Michelle Kunimoto has a knack for finding exoplanets, or planets that orbit stars outside of our solar system.

The University of British Columbia astronomy student found four while she worked on her undergraduate degree.

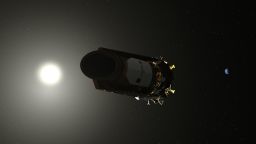

Now a doctoral candidate, she has discovered an additional 17 planets by poring over data from NASA’s Kepler mission, which ended in 2018.

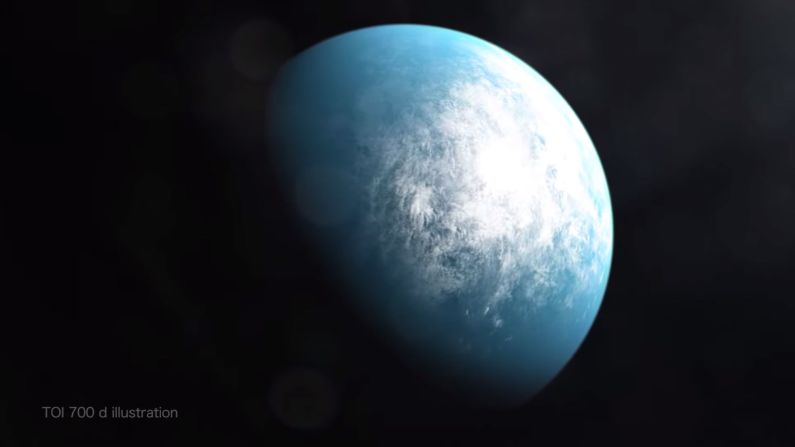

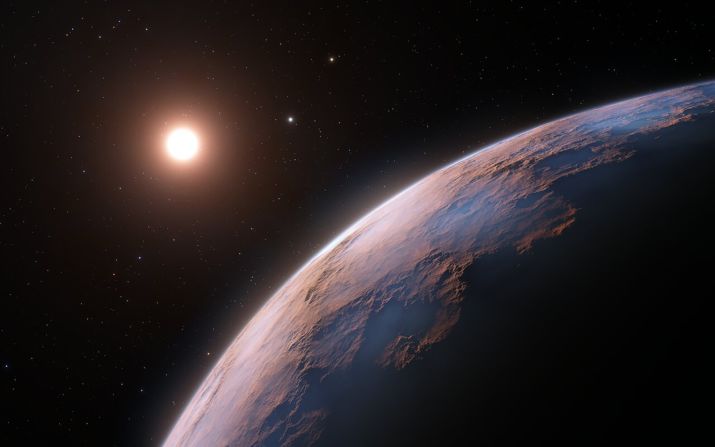

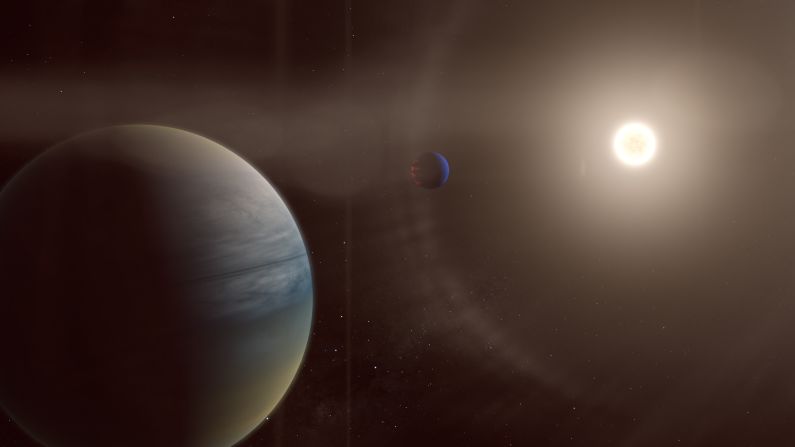

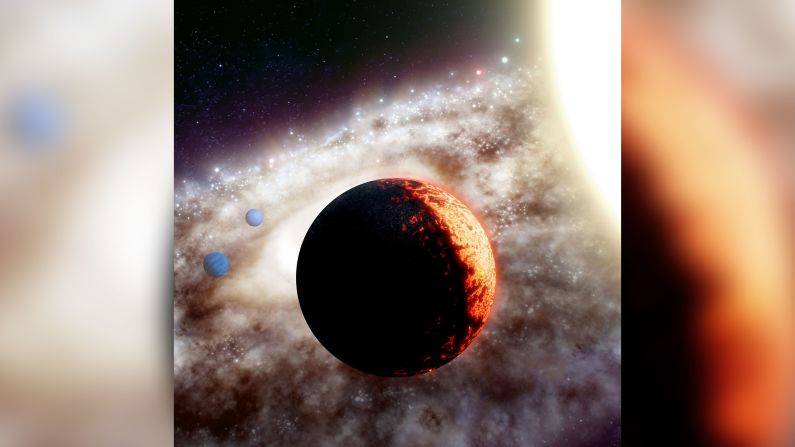

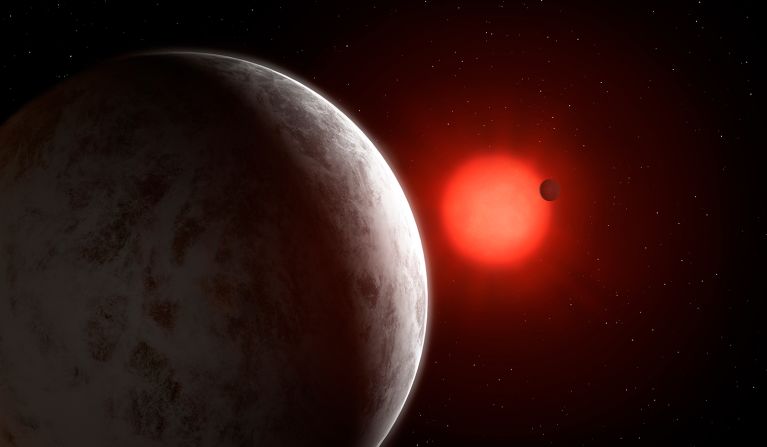

One is found within the habitable zone of its star. The distance allows for temperatures and conditions that could be right for liquid water – and life – to be on the surface. Potentially habitable exoplanets are of particular interest to Kunimoto and her research.

A study including her findings was published Thursday in The Astronomical Journal.

“This planet is about a thousand light years away, so we’re not getting there anytime soon!” said Kunimoto in a statement. “But this is a really exciting find, since there have only been 15 small, confirmed planets in the Habitable Zone found in Kepler data so far.”

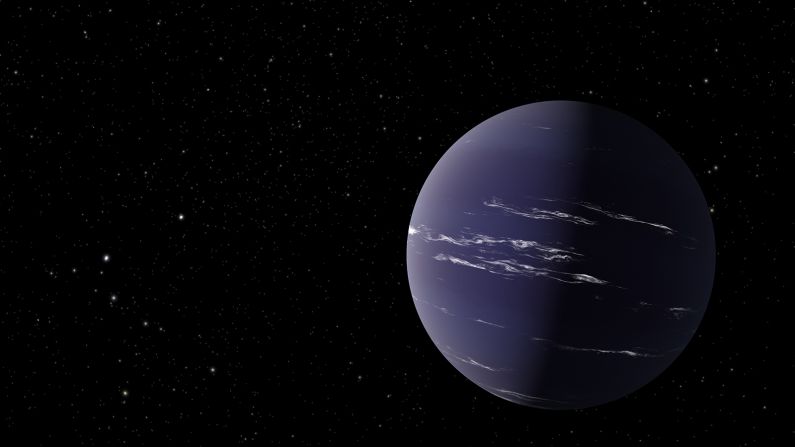

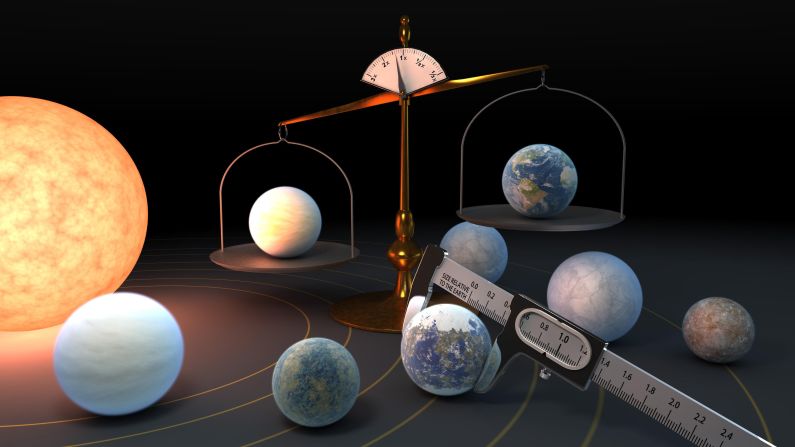

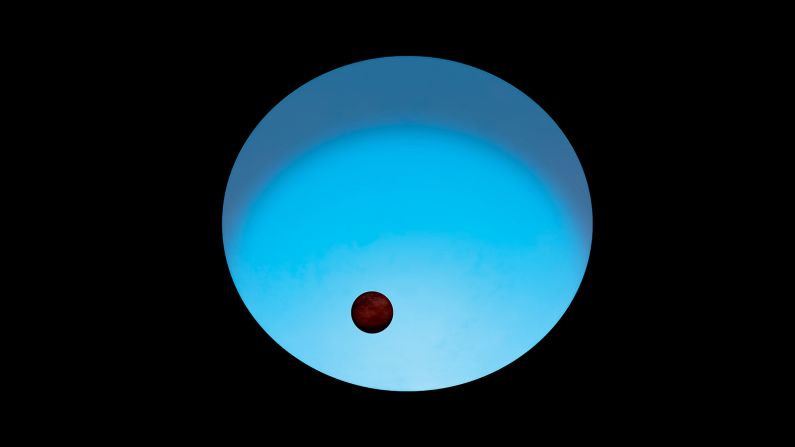

The exoplanet, known as KIC-7340288 b, is about 1.5 times the size of Earth, probably rocky like our planet and not gaseous.

A year on this planet takes around 142.5 Earth days, and it’s orbit is slightly larger than Mercury’s path around our sun. It receives a third of the light our own planet receives from the sun.

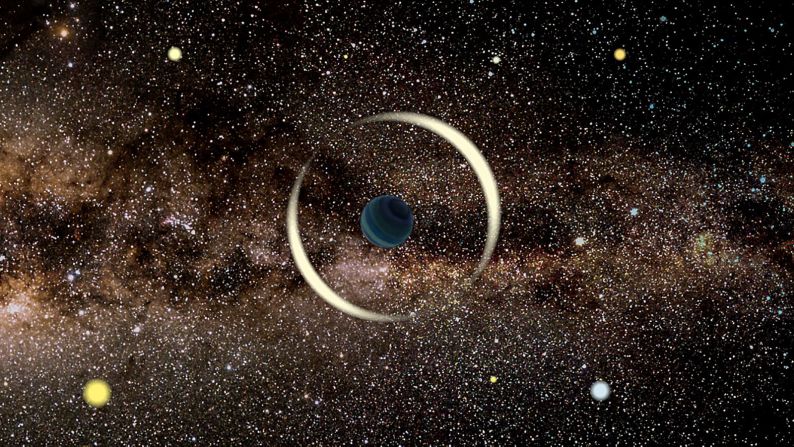

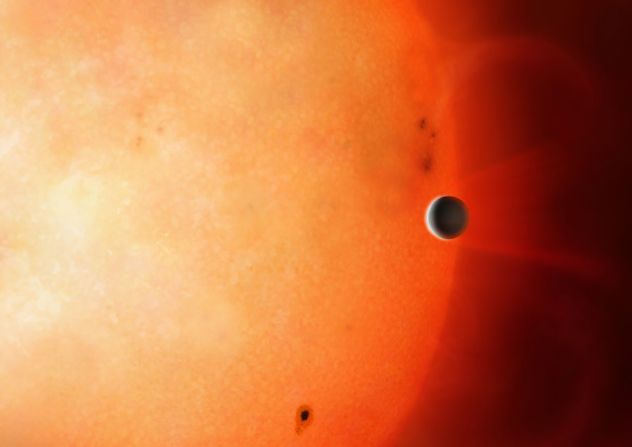

Kunimoto found it and the 16 others using the transit method when looking at NASA’s Kepler mission data.

“Every time a planet passes in front of a star, it blocks a portion of that star’s light and causes a temporary decrease in the star’s brightness,” Kunimoto said.

“By finding these dips, known as transits, you can start to piece together information about the planet, such as its size and how long it takes to orbit.”

Most of the other planets Kunimoto found were significantly larger than Earth – as much as eight times. The smallest just two-thirds and one of the smallest found by Kepler yet.

Although the Kepler mission ended in 2018, data collected during the planet-hunting spacecraft’s nine years will fuel research by astronomers for years to come. Once in space, it stared at the same patch of sky for years, allowing astronomers to search for exoplanets around stars.

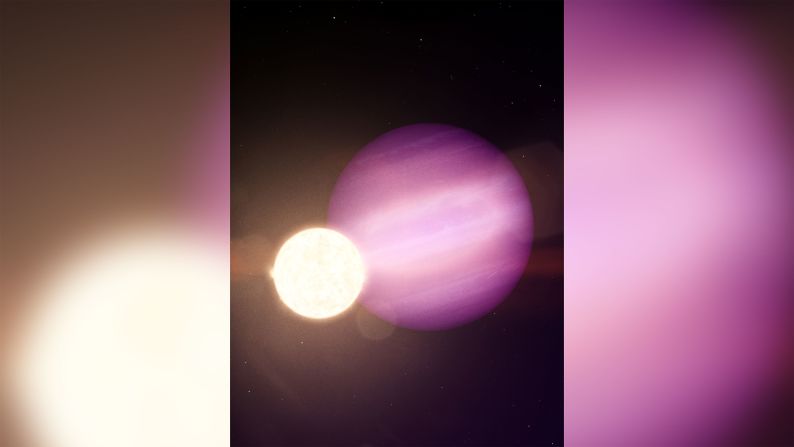

During the mission, Kepler discovered 2,899 exoplanet candidates and 2,681 confirmed exoplanets in our galaxy, revealing that our solar system isn’t the only home for planets.

Kepler also allowed astronomers to discover that 20% to 50% of the stars we can see in the night sky are likely to have small, rocky, Earth-size planets within their habitable zones – which means that liquid water could pool on the surface, and life as we know it could exist on these planets.

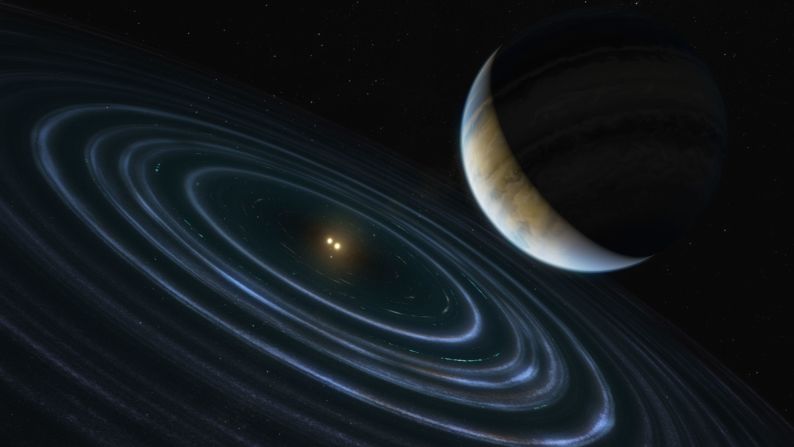

Kunimoto conducted a follow-up investigation of the planets she found in the data with fellow university alumnus Henry Ngo a Ph.D. candidate at the California Institute of Technology.

“I took images of the stars as if from space, using adaptive optics,” she said. “I was able to tell if there was a star nearby that could have affected Kepler’s measurements, such as being the cause of the dip itself.”

They made observations using the Gemini North 8-meter Telescope in Hawaii and its Near InfraRed Imager and Spectrometer instruments, allowing for a sharp, detailed look to follow up on their findings in the data.

Next up for Kunimoto: taking a closer look at the known exoplanet census collected by Kepler so far and looking for more planets within the habitable zone.

“We’ll be estimating how many planets are expected for stars with different temperatures,” said Jaymie Matthews, Kunimoto’s doctoral supervisor.

“A particularly important result will be finding a terrestrialHabitable Zone planet occurrence rate. How many Earth-like planets are there? Stay tuned.”