It’s said the coronavirus does not discriminate. But anecdotal accounts, research and reports of frontline worker deaths in the UK suggest that assertion could be off the mark.

Across the nation, tributes have been flooding in for health workers who reportedly died from coronavirus-related complications. Some of them came from minority black or Asian communities, according to media reports.

On Saturday, Health Secretary Matt Hancock addressed the fact that a number of health workers who have died from coronavirus were from “minority ethnic backgrounds,” saying on BBC Breakfast he found it “really upsetting.”

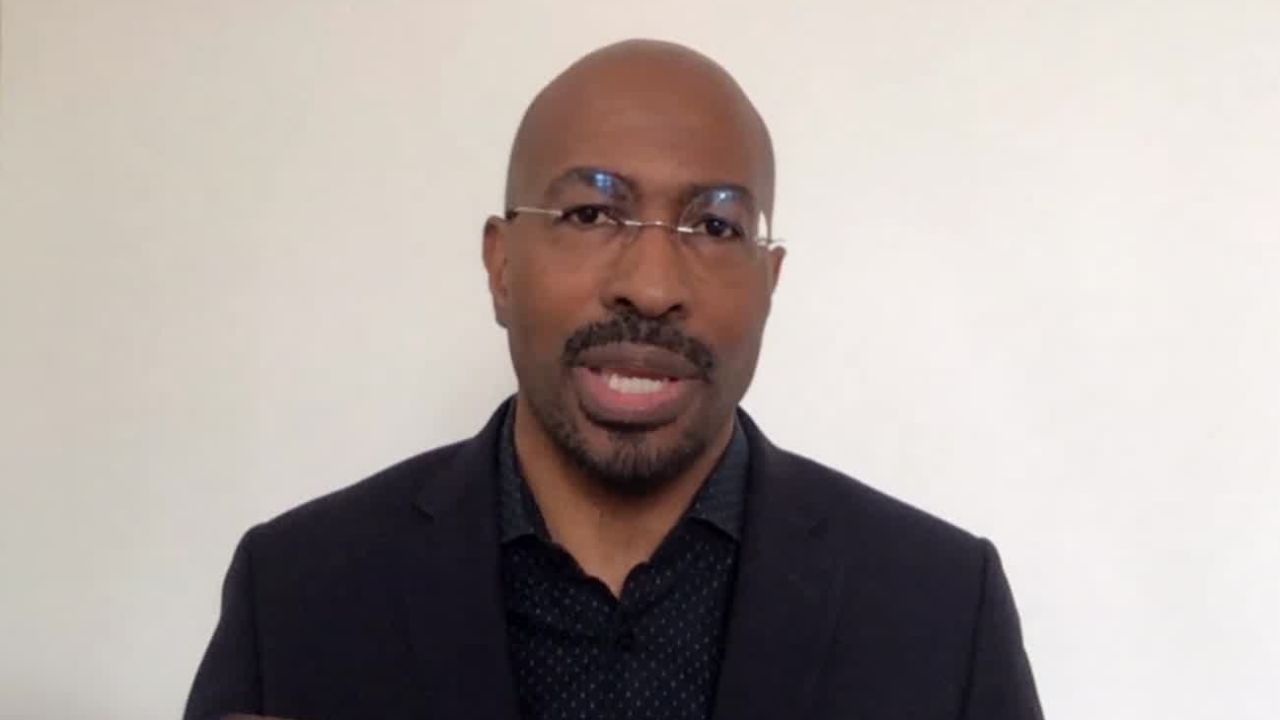

In an interview with the British daily The Guardian, the head of the the doctors’ union, the British Medical Association (BMA), called for a government investigation into whether minorities were more vulnerable to Covid-19.

“At face value, it seems hard to see how this can be random,” Dr. Chaand Nagpaul said in reference to the first 10 doctors in the UK to be named as having died from coronavirus-related symptoms coming from minority backgrounds, according to The Guardian.

Read more:

“We have heard the virus does not discriminate between individuals but there’s no doubt there appears to be a manifest disproportionate severity of infection in BAME [black and minority ethnic] people and doctors. This has to be addressed – the government must act now,” he told The Guardian.

Covid-19 has ripped through families and grounded the UK economy, and questions are mounting in the British media as to whether it is having a disproportionate effect on minority groups in Britain.

But unlike the US – where data released by Chicago and Michigan authorities showed a clear racial disparity in coronavirus victims – the picture is not that clear in the UK. Experts say there are many unknowns: mainly that British health authorities are not reporting race in statistics on confirmed cases or fatalities.

This public data deficit has not only left communities in the dark, it has failed to highlight the structural inequalities or health factors that might be at play behind the mounting deaths: be it geography, poverty or genetic disposition.

“The UK ought to be good at collecting data,” Sunder Katwala, the director of British Future, a think tank that focuses on identity, told CNN.

Experts say Britain has a strong tradition of research on the social determinants of health and health inequalities, and is among the few countries in Europe that collects race data.

But officials dropped the ball in making that information public, Katwala said. “I think with the sheer pressure of this crisis – of realizing how big it is and the economic impacts – it feels like policymakers have been slightly slow to work on this dimension.”

The National Health Service (NHS) has been collating race and socio-economic information from Covid-19 cases, Sarah MacLennan, NHS England spokesperson told CNN. Data teams will then look at how “socio-economic aspects and housing conditions” affect the spread of the virus, she said.

No timeline was provided on when those data points would be released to the public.

On Friday, the UK had the fifth highest number of coronavirus-related deaths in the world, with 8,958 fatalities and 74,605 confirmed cases, according to Johns Hopkins University figures.

First signs

Early research this month by Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC), into confirmed Covid-19 cases admitted to critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, indicates that ethnic minorities may be over-represented when compared to the general population. The data is not from all critical care units in those regions.

Figures released on April 10 found that as many as a third of 3,370 coronavirus patients receiving critical care came from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) backgrounds – nearly three times the 13% proportion of ethnic minorities in the UK population, according to the 2011 census.

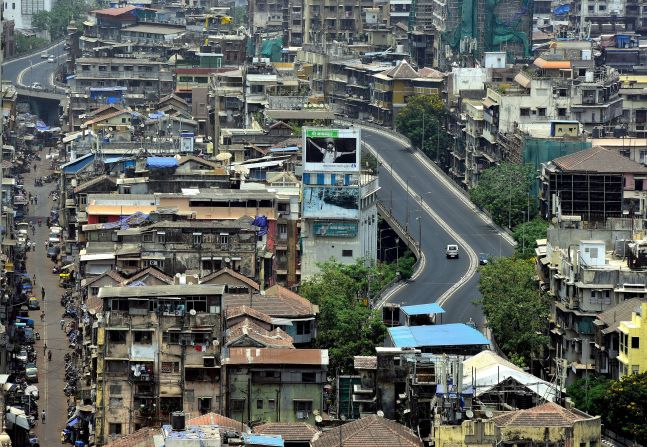

The virus has been hitting urban centers the hardest, where most of the critical care data has been coming from. In England, Sheffield has the highest number of confirmed cases per 100,000 of the population, followed by London, Liverpool and Birmingham, according to Public Health England data analyzed by urban policy charity The Centre for Cities.

These are cities that have large minority populations, suggesting that geography has left minorities even more exposed.

Studies show these communities, particularly people of Asian backgrounds, “have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and high blood pressure, which has been shown in China and Italy [Covid-19 cases] to be associated with more severe disease,” University of Leicester professor Kamlesh Khunti told CNN.

Black people of West African descent also have an increased risk of strokes and hypertension, conditions that can exacerbate coronavirus symptoms, compared to the general population, according to Keith Neal, emeritus professor of the Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases at the University of Nottingham.

Britain’s ethnic minority population is in general younger than Britain’s white population, according to a report by the Centre for Policy on Ageing.

Knowing that the virus typically affects older people more seriously, comparing ICNARC’s findings to the over-65 population of each minority group could make “that figure [of disproportionality] even worse,” Neal added.

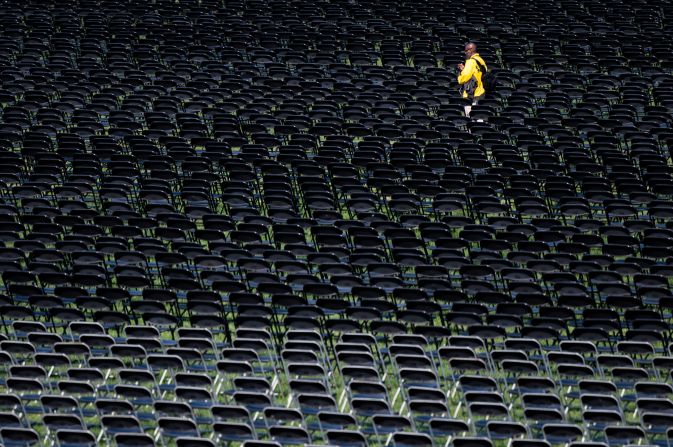

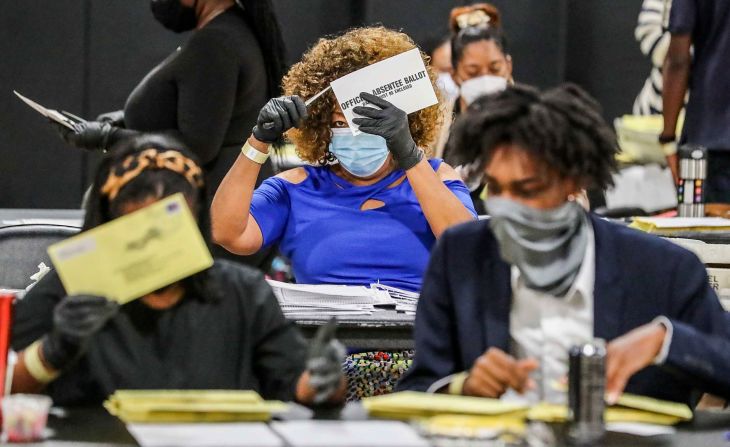

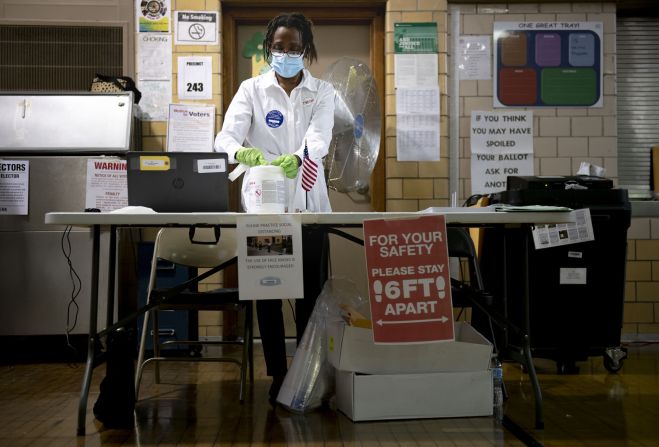

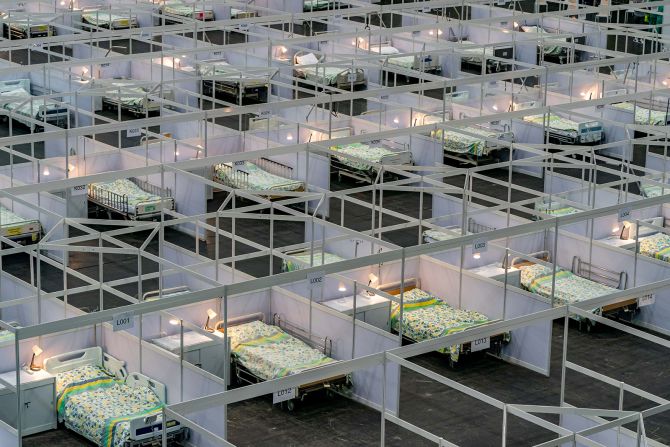

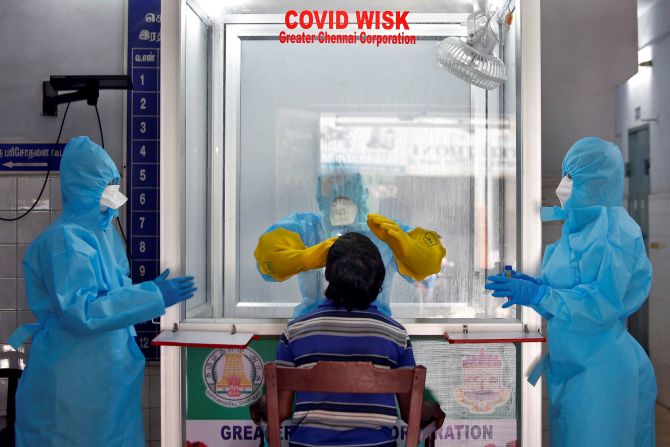

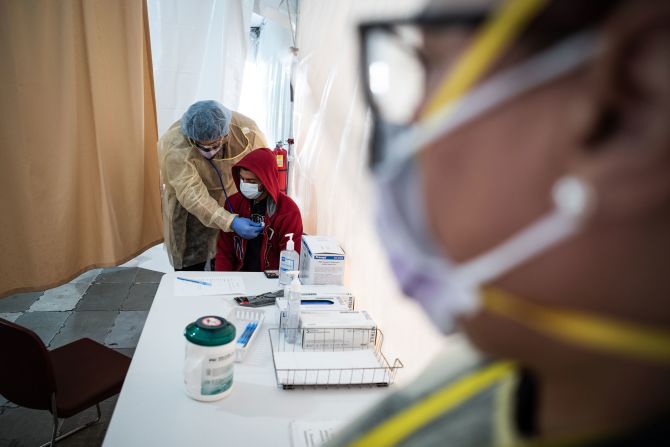

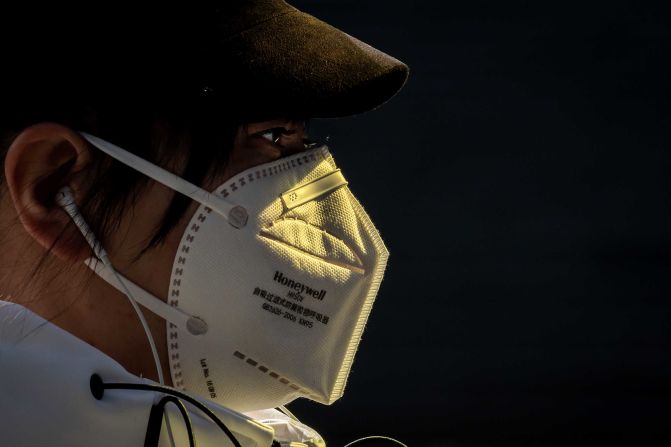

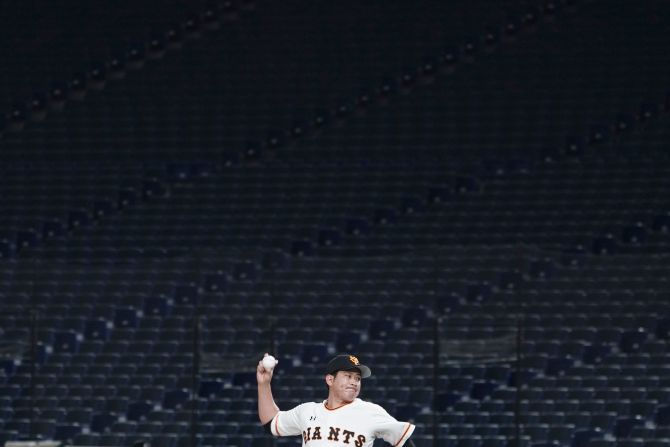

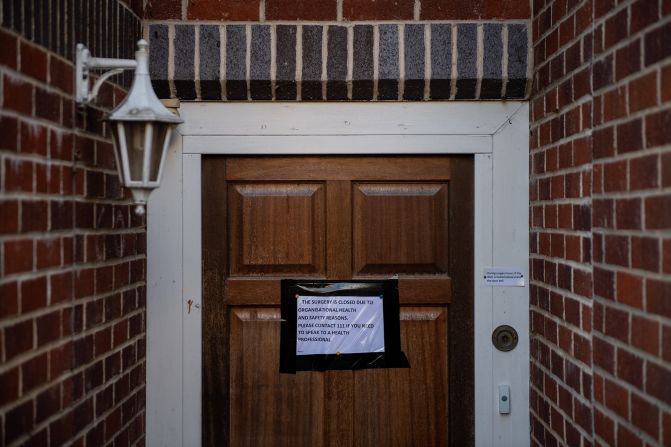

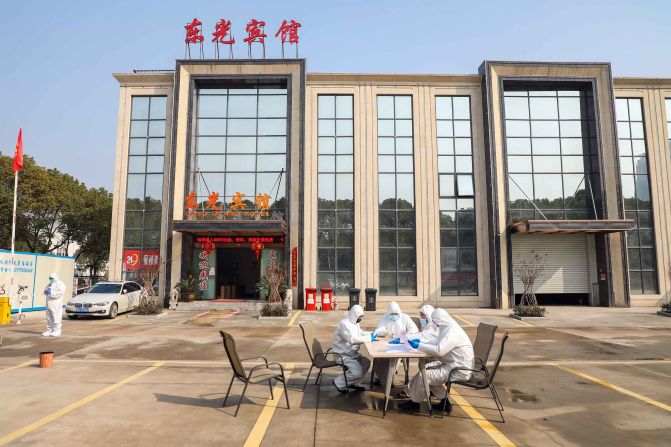

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

Poverty linked to poor health

These danger signs also point to long-standing structural inequalities in Britain. “Members of minorities in Britain are more likely to be living in poverty, they’re more likely to be in overcrowded houses,” Kate E Pickett, a professor of Epidemiology at the University of York and co-founder of the Equality Trust, told CNN.

“So there are the reasons why the spread might be happening more rapidly in those groups where their baseline health is worse” and their ability to social distance is low, she said.

Zubaida Haque, the deputy director of the race and equality think tank Runnymede Trust, said, “It’s not your race, per se, which makes you vulnerable to Covid-19.

“It’s what your experience of being that color or ethnicity means, in terms of health outcomes and we know through a government commissioned review that if you are poorer, have high rates of child poverty, have insecure work – all of those factors are linked to poor health outcomes,” she said.

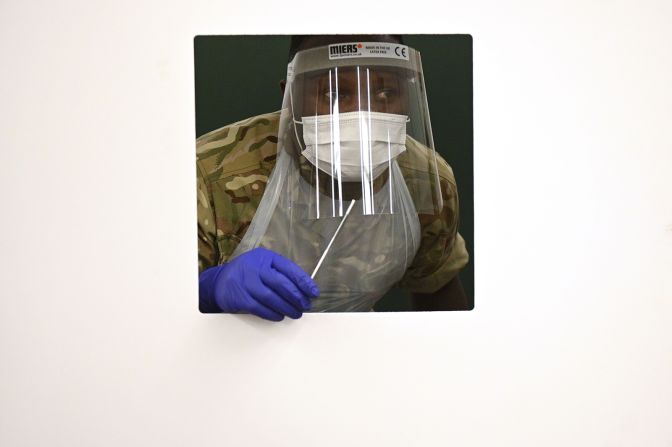

As deaths mounted in the UK, it became clear that people of color had become foot soldiers in the fight against the virus. Nearly half of medical staff employed by the NHS come from minority backgrounds, and nearly a third of doctors are immigrants.

That includes Ear, Nose and Throat consultant Dr. Amged el-Hawrani, health care assistant Thomas Harvey and Dr. Alfa Sa’adu, who died from coronavirus-related complications.

Harvey’s daughter Tamira alleged that London’s Goodmayes Hospital failed to provide necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) to her father. And just a few days before Harvey’s death, emergency services “refused” to come to take him to hospital, Tamira said, despite family concerns that he wasn’t “breathing properly.”

The NHS trust responsible for the hospital where Thomas Harvey worked told CNN that there were no symptomatic patients when he went off work sick and that it has been following national PPE guidance. The London Ambulance Service did not respond to his daughter’s allegations that they “refused” to come once.

Cultural factors

Cultural factors could have also come into play. “One explanation to why Italy was badly hit is it had more of a culture of multigenerational family living households,” Katwala said, a trend “more true of some minority communities in the UK than the general population.”

In Derby, a multiracial city of nearly 250,000, local Nazir Hussain said announcements of coronavirus-related deaths have become a daily occurrence among its Asian population.

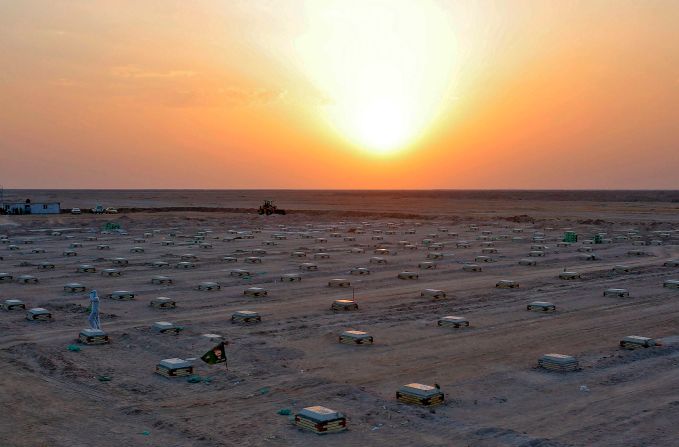

Hussain, a committee member at Derby Jamia Mosque said the community was braced for the worst, and had prepared 300 graves in the event of more deaths. The fear is the older generation, many of whom live in big multigenerational households, may be more vulnerable to the virus, he said.

Dominic Rech and Martin Goillandeau contributed to this report.