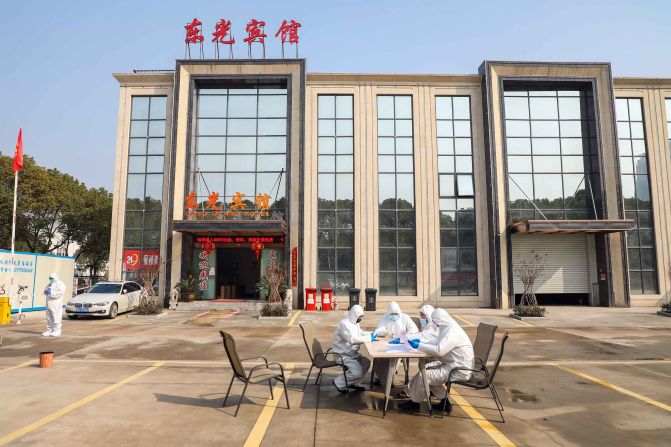

Authorities traced clusters back to the dormitories, which were built specifically for migrant workers and subject to government regulations. About 200,000 workers live in 43 dormitories in Singapore, according to Minister of Manpower Josephine Teo.

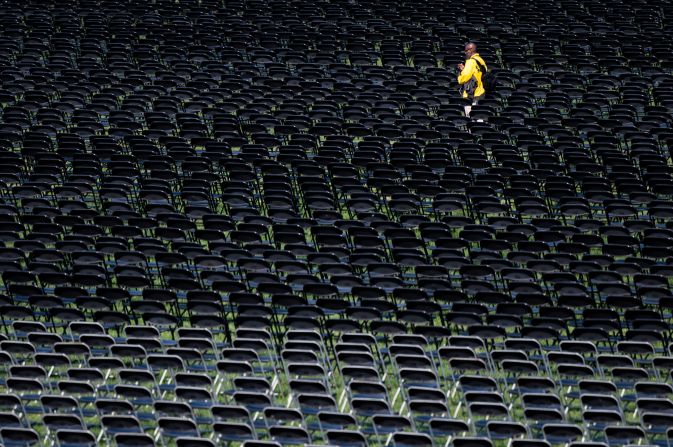

Conditions are usually cramped, with about 10 to 20 workers sharing each room. Government regulations require the rooms provide 4.5 square meters (about 48 square feet) per occupant, meaning the rooms typically range from 45 to 90 square meters (484 to 968 square feet).

Videos sent to CNN from one dormitory show workers lying in a line of bunk beds, where they sleep just a few feet away from each other. The workers, the majority of whom are male, and from less economically developed countries, share toilets, shower stalls, laundry clotheslines, storage spaces, and line up together to receive food.

There’s simply no way to self-isolate or avoid close contact, which may be why the coronavirus spread so fast and far here.

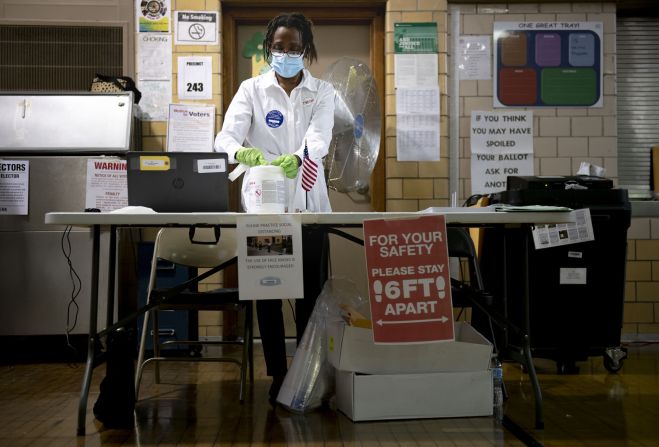

There’s also the fact that authorities seem to have overlooked this risk and didn’t alert the migrant worker community until it was too late, said Alex Au, vice president of the Singaporean non-profit organization Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2).

“When the government of Singapore, governments all over the world, issued safe distancing advice, I think they overlooked the fact that safe distancing cannot be possible when construction workers and other blue-collar workers are housed ten men, 20 men, in a room,” he said. “The failure, I think, to see clearly the risks and to take measures to mitigate the risks, left us with a very bad situation right now.”

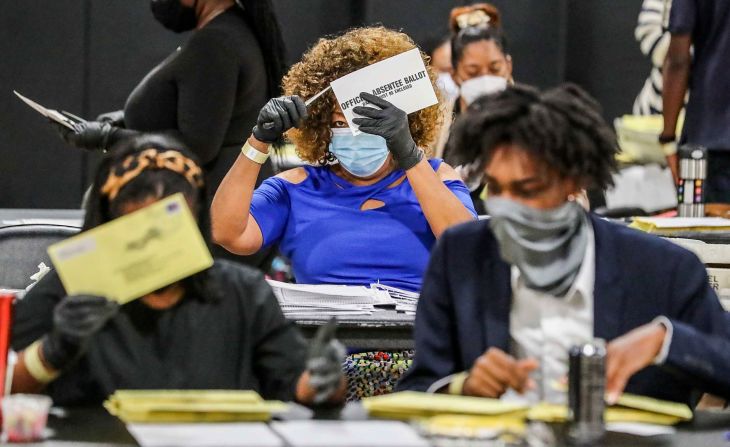

As the number of new daily cases spiked, the government locked down dorms, stepped up hygiene measures inside, and closed recreational common spaces, said the Ministry of Manpower. They also tried to space out residents more, and moved some workers into military camps, floating hotels, and vacant government apartments.

In some dorms, workers say the government measures have reassured residents. Zasim, a 27-year-old worker from Bangladesh, said he had been provided with face masks, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies, soap, and fresh fruit by the government. Authorities had also supplied free WiFi and extra phone cards so Zasim and his dorm-mates could spend their days under lockdown talking to friends and family, he said.

Like Rubel, Zasim’s main concern was the shutdown’s financial impact – but he feels less worried now that the governmenthas said migrant workers should get paid, even if they can’t work, and subsidized employers to make that possible.

Rubel, too, said his living spaces are now clean and the workers are provided with food – but the mood at his dorm remains tense. Even with the additional protective measures, people are still sharing close quarters, and workers worry they may be living among asymptomatic carriers.

“It’s extremely stressful for anybody to be confined in these conditions,” said Desiree Leong, the casework executive at the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics in Singapore. “You’re being kept in there all day, or most of the day. It’s causing a lot of anxiety and stress, a lot of tension.”

Tommy Koh, a Singapore lawyer and former diplomat, was more blunt in a widely-shared Facebook post earlier this month.

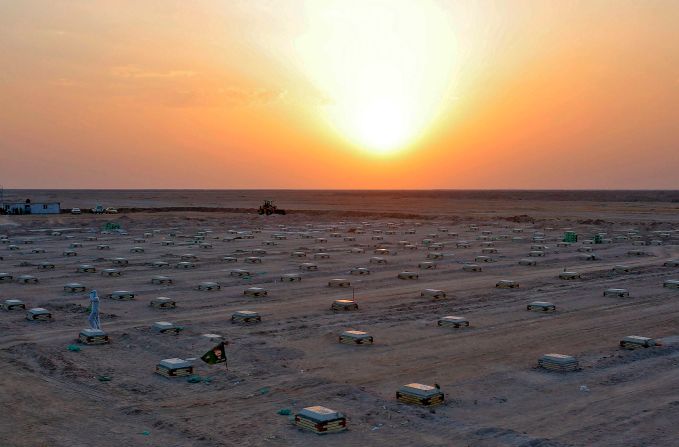

“The dormitories were like a time bomb waiting to explode,” he wrote. “The way Singapore treats its foreign workers is not First World but Third World. The government has allowed their employers to transport them in flat bed trucks with no seats. They stay in overcrowded dormitories and are packed likes sardines with 12 persons to a room.”

Calls for reform

The crisis unfolding in the dormitories has led activists to call for broader reforms on living and working conditions for migrant workers beyond the coronavirus pandemic.

Working in a city without a minimum wage, they earn a fraction of the salaries of white-collar employees. The average migrant worker earns about $400 to $465 a month, compared to the average Singaporean monthly salary of $3,077, according to data from TWC2.

Some employers also don’t provide medical care or paid sick leave to migrant workers – the consequences of which became clear during the pandemic. Even as late as March, some employers discouraged their migrant workers from going to the doctor when they felt unwell, or docked their pay for taking the time off, said Leong.

And workers don’t have many avenues to address these issues; their visas are tied to their employers, who can terminate work permits at any time, so filing a complaint against your boss could jeopardize not only your job but your migration status.

“This present crisis actually reflects a far bigger systemic problem of the state being relatively fine or not so concerned about the welfare, the well-being, and the rights of migrants,” said Au, the NGO vice president.

Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower has previously said that it prosecutes employers who willfully refuse to pay workers, and has taken action against dormitory operators who fail to follow regulations. An operating company and its director were prosecuted last year after their dormitories were found to have broken lights and shower taps, and “filthy” living conditions.

In light of the coronavirus outbreak, however, some government leaders are acknowledging there is still much work to be done in improving migrant workers’ rights and standards of living.

“Should standards in foreign worker dormitories be raised? There’s no question in my mind, answer is ‘yes’,” wrote Minister Teo on Facebook in early April, as the first few dormitories were being locked down.

“I hope the Covid-19 episode demonstrates to the employers and wider public that raising standards at worker dormitories is not only the right thing to do, but also in our own interests,” she wrote.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong also thanked migrant workers for their contributions to Singapore and their cooperation during the pandemic in a press release on Tuesday.

“To our migrant workers, let me emphasize again: we will care for you, just like we care for Singaporeans,” he said. “We will look after your health, your welfare and your livelihood. We will work with your employers to make sure that you get paid, and you can send money home … This is our duty and responsibility to you, and your families.”

CNN’s James Griffiths contributed reporting