More than a million farmworkers aren’t hunkered down at home as the coronavirus pandemic paralyzes much of the country.

Their labor – in fields, orchards and packing plants – is keeping food on America’s tables.

But workers and groups who represent them are sounding an alarm. Their warning: As the virus spreads, many farmworkers are living and working in conditions that put their health particularly at risk. And if outbreaks hit farmworker communities hard, they say, that could put the nation’s food supply at risk, too.

Growers and farmers say they’re doing everything they can to keep production going and keep employees safe, including scaling back the number of workers they’re transporting on buses, spacing workers out more as they harvest and increasing the number of hand-washing stations.

But workers and advocates who spoke with CNN detailed concerns about lapses in on-the-job safety, such as some farms that lack soap and protective equipment, and others that fail to enforce social distancing guidelines. Limited access to medical care and crowded living conditions, they said, are also major hurdles to keeping workers healthy.

Greg Asbed fears it’s not a question of if, but when, a devastating outbreak will hit. As a co-founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, which represents thousands of farmworkers in Florida, he says rural communities like his aren’t prepared for a health crisis.

“Once the virus takes root in a town like Immokalee, it will take off like wildfire,” he says. “That’s our fear … We will see this problem explode.”

Erik Nicholson, vice president of United Farm Workers, says it’s not a hypothetical. In the last two weeks, he says he’s heard about dozens of farm workers testing positive for the virus in Washington state, where he’s based.

“We’re living this in real time,” he says. “And the fear and the anger is rising.”

Workers say they’re bringing supplies from home and hoping they won’t get sick

At one orchard where cherries, pears and apples are grown in Washington’s Yakima Valley, workers recently began bringing their own soap from home to wash their hands because the company wasn’t providing any.

“We were feeling very desperate, very helpless, very disillusioned, because no one was supporting us or giving us anything to protect ourselves. No gloves, masks or disinfectant – nothing,” Maria, a worker at the orchard, told CNN. “We feel forgotten, and really terrified and afraid.”

The 37-year-old was one of several workers across the country who spoke with CNN on the condition that only their first names be used, saying they feared they’d face repercussions at work for sharing their stories.

Over the past two weeks, Maria says she’s watched the number of workers at the orchard drop, day by day, amid growing concerns about their safety. Many have young children, she says, and were scared they’d bring the virus home to their families. But Maria says staying home isn’t an option for her. She was already out of work for two months this year due to an injury and burned through her savings.

“We have to keep working, even though we’re afraid something is going to happen,” she says. “We surrender ourselves to God and hope.”

If she gets sick, Maria says she’s told her children not to take her to the hospital. Her biggest fear is dying alone there and leaving her family with crushing medical debts.

Carmen, a 44-year-old worker at a strawberry farm in Oxnard, California, says she’s been trying to remind people about social distancing guidelines, but fellow workers aren’t heeding her warnings and the company isn’t forcing anyone to stay six feet apart.

“Every time you hear a sneeze or a cough, you think, ‘God, don’t let it be this virus.’ We are taking a risk. We are afraid, but at the same time we don’t have a choice. If we don’t work, we can’t pay our rent. We can’t buy food,” she says.

Like many workers, she’s started carrying a document that notes that she’s an agriculture worker who the government considers “essential” – a description authorities have used to describe the work of employees and businesses that are too critical to stop during this crisis.

Carmen hopes it will help her if she gets stopped by police or immigration authorities. But as The New York Times reported recently, there’s no guarantee it will.

“We are supposedly working so other people can be at home, so they can have food,” she says. “They called us ‘essential workers,’ but we don’t have any rights.”

Growers say they are doing everything they can to protect workers

At least half of farmworkers are undocumented immigrants, according to government estimates. Many don’t have health insurance or receive sick leave.

Recently passed federal legislation make farms with less than 50 workers or more than 500 workers exempt from requirements to provide paid sick leave, says Nicholson of United Farm Workers.

“Neither of these exclusions make common sense when you’re talking about protecting the food supply,” he says. “There’s a significant economic disincentive for workers to do the right thing.”

But Dave Puglia says even growers who aren’t required to extend sick leave provisions are doing so.

Puglia, the president and CEO of Western Growers – which represents farmers in Arizona, California, Colorado and New Mexico – says doing everything possible to protect workers is a top priority. So far, he says, major outbreaks haven’t been reported at produce farms, but he says the possibility is something that has many growers “walking on eggshells.”

“It’s a huge concern. … The nation needs farmers and farmworkers to continue providing food, and obviously if the virus sweeps through the workforce, that will inhibit our ability to continue to providing food to the country,” he says. “A lot of people are going to great lengths to keep those workers safe.”

Whenever possible, social distancing measures are being implemented, he says. But Puglia says the way some crops, like lettuce, are harvested, requires workers to stand close together.

In Florida, some growers have started buying groceries for their workers, trying to limit their trips to the store, said Mike Carlton, director of labor relations for the Florida Fruit & Vegetable Association. Others have set up additional handwashing stations and have been regularly briefing employees about how to stay safe.

“Fortunately we are in a position where we are able to continue to harvest at this point. … The best we can do is take the most active measures we can to protect those workers,” Carlton said. “The only other measure is to stop them from working, and we can’t do that and continue to supply the country with food.”

In upstate New York, where novel coronavirus cases among farmworkers are starting to pop up, concern is growing, says Mary Zelazny, CEO of Finger Lakes Community Health. Farmers there are trying to protect workers, she says, but aren’t always sure what steps to take. On a recent call with farmers in the region, she says, questions came up about whether gloves should be warn during harvests and best practices for disinfecting trucks that have multiple drivers.

“There’s fear on everybody’s part,” she says.

Cramped conditions are a ‘recipe for an outbreak’

Irma couldn’t believe her eyes this week when she looked across the Walmart parking lot near her home in eastern North Carolina.

A large bus pulled in, full of workers.

For weeks the 36-year-old had been taking extra precautions to protect herself. So had her employer, a produce packing company, where she says workers have been encouraged to wear protection and wash their hands more often. Irma says for her, the bus was a troubling sign that other employers and workers aren’t taking the situation as seriously.

“They aren’t keeping their distance like they’re supposed to,” she says.

Buses and vans packed with workers are a typical sight in farming communities across the country as the harvest season kicks into high gear. So are camps – often located on farm property – where workers live in cramped conditions.

“It’s a recipe for a widespread outbreak,” says Nicholson of United Farm Workers.

Living conditions for migrant workers are “chronically and extremely overcrowded,” says Asbed of the Coalition of Immokolee Workers. Sometimes, he says, 10-12 people are housed in one single-wide trailer.

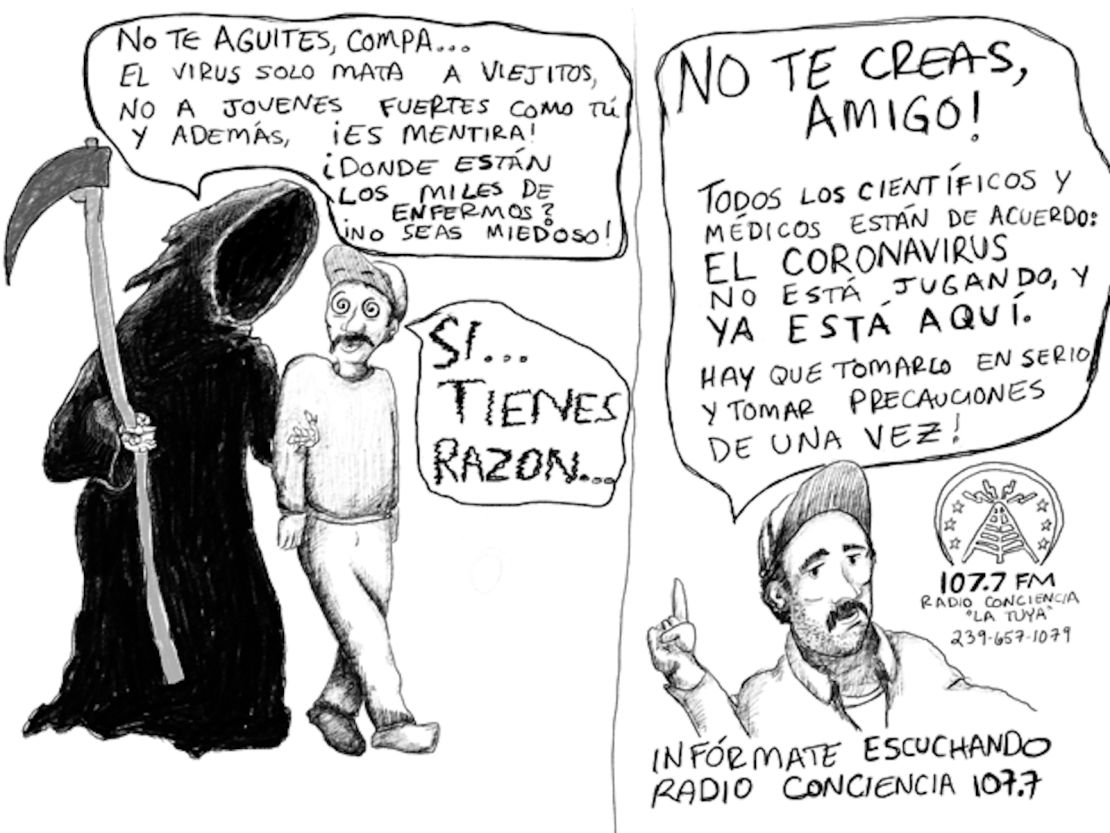

The organization has been posting flyers in stores and on social media to educate workers about risks the virus poses.

But there’s only so much they can do, he says.

“It’s a simple fact that if somebody living in a situation like that contracts the virus, it’s just a matter of time before everybody else in that same housing unit does as well,” he says.

That raises another question that health officials in upstate New York are weighing, says Zelazny, whose health center has been helping with coronavirus testing in farmworker communities. When farmworkers test positive, where can they go to quarantine and recuperate?

“We’re very worried about what are we doing with these guys as they convalesce?” she says. “They’ve got to go somewhere. And there’s no place to go.”

Farmworkers already had a hard time getting medical care. Now it’s getting harder

On top of all of the environmental risks farmworkers face, Sylvia Partida, CEO of the National Center for Farmworker Health, says she’s been hearing troubling reports from community health centers she works with across the country.

Some are worried they may have to curtail the services they offer to farmworkers because of funding shortages, she says, and it couldn’t come at worse time.

“Clinics might not be able to function,” she says. “There’s going to be an impact in the access that farmworkers have to healthcare services, and really also to information that will help protect them and provide them with information about how they protect themselves.”

While the massive aid package Congress recently passed provided money to community health programs, Partida says it didn’t specifically earmark funding for farmworker health. That, she says, means mobile clinics and other crucial programs for migrant workers could very easily get lost in the shuffle of competing priorities for limited resources.

“It’s already happening,” she says. “Health centers have had to furlough staff. They’ve had to close some of their sites.”

Mónica Ramírez was already concerned about the toll the coronavirus could take on farmworkers. Learning that some clinics are scaling back services made her even more worried.

“I was shocked,” says Ramírez, the president of Justice for Migrant Women, which advocates for workers’ rights.

“They are being put out on the frontlines to continue feeding this country,” she says, “and we cannot stand by and allow them to go without the care they need.”

Advocates argue the food supply is at risk. These are steps they say could help

In Florida, Asbed is pushing for officials to set up a field hospital in his community while there’s still time.

“It is quite possible that in a matter of a couple weeks here in Florida we may not have enough people to harvest the state’s fruits and vegetables,” he says. “That’s just an absolutely predictable outcome of the current configuration of things.”

On the national level, advocates who spoke with CNN said several policy changes could have a significant impact on the situation:

• Requiring farms – no matter their size – to provide sick leave for workers

• Earmarking federal funding to guarantee healthcare services for migrant farmworkers

• Covering the cost of Covid-19 testing and treatment regardless of immigration status

Maria is hoping a longer-term solution will emerge from this crisis, a way for undocumented farmworkers to come out of the shadows.

Being officially deemed “essential workers” was a small step in the right direction, she says. But officials are sending mixed messages.

“It’s contradictory. It’s an achievement that they’re calling us this,” she says. “But without any benefits, it’s like saying, ‘you are good, but you are not important.’”

Once the pandemic passes, she says, President Trump and other leaders in Washington should remember that they stayed in the fields and didn’t falter.

But no matter what, Maria says she’ll be getting up in the morning and heading back to work.

She knows she’s essential, whether the government does or not, and she knows she has no other choice.