US President Donald Trump stunned world leaders and health experts on Tuesday when he announced he was halting funding to the World Health Organization, in the middle of the global coronavirus pandemic.

He first threatened to do so last week, accusing the WHO of mismanaging the spread of the novel coronavirus, and of not acting quickly enough to investigate the virus when it first emerged in China in December 2019.

Antonio Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations, which is the WHO’s parent organization, described the pandemic as unprecedented in a statement Tuesday and acknowledged that there would be “lessons learned” for future outbreaks.

“Once we have finally turned the page on this epidemic, there must be a time to look back fully to understand how such a disease emerged and spread its devastation so quickly across the globe, and how all those involved reacted to the crisis,” he said in the statement.

“But now is not that time … it is also not the time to reduce the resources for the operations of the World Health Organization or any other humanitarian organization in the fight against the virus,” he said, urging unity in the face of a pandemic that has killed more than 126,000 people globally.

What is the WHO?

The WHO is a UN agency founded in 1948, only several years after the UN itself was formed. The agency was created to coordinate international health policy, particularly on infectious disease.

The organization is comprised of and run by 194 member states. Each member chooses a delegation of health experts and leaders to represent the country in the World Health Assembly, the organization’s decision and policy-making body.

The member states directly control the organization’s leadership and direction – the assembly appoints the WHO director general, sets its agenda and priorities, reviews and approves budgets, and more.

The WHO has regional headquarters in Africa, North and South America, Southeast Asia, Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Western Pacific. There are more than 150 field offices globally, where staff on the ground work with local authorities to provide guidance and health care assistance, according to the organization’s website.

In the 70 years since its founding, the WHO has had its share of successes: it helped eradicate smallpox, reduced polio cases by 99%, and has been on the front lines of the battle against outbreaks like Ebola.

More recently, it is helping countries battle the dengue outbreak in South and Southeast Asia, providing local clinics and health ministries with training, equipment, financial aid and community resources.

But the WHO has also faced criticism for being overly bureaucratic, politicized, and dependent on a few major donors.

Where does it get its money?

The WHO is funded by several sources: international organizations, private donors, member states, and its parent organization, the UN.

Each member state is required to pay dues to be a part of the organization; these are called “assessed contributions,” and are calculated relative to each country’s wealth and population. These dues only make up about a quarter of the WHO’s total funding.

The rest of the three quarters largely come from “voluntary contributions,” meaning donations from member states or partners.

Of all the countries, the US is by far the largest donor; in the two-year funding cycle of 2018 to 2019, it gave $893 million to the WHO. Of this total, $237 million were the required membership dues, and $656 million was in the form of donations.

The US’ donations make up 14.67% of all voluntary contributions given globally. The next biggest donor is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, an American private organization.

It’s not yet clear whether the US’ cuts to WHO funding will be taken from assessed or voluntary contributions.

The next member country with the biggest contributions is the UK, which paid $434.8 million in dues and donations during that same time span, followed by Germany and Japan.

China contributed close to $86 million in assessed and voluntary contributions in that time period.

Why does this matter?

Here’s the issue: critics have long alleged that member states hold different levels of influence in the WHO due to their political and financial capabilities.

Major donors like the US are perceived by some as holding outsized influence, which has historically caused friction; during the Cold War, the Soviet Union and its allies left the WHO for a number of years because they felt the US had too much sway in the organization.

Recently, the same skepticism has been aimed toward the WHO’s relationship with China; critics have questioned whether the WHO is independent enough, given China’s rising wealth and power. They point to the WHO’s effusive praise of China’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, and the fact that China has successfully blocked Taiwan from gaining membership.

Taiwan is a self-governing democratic island which has never been ruled by the government of the People’s Republic, but is claimed by Beijing as part of its territory.

“WHO is a specialized UN agency composed of sovereign states,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian at a news conference on April 10. “Taiwan’s participation in the activities of WHO and other international organizations needs to be arranged in a reasonable and appropriate manner after cross-straits consultations under the One-China principle.”

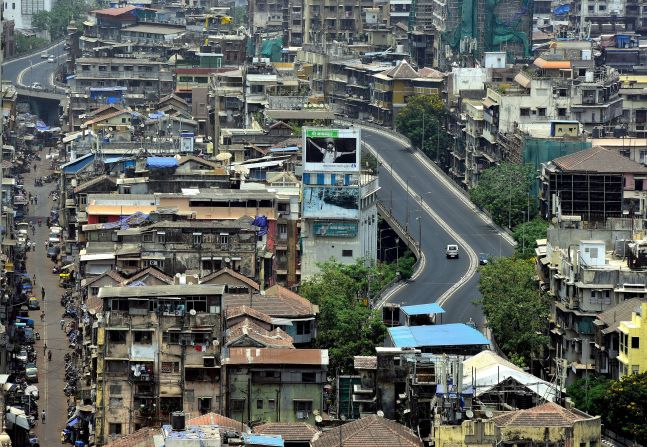

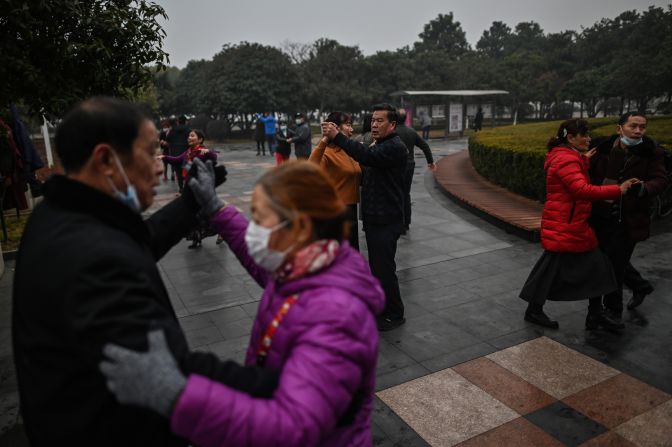

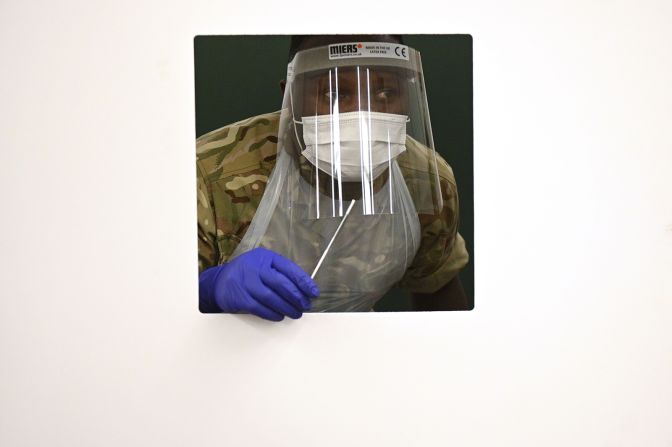

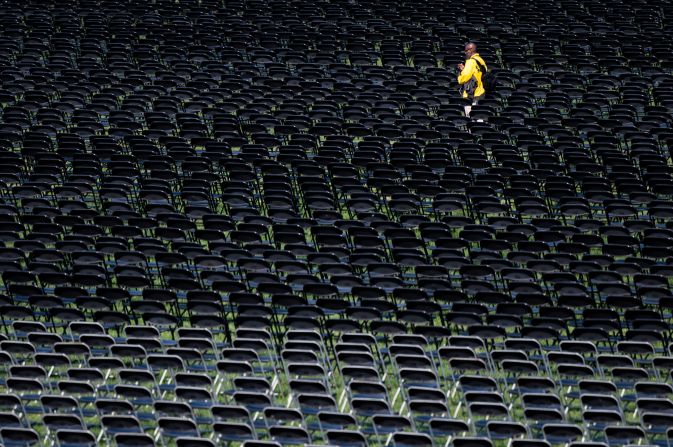

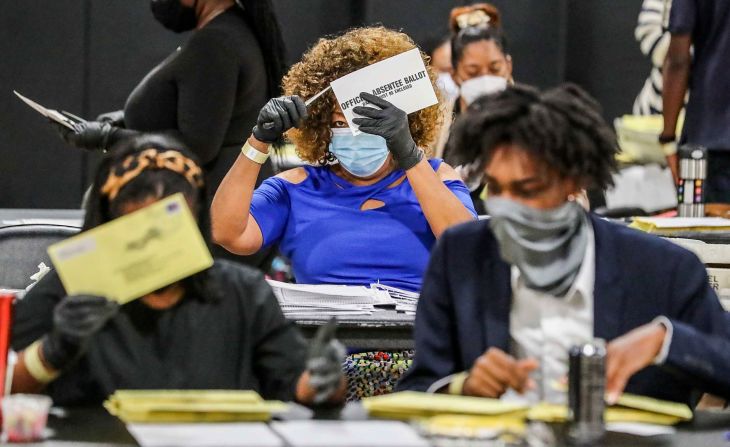

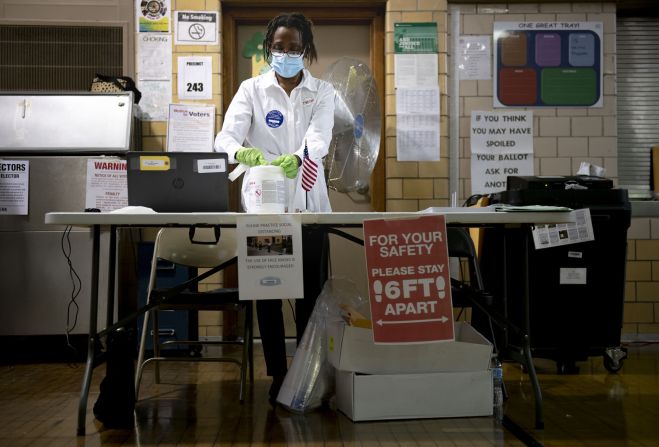

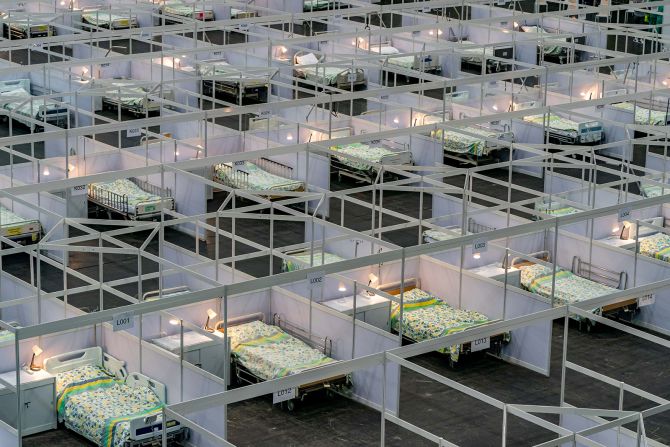

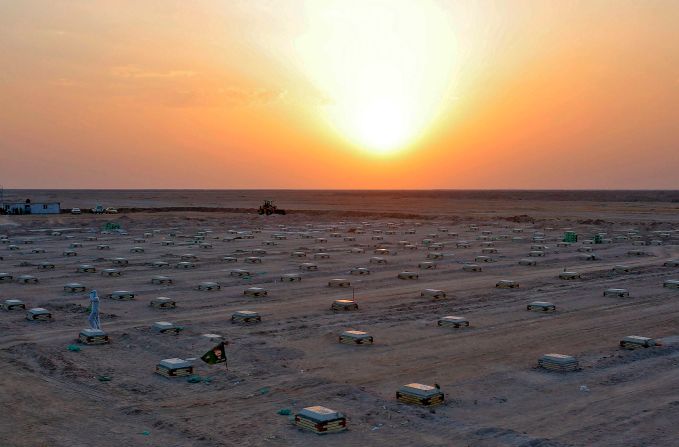

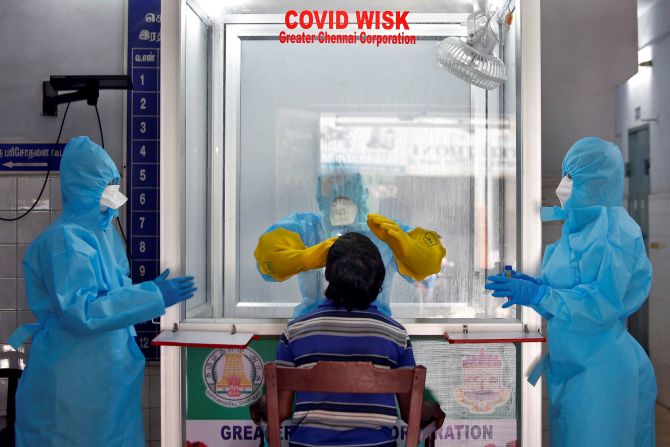

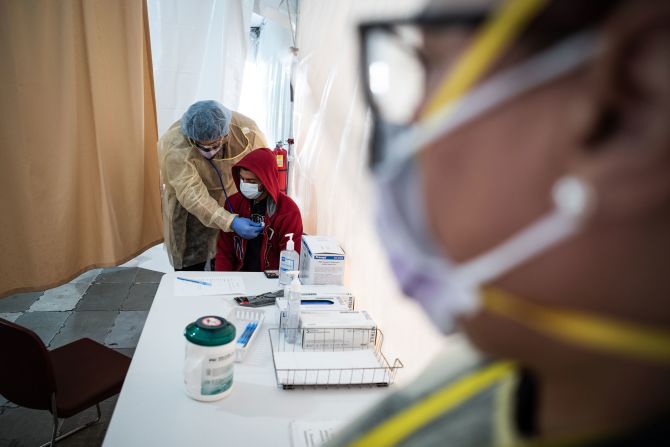

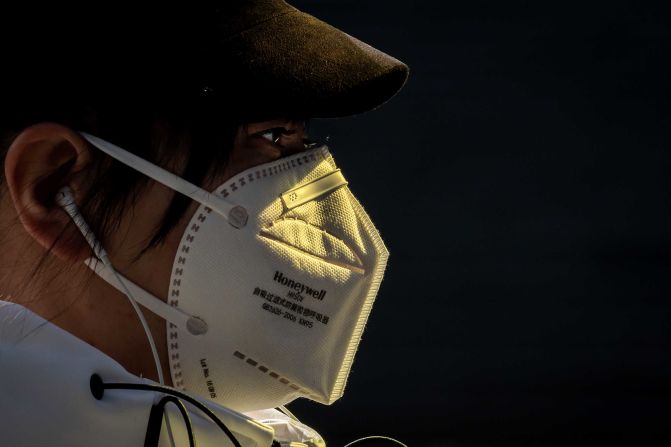

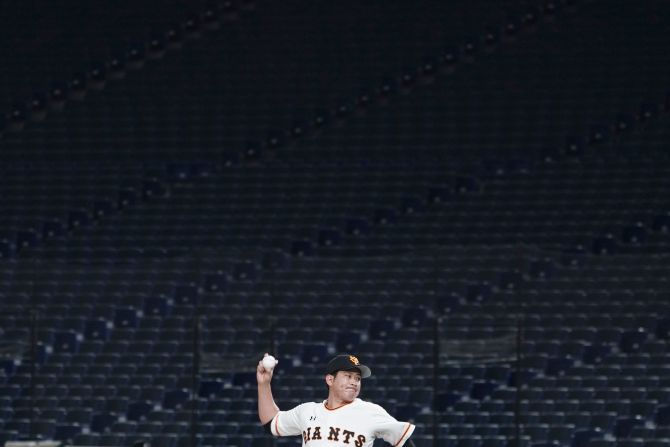

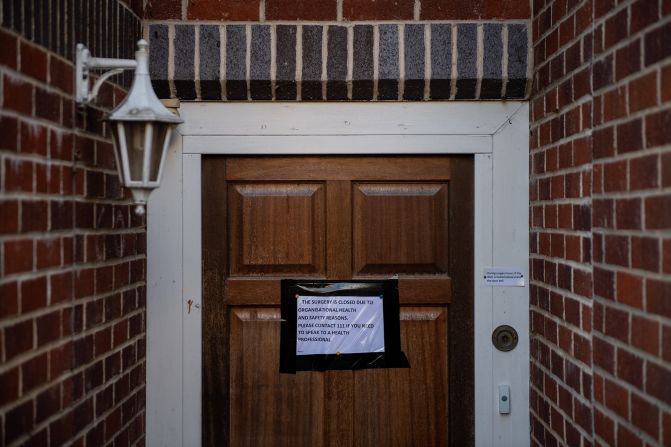

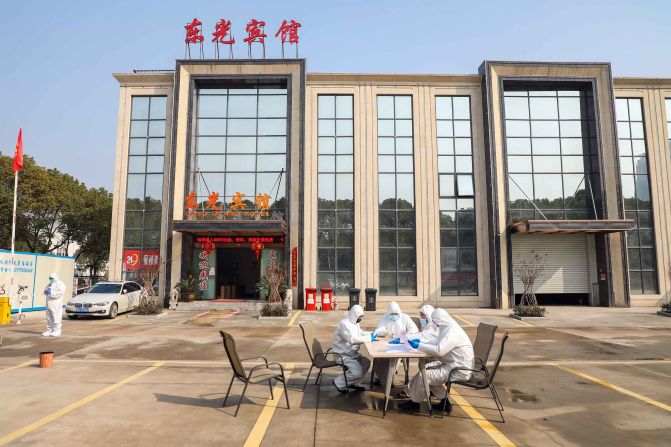

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

Trump and his administration alluded to the alleged Chinese increase in influence in regard to the pandemic on Tuesday.

“Had the WHO done its job to get medical experts into China to objectively assess the situation on the ground and to call out China’s lack of transparency, the outbreak could have been contained at its source with very little death,” Trump said.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was more blunt, claiming that the WHO “declined to call this a pandemic for an awfully long time because frankly the Chinese Communist Party didn’t want that to happen.”

The WHO has responded to these accusations by urging member countries not to politicize the pandemic.

“The United States and China should come together and fight this dangerous enemy,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in a statement last week.

CNN’s James Griffiths contributed to this report.