Passing through airports in Hong Kong and Tokyo this week highlighted the differences in the approaches of the two Asian hubs in dealing with the novel coronavirus pandemic.

Upon arrival at Hong Kong International Airport on Sunday, after disembarking directly onto the tarmac we were taken to a quarantine area on the lower level of the airport.

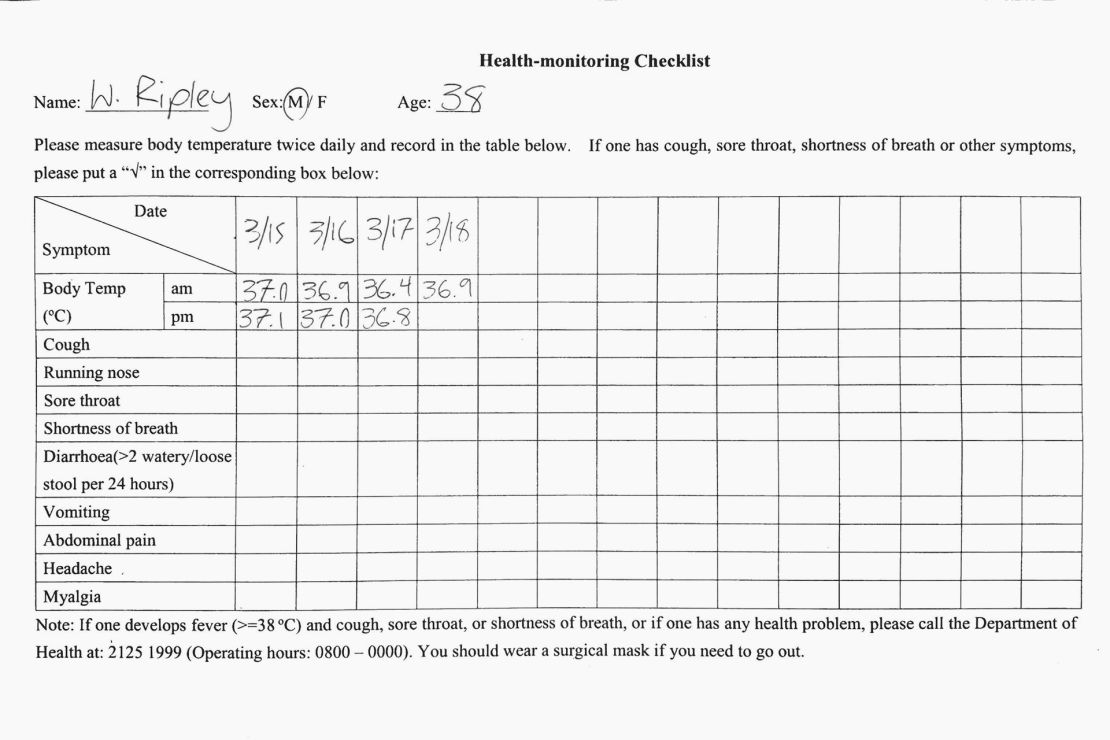

There we underwent multiple health and security checks. My temperature was taken, I filled out a detailed questionnaire indicating I had not traveled to China, Italy, South Korea, or other coronavirus hotspots.

Two quarantine officers gave me a checklist of instructions for after I left the airport, including that I take my temperature twice daily and immediately report any abnormal symptoms to the Department of Health.

If I was to land in Hong Kong today, it would be even stricter.

The local government announced this week that anyone arriving from a foreign country is required to self-quarantine for two weeks, and will likely be issued an electronic monitoring bracelet that will alert the authorities if they leave their home or hotel.

So far, Hong Kong’s intense measures appear to be containing the spread of the virus.

Despite Hong Kong sharing a border with mainland China, the number of cases in the densely populated city remains at 167– although the city has seen a spike in cases this week, mostly imported by international travelers arriving from countries struggling to deal with the virus.

Beyond the airport, it’s hard to spot someone in Hong Kong not wearing a mask. The city clearly learned painful lessons from the SARS outbreak of 2003, when some 300 Hong Kong citizens died.

Hong Kong acted early closing schools, public libraries and museums, and urging people to work from home, way back in February when it had relatively few cases. While the government didn’t go so far as to close bars and restaurants, when the virus arrived in Hong Kong many people took it upon themselves to stay home and avoid crowds.

Nobody is taking any chances. In Tokyo it’s very different.

Japan contrast

When I arrived at Narita airport in Japan this week our plane pulled up to the gate as usual.

I walked freely through the airport, more than 500 meters to the quarantine office where about 10 quarantine officers hastily tried to process everybody who came from my flight.

Nobody took my temperature, although I did walk past a thermal camera scanning for elevated body temperatures. But it was a cold evening and many passengers were bundled up in coats that could have hindered the camera’s ability to get an accurate reading.

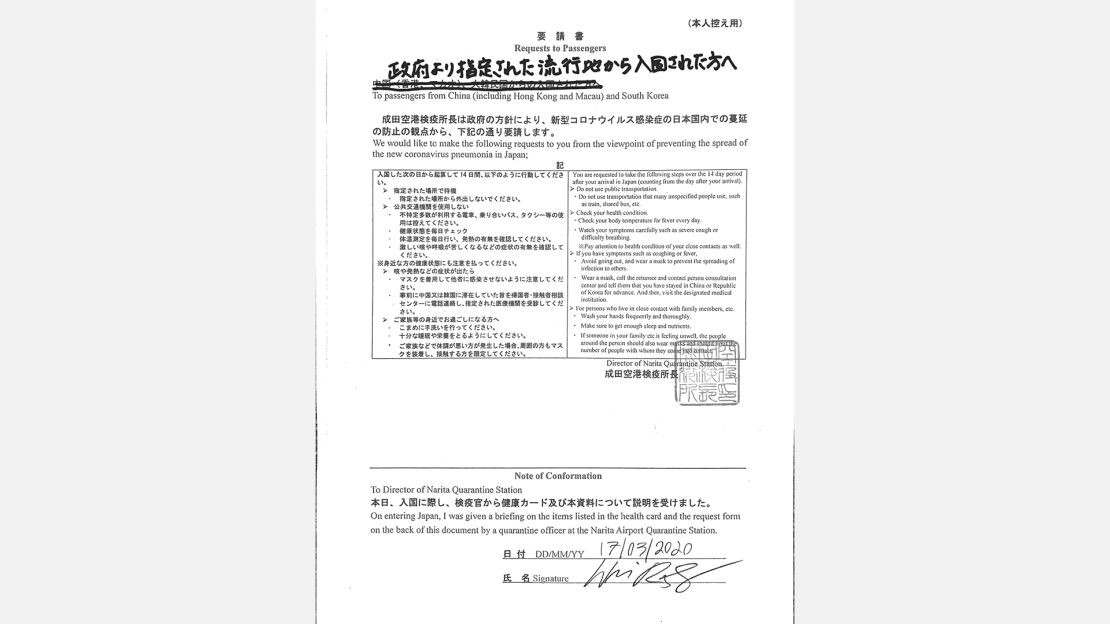

My quarantine officer gave me forms to sign in English requesting that I remain in my home for 14 days, check my temperature daily, and avoid public transportation.

These were simply requests, and are not being enforced. I am following the suggested protocol, but there is nothing to stop me from going anywhere I please.

Other countries have declared a state of emergency and gone into lockdown, but Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has said the situation in Japan does not yet warrant his use of emergency powers.

In Tokyo, while many schools are closed, some large gatherings are canceled, and an unprecedented number of people are working from home, most bars and restaurants are open, lots of people are using crowded public transport, and parents still take their children outside to play, usually without masks. There is plenty of toilet paper on supermarket shelves.

In explaining why Japan is not on lockdown, Abe points to Japan’s relatively small number of confirmed cases, compared to other countries.

It’s true the island nation of 125 million people has 873 confirmed cases, compared to 31,506 in Italy, 16,169 in Iran and 8,413 in South Korea.

But there is a key difference between Japan and other nations with a skyrocketing infection count: Japan is testing a tiny fraction of people compared to many other countries.

By March 17, Japan tested just 14,525 people, according to the Ministry of Health, although some of those people had been tested multiple times. By contrast, South Korea – a country that has managed to stabilize a huge outbreak – can test about 15,000 people a day.

Japanese officials have said the country will ramp up its testing capacity to 8,000 people per day by the end of the month.

For an aging society, a significant and rapid spread of coronavirus could have a devastating impact.

Widespread testing is the only way to know for sure if the calm in Tokyo is a true picture of the coronavirus situation in Japan – or if it is actually the calm before the storm.