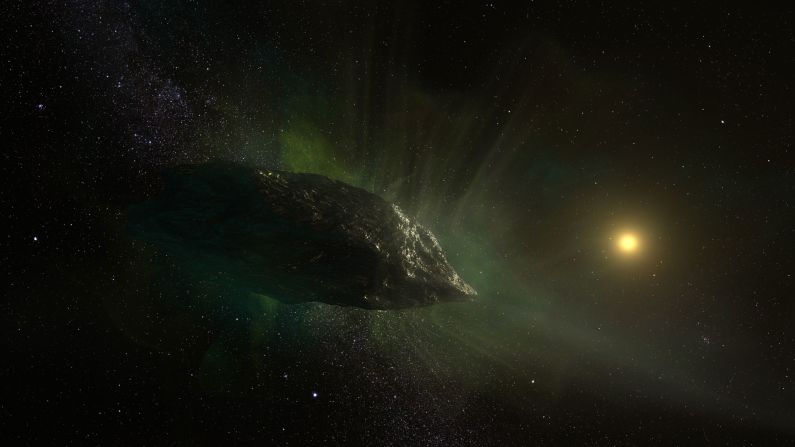

When interstellar comet 2I/Borisov entered our solar system last year, this time capsule from another place in the universe opened and revealed information about its origin, according to new research.

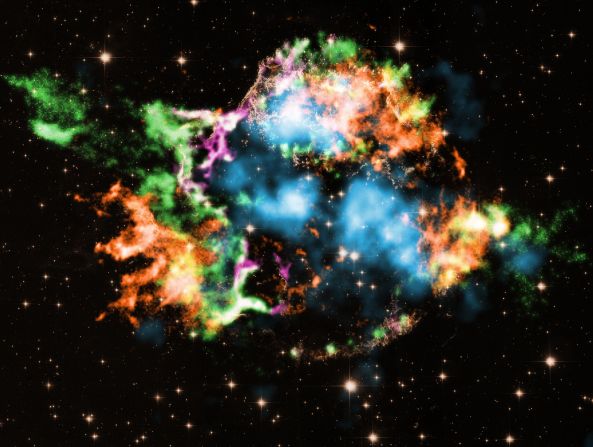

Since it was first observed in 2019, the comet has been streaming across our solar system and the heat of our sun has caused it to shed gas. Within that gas and the melting bits of the comet is information, some of which could be millions or even billions of years old.

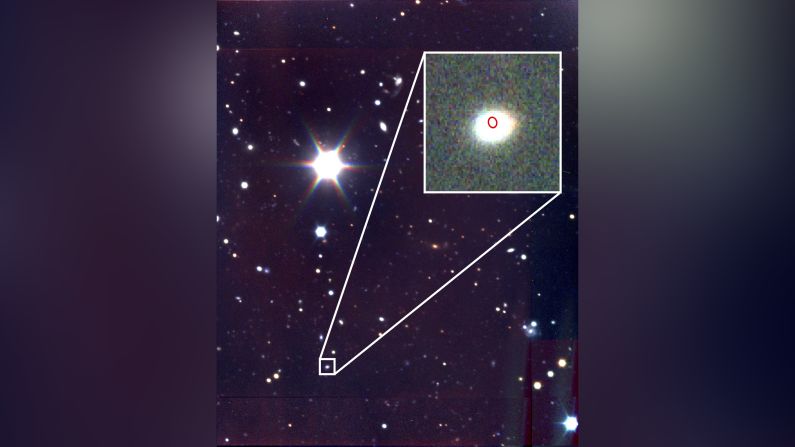

In December, astronomers ensured that telescopes in space and on the ground were oriented to observe the comet’s closest approach to Earth. It passed within 190 million miles of Earth, shedding more gas and dust evaporating through its cometary tail.

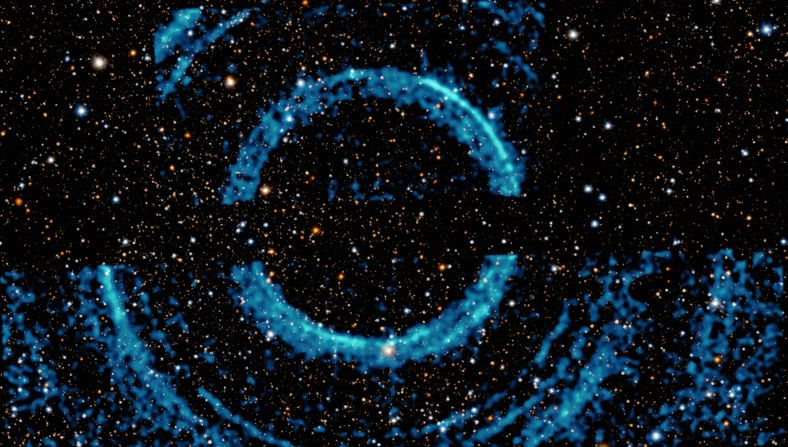

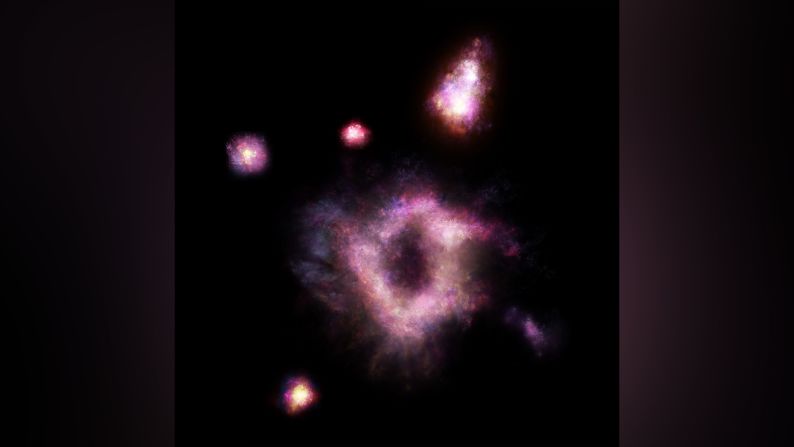

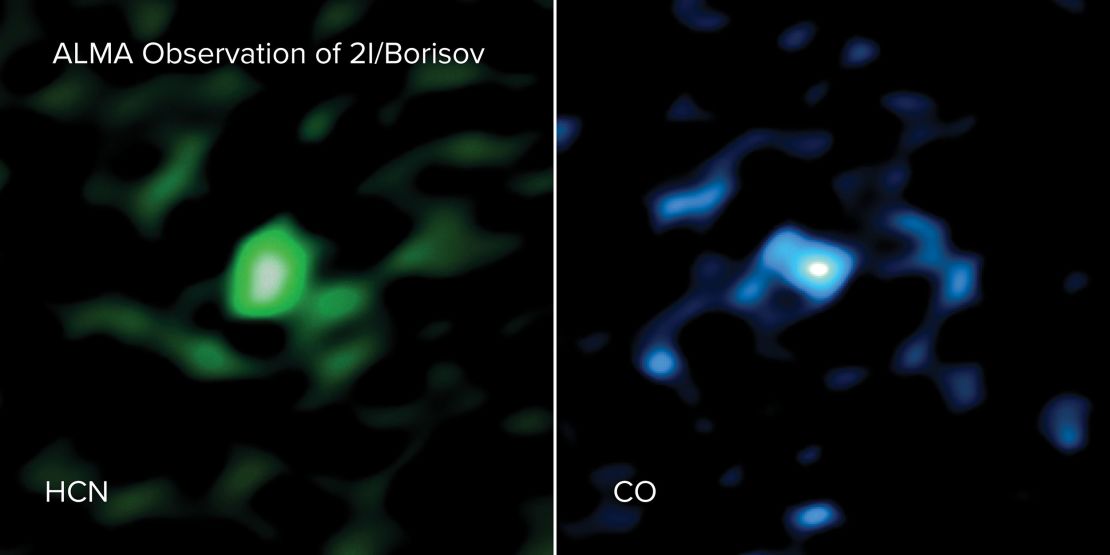

This close (for a comet) pass was observed by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array of telescopes in Chile, known as ALMA.

“This is the first time we’ve ever looked inside a comet from outside our solar system,” said Martin Cordiner, astrochemist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and an author of one of two studies on the comet that published Monday.

“And it is dramatically different from most other comets we’ve seen before,” he said in a statement.

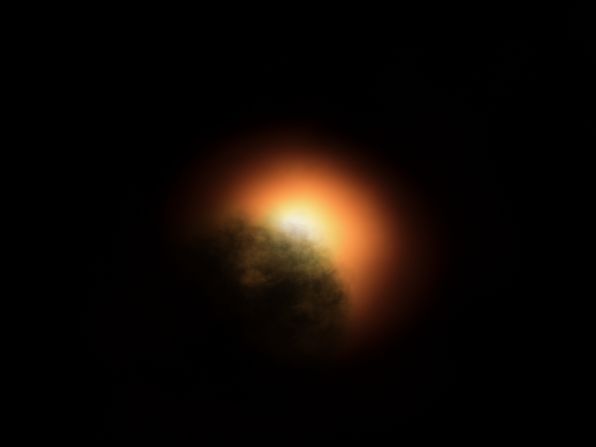

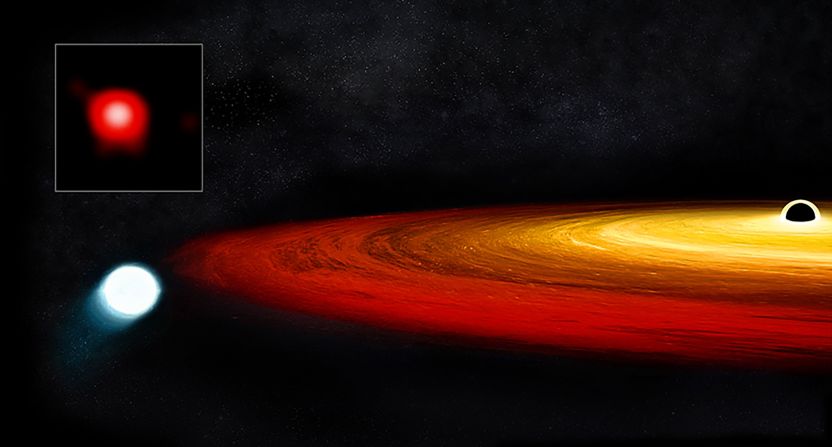

Astronomers could identify the gas streaming from the comet, which contained an unusually high amount of carbon monoxide – more than has been identified in a comet within two times the distance from the Earth to the sun, according to the study published in the journal Nature Astronomy. This suggests that the comet may have formed under different circumstances than those in our own solar system.

A second study about the nature of the carbon monoxide also published Monday in Nature Astronomy.

The amount of carbon monoxide is thought to be between nine and 26 times greater than the average comet in our solar system.

The also detected hydrogen cyanide, which was expected and the amount was similar to that found our solar system’s comets.

“The comet must have formed from material very rich in [carbon monoxide] ice, which is only present at the lowest temperatures found in space, below -420 degrees Fahrenheit (-250 degrees Celsius),” said Stefanie Milam, study co-author and planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland,in a statement.

Carbon monoxide is common in comets, but the amount appears to vary.

Astronomers believe this variation might be due to the particular region where the comet was formed, or how often a comet is brought closer to a star due to its orbit. This closer approach causes it to melt and shed elements that evaporate easily.

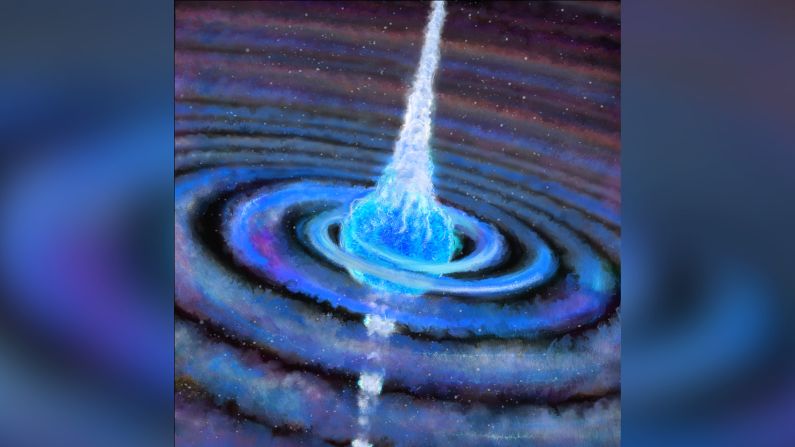

“If the gases we observed reflect the composition of 2I/Borisov’s birthplace, then it shows that it may have formed in a different way than our own solar system comets, in an extremely cold, outer region of a distant planetary system,” said Cordiner. This region can be compared to the cold region of icy bodies beyond Neptune, called the Kuiper Belt.

Comets can uniquely preserve information about how they were formed because most of the time, they’re far away from stars and cold enough that they remain unchanged.

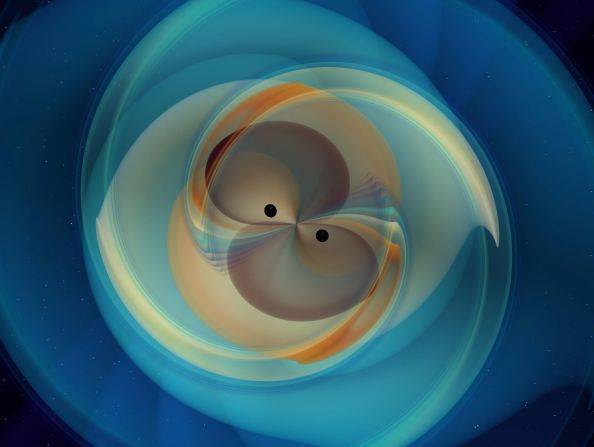

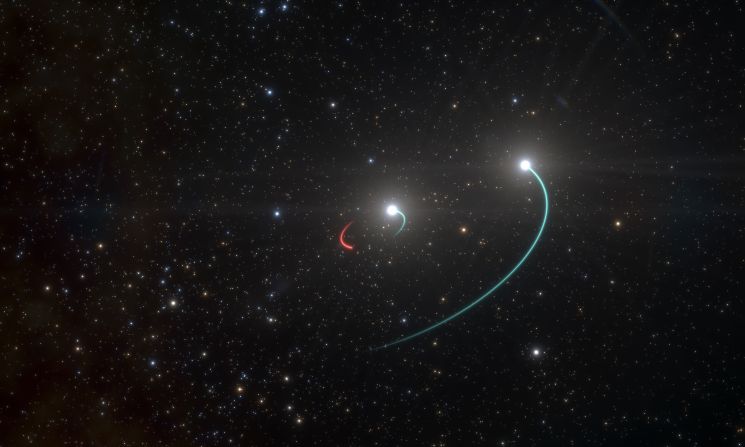

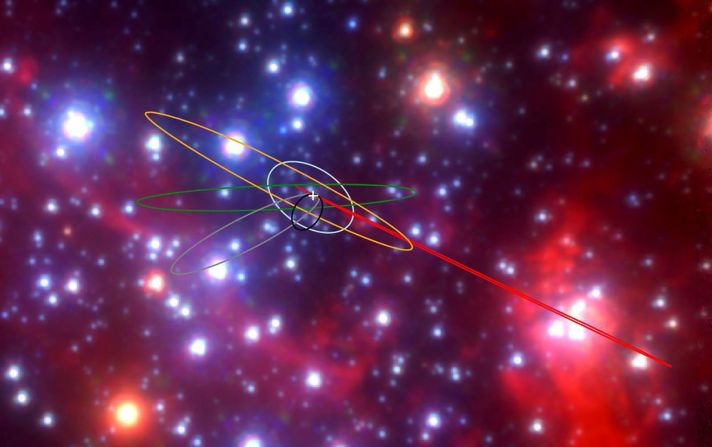

For now, astronomers don’t know what kind of star the comet orbited before being kicked out of its solar system and sent into ours. Astronomers suspect the eviction occurred when the comet interacted with the gravity of its host star or a giant planet in the system.

It’s been traveling on its own, for millions or billions of years, and then entered our solar system and was spotted in August 2019.

So where did it come from?

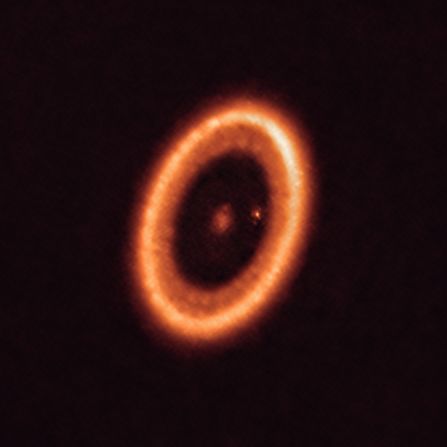

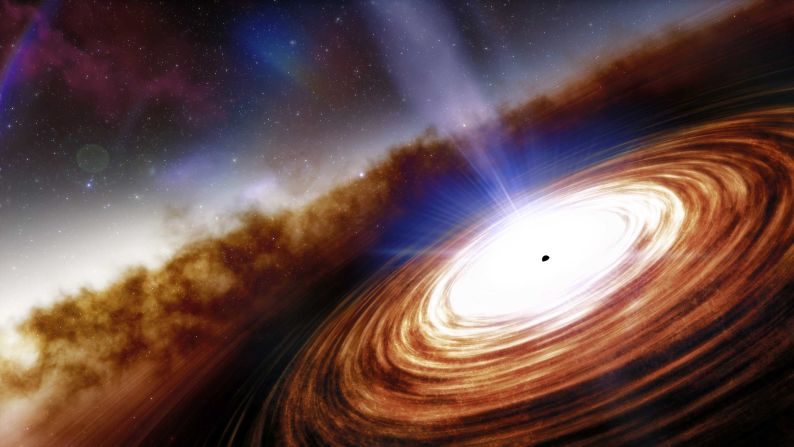

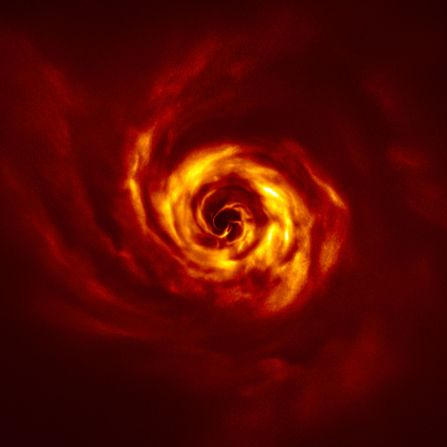

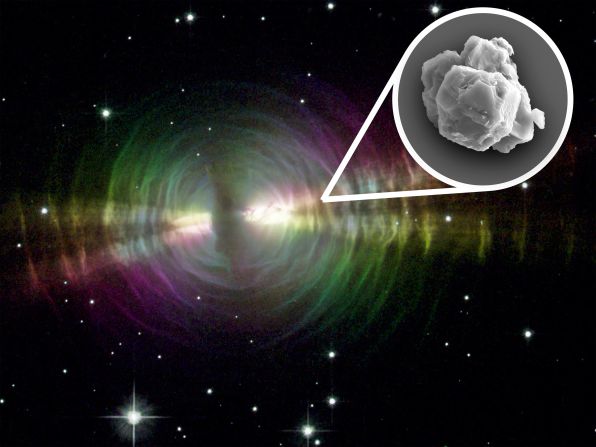

The comets in our solar system are leftovers from the material that makes planets, which was found in a protoplanetary disk around our sun.

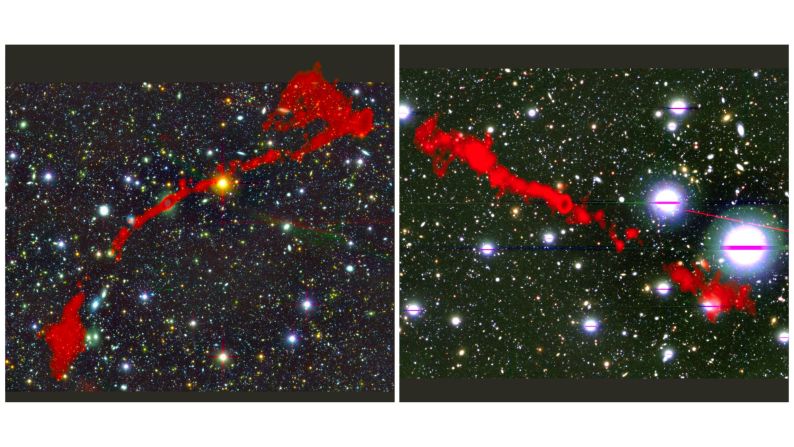

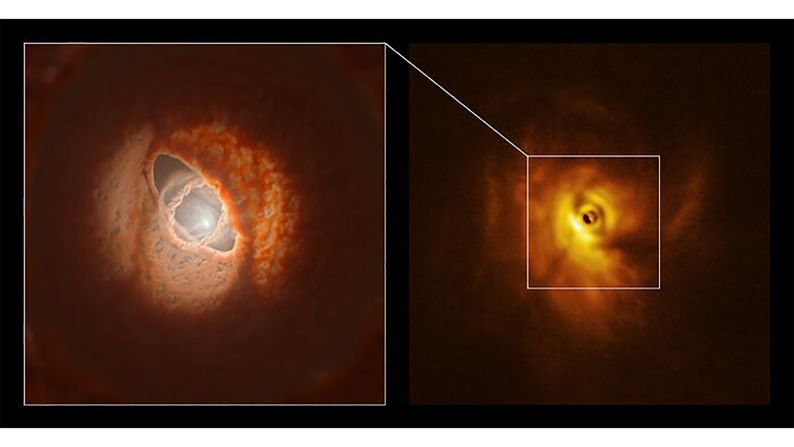

The ALMA group of telescopescan observe disks around younger versions of stars similar to our sun.

These protoplanetary disks contain gas and dust where planets pull together and form – and leftover pieces of this gas, dust and ice form comets. So it’s possible that the star this comet orbited was a younger version of our sun.

And the melting elements from the comet tell us what could be found in a protoplanetary disk around a star in another solar system.

“ALMA has been instrumental in transforming our understanding of the nature of cometary material in our own solar system – and now with this unique object coming from our next door neighbors,” said Anthony Remijan, study co-author and at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia, in a statement.

“It is only because of ALMA’s unprecedented sensitivity at submillimeter wavelengths that we are able to characterize the gas coming out of such unique objects.”

This is only the second interstellar object to cross into our solar system after ‘Oumuamua was spotted in 2017. Astronomers didn’t have long to observe it, and it was classified as an interstellar asteroid.

But 2I/Borisov is with us for longer. And its signature cometary tail gave it away as an interstellar comet.

The comet won’t remain in our solar system, despite the gravity of our sun, because it’s zipping along at 100,000 miles per hour. By June 2020, the comet will be well past Jupiter and on its way back to interstellar space.

“2I/Borisov gave us the first glimpse into the chemistry that shaped another planetary system,” said Milam.

“But only when we can compare the object to other interstellar comets, will we learn whether 2I/Borisov is a special case, or if every interstellar object has unusually high levels of CO (carbon monoxide).”