Donald Trump was in his element.

Playing to a cheering crowd at a Detroit-area auto parts plant in January, the president railed against disgraceful Democrats, bad trade deals and the dishonest media as he touted his record of creating jobs “like you have never seen before.”

The brewing coronavirus crisis merited only a brief mention at the end of his speech. He wanted to assure his audience that his administration had it “very well under control.”

“We think it’s going to have a very good ending,” Trump said.

Since then, an employee at the plant tested positive for coronavirus. Afterward, the plant ceased production, leaving its hourly workforce to collect unemployment. The company, Dana Inc., which has locations around the globe, has seen its stock price plummet by more than 40% amid fears of the virus’ uncontrolled spread.

As opposed to a good ending, there is currently no end in sight. Southeastern Michigan, where the plant is located, emerged as a coronavirus hot spot, at one point pushing the state’s caseload to among the top in the nation.

When Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, recently appealed to the federal government for help, Trump took offense at her criticism of the federal response and what he saw as her ingratitude. He lobbed insults, calling her “Gretchen ‘Half’ Whitmer” on Twitter and telling Vice President Mike Pence, the head of the coronavirus task force, “don’t call the woman in Michigan.”

While government officials and public health experts have devoted years to efforts to enhance US preparedness for a pandemic, a key factor went overlooked: a president like Trump.

His response to the Covid-19 crisis has been marred by many of the same traits that have characterized his presidency, including a penchant for false statements, deflection of blame, self-aggrandizement and bullying. The president’s approach made it more difficult for those around him who scrambled to mount a cohesive response to the pandemic, according to public health experts and other officials.

There was no contingency plan for a commander in chief who would deem the threat from Covid-19 “under control” when it was anything but. There was no tabletop exercise that simulated a President telling Americans the virus would “miraculously” disappear.

Nor did anyone anticipate that the millions of Americans who watch Fox News would see the mysterious, rapidly spreading novel coronavirus minimized and politicized for weeks.

There was no playbook for dealing with a public health disaster of this magnitude in Trump’s America.

“We have chaotic things happening out of the White House without any clear plan, without a comprehensive approach, without clear messaging, and the result is a lot of people are dying…who didn’t have to die,” said Tom Frieden, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under President Barack Obama.

“I can’t think of any precedent for what’s going on,” Frieden told CNN. “It’s mind-boggling.”

Trump inherited some of the difficulties that plagued the country’s early response to the crisis, to be sure. And even his critics acknowledge that no administration is fully prepared for a global pandemic with new challenges arising minute by minute.

“It is hard,” said Lisa Monaco, who served as Obama’s homeland security adviser and is a CNN national security analyst. She led incoming Trump administration officials through a pandemic tabletop exercise during the presidential transition. Though Monaco has also been critical of the Trump administration’s response during the pandemic, she added, “I have sympathy for the ability to answer questions and provide information in real time when the ground is shifting beneath your feet.”

As for Trump, asked to rate his own performance at a press conference last month, he awarded himself a perfect 10.

The president doubled down on that assessment during an unorthodox appearance in the White House briefing room Monday evening. Angered by growing criticism of his administration’s response, including a New York Times report published over the weekend, Trump used what was supposed to be a coronavirus briefing to play a White House-produced propaganda-like video promoting his efforts.

What you need to know about stay-at-home orders

“Everything we did was right,” he told reporters at one point.

“The truth is President Trump took bold action to protect Americans and unleash the full power of the federal government to curb the spread of the virus, expand testing capacities, and expedite vaccine development when we had no true idea the level of transmission or asymptomatic spread,” Judd Deere, a White House spokesman said in a statement to CNN. “The President remains completely focused on the health and safety of the American people and it is because of his bold leadership that we will emerge from this challenge healthy, stronger, and with a prosperous and growing economy.”

This account of how the US struggled to combat the novel coronavirus as it spread across the globe and onto American soil is based on dozens of interviews with doctors, scientists, front-line health care providers and current and former government officials.

The biggest threat

There had been warnings and hand-wringing at the highest levels for years.

Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates told a TED Talk audience in 2015 that in his mind, a pandemic virus had replaced nuclear war as the biggest threat to the US. In 2018, Emory University commemorated the 100-year anniversary of the 1918 flu pandemic, estimated to have killed at least 50 million people worldwide, and explored whether and how it could happen again. Johns Hopkins University conducted a live-action simulation dealing with a similar threat designed to show that preparing ahead of time was the only answer – that responding as it unfolded was untenable.

And just last year, the Trump administration ran its own exercise dubbed Crimson Contagion. Among the lessons learned: “The US lacks sufficient domestic manufacturing capacity and/or raw materials for almost all pandemic influenza medical countermeasures,” Dr. Robert Kadlec, the assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services, told a House panel in December 2019.

Months before that, Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar told a biodefense conference: “The thing that people ask: ‘What keeps you most up at night in the biodefense world?’ Pandemic flu, of course.”

The threat becomes real

In late December, the feared threat of the kind that had been so analyzed and so trained for suddenly became real. News began to trickle out of China about a cluster of acute respiratory illness cases seemingly linked to a seafood and animal market in the city of Wuhan.

“Everyone in this area of public health knew it was coming,” said Rebecca Katz, the director for the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University Medical Center. “It was sobering, and we were scared.”

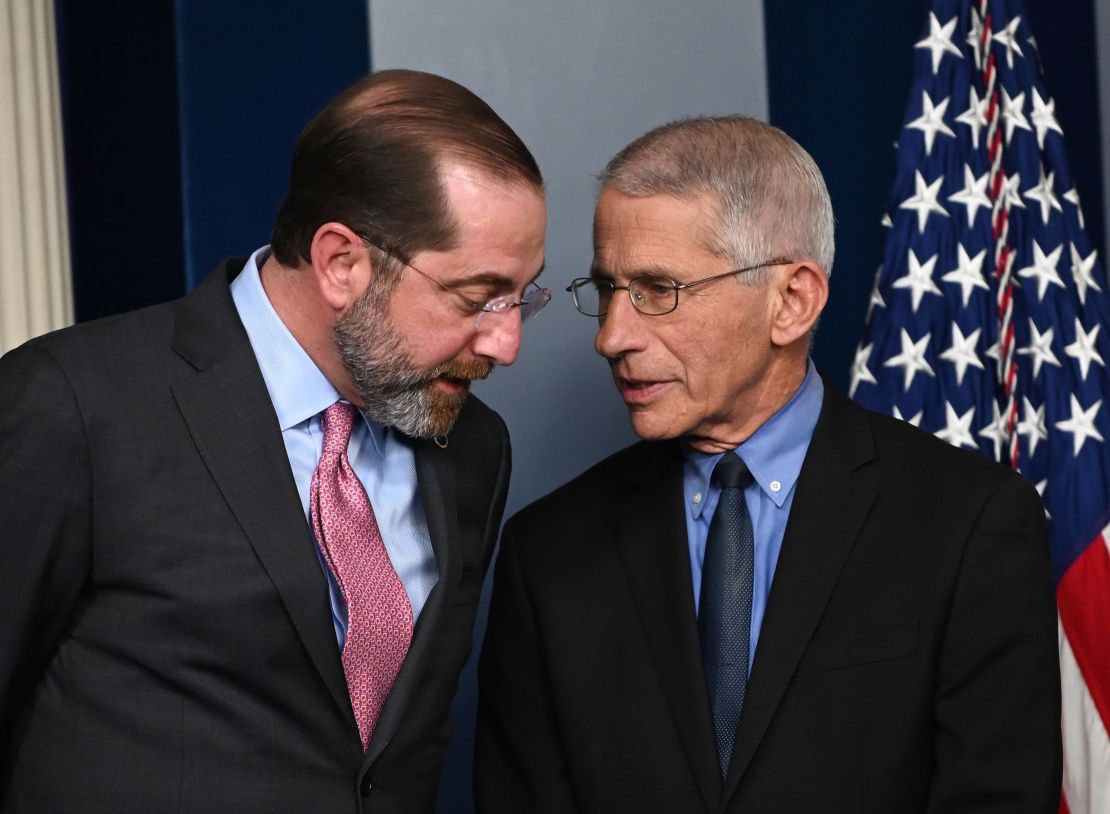

Azar, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and other top health officials quickly began convening daily meetings in January on the coronavirus threat, sources told CNN.

By late January, the National Security Council also began holding daily coronavirus meetings at the White House, said one person familiar with their discussions. For weeks, they were primarily focused on ways to prevent anyone infected or exposed to the disease – including American citizens – from traveling to the US.

At the same time, intelligence reports shared with the White House and Capitol Hill noted the threat of the coronavirus and warned that China was minimizing its impact.

Still, aides struggled to convey how serious the threat was in a way that would break through with the president, who was freshly impeached and on trial in the Senate.

When Azar was finally able to press the issue with Trump in January, the President appeared preoccupied, sources said. Rather than engage on the coronavirus, Trump lobbed questions at his HHS secretary about the sale of flavored vaping products.

As January drew to a close, the CDC’s top respiratory disease doctor said the agency was actively investigating the disconcerting possibility the virus could be spread by people not yet showing any symptoms.

As Americans, Dr. Nancy Messonnier cautioned, “we need to be preparing as if this is a pandemic.”

An administration official insisted Trump took the virus seriously from the start, noting that Trump created a task force in late January and was in touch with governors across the country.

But that wasn’t evident from the President’s public remarks. Just four days after Messonnier warned of a possible pandemic, Trump told the Michigan autoworkers he believed everything was under control.

It would not be the last time his assessment would strike a different tone than the experts whose duty it was to inform him.

Viruses don’t respect borders

If there’s one staple of modern pandemic preparedness plans, perhaps it is this: Viruses don’t respect borders. That same warning was included in the Trump administration’s own national biodefense strategy.

“Infectious diseases travel without visas and cross borders indiscriminately; infected travelers may not manifest any symptoms,” it states.

But the Trump administration’s first response, in late January, was to bar foreigners who visited China from entering the US. It bought the Trump administration time, but it was the only significant step the administration would take to try to contain the virus for at least a month. One former administration official said there was no one left at the National Security Council who could “viscerally understand” the public health threat the virus posed.

Within days, Americans evacuated from China would arrive at Travis Air Force Base in California.

Even then there were signs of trouble with the federal response.

Quarantined victims were welcomed by emergency response teams that had been equipped with baby wipes and construction worker-style paper dust masks. Those emergency workers then carried on with their normal lives, visiting restaurants, coffee shops and tourist attractions.

“They’re spraying down streets with bleach in China,” one first responder told CNN. “We would go straight from quarantine to Starbucks.”

As the CDC began distributing test kits to track the virus’s potential spread, Trump continued with his optimistic outlook.

It “looks like, by April, you know, in theory, when it gets a little warmer, it miraculously goes away,” he proclaimed at a political rally in New Hampshire on Feb. 10.

Days later, the CDC acknowledged some problems with the tests it had distributed that would effectively leave health officials blind to the extent of Covid-19’s spread across the US. The administration would continue to struggle for months to scale up testing.

Trump saw no need to wait for widespread testing to issue his own assessment.

“The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA,” he tweeted Feb. 24. “Stock Market starting to look very good to me!” he added.

That same day, the Dow Jones plunged more than 1,000 points amid news about coronavirus cases surging in Italy and South Korea.

‘Supply chain concerns’

For most of February, the Trump administration publicly downplayed the threat of the virus to American citizens, treating it mainly as a problem to wall off from the US. By then cases of the coronavirus had been circulating in the country for at least a month.

In a Feb. 7 statement, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo touted the State Department’s efforts to aid China’s battle with the coronavirus, noting the department helped deliver “nearly 17.8 tons of donated medical supplies to the Chinese people, including masks, gowns, gauze, respirators, and other vital materials.”

At that point, there were already scattered news reports about potential strains to the global supply chain and concerns that people were beginning to hoard medical-grade masks, potentially making it more difficult for health care workers to obtain them. Over at HHS, Kadlec – the same official who had previously warned Congress about shortages during a pandemic – had already begun discussing when and how to begin using the Defense Production Act, a source said.

Within weeks, it was clear the US would face dire shortages of its own.

On Feb. 20, emails from officials with the CDC were landing in inboxes of public health departments across the country with an ominous instruction suggesting a growing sense of urgency.

The agency acknowledged “supply chain concerns” related to the Covid-19 response and urged recipients to hang onto any personal protective gear they may have, even if it is “past its intended shelf life,” according to one of the thousands of emails obtained by CNN under public records act requests.

It was around this same time that Carter Mecher, a senior medical adviser to the Department of Veterans Affairs, offered a bleak assessment about the path ahead.

“We should plan assuming we won’t have enough PPE (personal protective equipment) — so need to change the battlefield and how we envision or even define the front lines,” he wrote in an email obtained by CNN to a group of public health experts who had worked on pandemic issues going back to the George W. Bush administration.

One public health expert on the email chain described it as something of a shadow campaign to convince administration officials to respond more urgently.

The discussion included the need to quickly implement school and business closures, based on data on the outbreak coming from China and the Diamond Princess cruise ship.

Included in the string of messages were officials from Health and Human Services, the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security, the Army and the Department of Agriculture.

“One of the things that we were hoping is people were watching our conversations,” the participant said. “We weren’t trying to change things from the top down. All we could do is we were influencing friends and colleagues we have known a long time.”

By late March, the State Department was fielding questions about whether it had been a mistake to ship critical medical supplies to China.

Those medical supplies were “from private donors, so it wasn’t from the US Government per se,” said Jim Richardson, the director of US Foreign Assistance Resources at the State Department.

The decision to keep critical medical supplies on US soil didn’t come from the coronavirus task force until late March, when severe shortages were already apparent in the US, administration officials said. By early April, the US was buying personal protective equipment and ventilators from Russia, facilitated by the State Department.

‘This could be bad’

Over at the CDC, Messonnier had been delivering stark warnings about the virus.

In a briefing on Feb. 25, she told reporters, “We are asking the American public to work with us to prepare in the expectation that this could be bad.”

She added that “disruption to everyday life may be severe.”

That was the day Messonnier got the President’s attention – and not in a good way, sources said.

The president was wrapping up a swing through India, and he and some of his aides were furious when they saw those comments, sources said, believing Messonnier was overinflating the threat of Covid-19.

In a separate briefing on Feb. 25, Azar attempted what some within the CDC saw as an effort to clean up Messonnier’s comments. He said she was simply trying to be transparent about potential steps that might be necessary.

“Might,” Azar said. “Not will. We cannot make predictions with any degree of certainty about how a virus will spread or what will happen.”

HHS did not respond to requests for comment.

When Trump returned from India the next day, he appeared in the briefing room to offer reassurances rather than warnings.

“It’s a little like the regular flu that we have flu shots for. And we’ll essentially have a flu shot for this in a fairly quick manner,” Trump said of the coronavirus that was already spreading like wildfire across the globe. “We’re ready for it. We’re really prepared.”

Messonnier would soon disappear from public coronavirus briefings, though a CDC spokesman insisted, “Dr. Messonnier continues to contribute to the response and is a vital asset to the agency.”

A senior CDC official directly involved in the agency’s coronavirus response said, “giving the science behind something shouldn’t make you a political target, but she was.”

The same official was similarly dismayed when the president toured the CDC in early March and proclaimed, apparently without warning, “anybody that wants a test can get a test. That’s what the bottom line is.”

That came as news to those directly involved in the process at the CDC, the source said.

‘They’re scaring the living hell out of people’

As is often the case, Fox News and Trump were in lockstep.

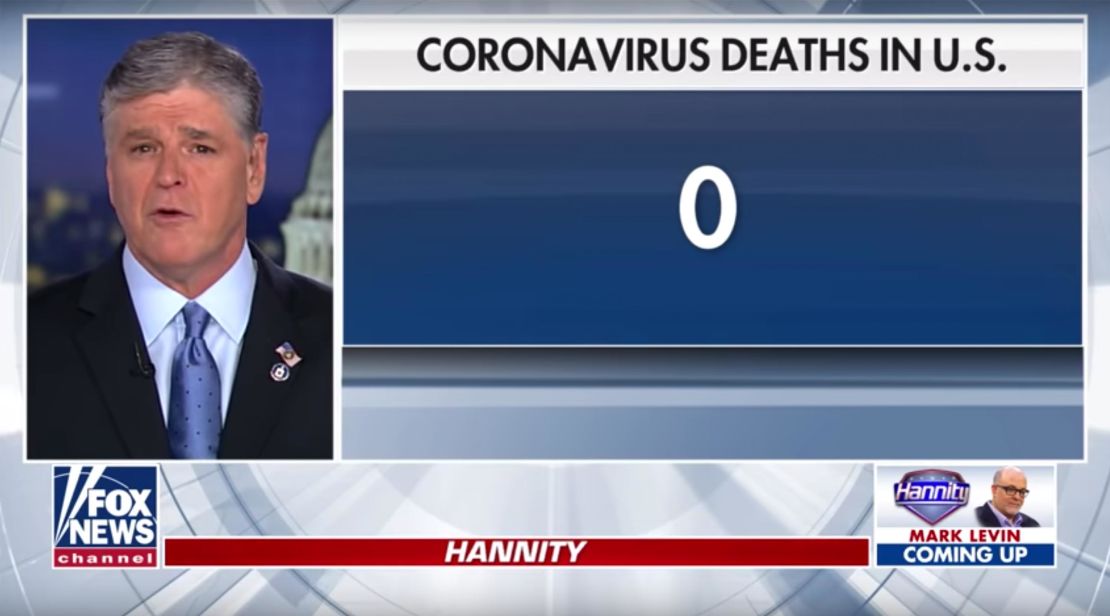

The visual graphic behind Fox News host Sean Hannity on Feb. 27 must have been reassuring to his millions of viewers, many of them elderly and particularly susceptible to the virus.

Under the headline, “Coronavirus Deaths in the U.S.,” was a number Hannity wanted his audience to know for context.

A lone zero filled the otherwise blank screen.

It was typical of the network’s coverage in February and early March. As the pandemic loomed, some network hosts and pundits routinely downplayed the medical nature of the threat and said it was being weaponized by the media and Democrats to attack the President.

“They’re scaring the living hell out of people,” Hannity said during a March 9 broadcast. “And I see it, again, as like, oh, let’s bludgeon Trump with this new hoax.”

Moments later he defended Trump’s response.

“No president ever acted faster,” he said.

Tucker Carlson, who hosts a Fox News show that Trump watches regularly, held another view. He was concerned that Trump was not giving Covid-19 the attention it deserved. He traveled to Mar-a-Lago where he personally delivered a message to the president: The virus posed a real threat and it could overwhelm the health care system, sources said.

Carlson’s warnings continued on air, too. “The Chinese coronavirus is a major event, it will affect your life and by the way, it is definitely not just the flu,” Carlson said in a broadcast in early March.

In response to questions, a Fox News spokesperson defended the network’s coverage.

10 out of 10

Before Trump fully grasped the threat posed by the novel coronavirus, he understood the danger of bad press, and the Trump administration was getting pummeled.

Trump had sidelined Azar from his role leading the coronavirus task force, replacing him with Vice President Mike Pence on Feb. 26. The Federal Reserve had announced an emergency rate cut but investors were still panicked. And the Trump administration had blindsided European allies with a sudden decision to evacuate American citizens from the Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Japan.

So, Trump and his advisers decided on an Oval Office address on March 11 announcing new travel restrictions from Europe. But he botched the details and instead created widespread confusion and sparked panic among Americans abroad.

Within a week, the Dow would erase all of its gains since Trump had taken office.

“I think he was pissed that his economy got f—– with,” one of the President’s allies said. “It took a while to get over that.”

In the days after his Oval Office address, advisers privately pressed Trump to put more faith in his health care officials, like Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, rather than his economic advisers, one adviser said.

The message to Trump was: “This is a war and these are your generals,” the adviser said.

They encouraged Trump to view himself as a wartime president, and the framing seemed to appeal to him.

Members of the task force also confronted Trump with a disturbing study coming out of Britain. If the US opted to just “ride it out,” as some of Trump’s economic advisers were recommending, 2.2 million Americans could die during the pandemic.

The number was stunning. And it stuck with Trump, the adviser said.

By then, Trump had decided he should play a more visible role in the response. Sources said he had noticed New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo getting public praise for his daily televised briefings, which included a slideshow presentation of the horrific data of the day, a projection of what was to come and a stern talking to for New Yorkers.

Not one to cede the spotlight, the reality-star-turned-commander-in-chief began appearing at the podium in the White House briefing room, eventually pushing the briefings later in the day so they would get higher viewership on television.

When he took the podium on March 16, Trump announced new social distancing guidelines for the nation.

It appeared Trump was finally taking the coronavirus seriously. He told the public that “each and every one of us has a critical role to play in stopping the spread and transmission of the virus.”

Then he rated his response so far as a 10 out of 10. “I think we’ve done a great job.”

On Sunday, Fauci, one of Trump’s top medical advisers, acknowledged on CNN’s “State of the Union” that putting social distancing measures in place sooner would have saved some of the more than 20,000 who have died from the virus in the US.

“I mean, obviously, you could logically say that if you had a process that was ongoing and you started mitigation earlier, you could have saved lives,” Fauci told host Jake Tapper. “Obviously, no one is going to deny that. But what goes into those decisions is complicated.”

Fauci sought to clarify his remarks shortly before Trump spoke on Monday evening. He explained that he was responding to a “hypothetical question” when he said more could have been done to save American lives. Fauci said his response “was taken as a way that maybe somehow something was at fault here” and said a remark he made about “pushback” to some of his recommendations from within the administration was a poor choice of words.

He told reporters Trump accepted a formal recommendation by himself and Dr. Birx to enact a nationwide 15-day mitigation period beginning last month, and to extend it another 30 days when they concluded more time was needed to slow the spread of the virus.

Others were bluntly critical of the President.

“Sadly, President Trump has made pretty much all the mistakes you can make,” said Laura Kahn, a public health expert who has studied leadership challenges during epidemics. “China had given the Trump administration about two months to prepare for this. They just squandered it by minimizing the severity, downplaying it, making false reassurances.”

Ali Nouri, president of the Federation of American Scientists, called the federal response to date “grossly inadequate.”

“We’re not letting the science drive the conversation,” Nouri said. “We’re letting the Dow Jones Industrial Average drive the conversation and that has been a problem and that’s why we’re playing catch up.”

Frieden, the former CDC director, faulted the administration for “sidelining” his former agency.

“What a different world we would live in today if Dr. Messonnier, who is our country’s top expert in how to fight this kind of condition of viral pneumonia, had been speaking to us every day, just as frankly, just as accurately, just as honestly, as she did in January and February,” Frieden said. “We would have gotten used to the idea, perhaps, that we were going to have to do some drastic things.”

The need to react quickly to an emerging threat, he predicted, will be among the most painful lessons of the Covid-19 crisis.

“If New York City had locked down two days before it did, half the people who died would not have died. Because it was doubling every two days,” said Frieden, who lives in Brooklyn. “Speed is incredibly important.”

‘A lot of life lost’

Don McMurray has worked for nearly 17 years at that auto parts plant Trump spoke at in Michigan. He said he felt the company didn’t do enough to protect its workforce early in the coronavirus outbreak.

“People were getting nervous and so was I,” McMurray said. A spokesman for Dana, Inc., insisted “our top priority remains the health and safety of our people.”

Since the plant has closed, management has continued to notify workers of additional coronavirus cases that have popped up among the workforce, McMurray said.

The 57-year-old manufacturing technician doesn’t know when the plant will reopen and has applied for unemployment benefits. Despite his application going through, he said he still hasn’t received a payment. When he calls to check on the status of his claim, he gets messages that the system is overloaded.

He remembers the day Trump spoke at the plant, but he doesn’t want to get into all of that. He is, however, perplexed about why America’s response has been so flat-footed.

“It’s been a lot of life lost behind all of this,” McMurray said. “I’m just surprised that our country was kind of slow to react to this.”

Kylie Atwood, Nick Valencia, Kaitlan Collins, Jeremy Diamond, Kevin Liptak, Bob Ortega, Vivian Salama, Blake Ellis, Melanie Hicken