When Declan Chan arrived in Hong Kong from Zurich on March 17 after six weeks overseas, city officials made him put on a plain-looking white wristband and download an app called StayHomeSafe before he exited the airport.

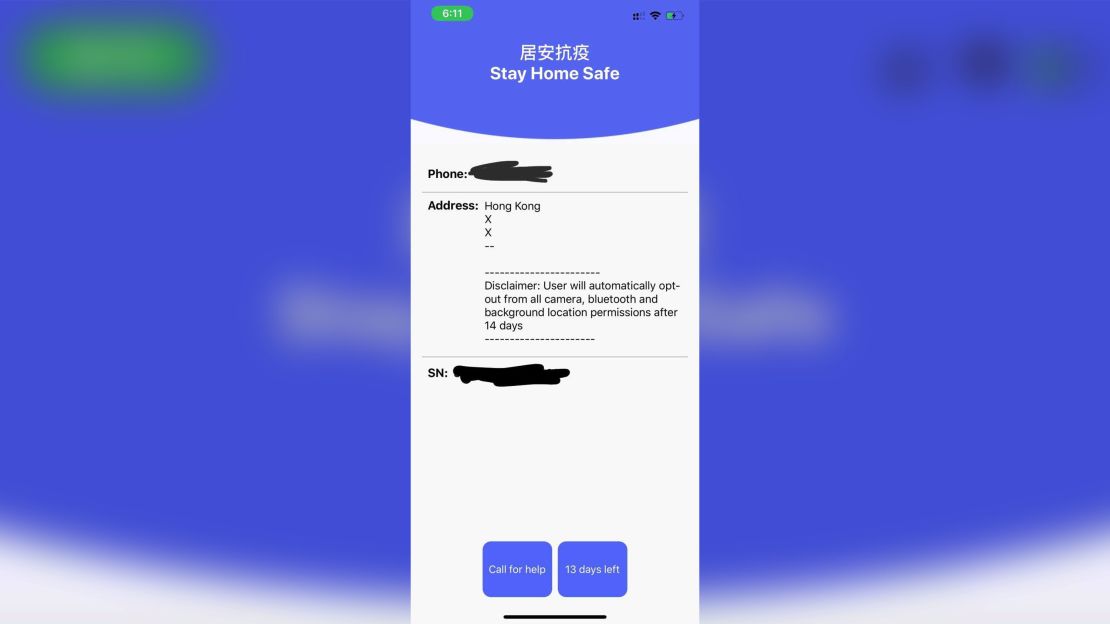

He was told to register on the app once he got home, which would start a 14-day countdown, and walk to all four corners of his apartment so it could capture the location and confines of his home.

As countries around the world fight the spread of the coronavirus, several governments are using technology to monitor quarantines — particularly of people coming in from overseas. Israel this week approved the use of cellphone tracking technology to monitor suspected coronavirus patients — an option normally used only for counterterrorism. Thailand is reportedly giving all new arrivals at its airports a free SIM card and making them download an app that tracks their location for 14 days.

But there are concerns that tracking measures to contain the pandemic could pave the way for greater government surveillance. In Israel, for example, Opposition politicians and constitutional experts criticized the tracking measures, not only for their invasion of privacy but also for the lack of parliamentary oversight in pushing them through.

The urgency to fight the coronavirus could open up a new front in the long-running global debate between privacy and security. Over the years, some governments have relied on controversial practices such as using facial recognition and phone data collection to protect citizens, potentially at the expense of their personal privacy.

“I think the question might be whether the means justify the ends,” Jennifer King, director of privacy at Stanford University’s Center for Internet and Society, told CNN Business. “I’d want to hear a clear justification as to why some of the requests for personal data are being made, and why other methods might not work as well or reasonably well without the privacy impact.”

Chan’s wristband is one of 60,000 that Hong Kong is deploying to enforce quarantines and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. The wristband and the app were developed in collaboration with a local startup “to ascertain people under quarantine are staying at their dwelling places,” according to a government statement.

Chan, 36, said he wasn’t explicitly told what would happen if he took off the wristband or disconnected the app. A form he was given – a photo of which he shared with CNN Business – says that anyone who “contravenes or knowingly gives false information to [the] Department of Health” is liable to face a 5000 HKD ($644) fine and six months in prison.

“Should the app be deleted during quarantine period, the Department of Health and the police will be alerted to take follow-up action,” a Hong Kong government spokesperson told CNN Business. The spokesperson said users are free to delete the app after 14 days.

The governments have painted the quarantine tracking and monitoring as necessary steps to curb the virus, while also insisting they are committed to protecting privacy.

“The [Hong Kong government] attaches great importance to privacy protection,” the spokesperson said, adding that its tracking app does not collect any additional data from the users’ smartphone. “The collection of personal data is minimal in accordance with the provision of the quarantine order.”

Israel’s deputy attorney general, Raz Nizri, said tracking people is “essential” to save lives. “The aim was to find the optimal solution that will minimize the infringement of privacy,” he told Kan Reshen Bet radio.

Thai authorities will delete user data collected by their tracking app within 14 days, an official at the country’s telecommunications authority told the Bangkok Post newspaper.

Experts say that while some amount of tracking may be necessary to contain the virus, users need to be protected from it being turned into a broader surveillance tool.

“Mandatory orders or those with no explicit restrictions on the collection and use of the data would be very worrisome,” said King.

There is also the risk that measures seemingly justified by the current pandemic could be retained or expanded even after they are no longer necessary.

“I think we have to be on the lookout for ‘scope creep’ — contexts where we demand emergency powers that risk privacy and then fail to walk back after the emergency passes,” she said.

The US government is also in discussions with the tech industry to use Americans’ location data to track the spread of the coronavirus, with Google (GOOGL) and Facebook (FB) confirming they are exploring ways to share aggregated, anonymized data rather than location data of specific users, a point they took great pains to emphasize. But larger Western democracies will likely face bigger challenges and greater pushback in trying to institute some of the tracking measures other countries have.

“Every country is different, and I think that the incentive to engage in this sort of tracking is higher for smaller countries that have dense populations and the political will and technology necessary to make this happen — like Israel and Hong Kong,” said Dipayan Ghosh, a former Facebook and Obama administration official who is now a fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. “It is difficult to imagine these policies extending to Western democratic countries at this time.”

Chan said he preferred being forced to quarantine at home rather than being placed in a government facility.

“I kind of feel weird that there’s no other option, other than the bracelets. I do feel a bit weird,” he said. “But it’s the lesser of the two evils, if I have to choose between this and a quarantine camp… at least home is a safer environment.”