The more scientists learn about exoplanet K2-18b, the more intriguing it becomes. And it could broaden the types of exoplanets astronomers target in their search for life beyond Earth.

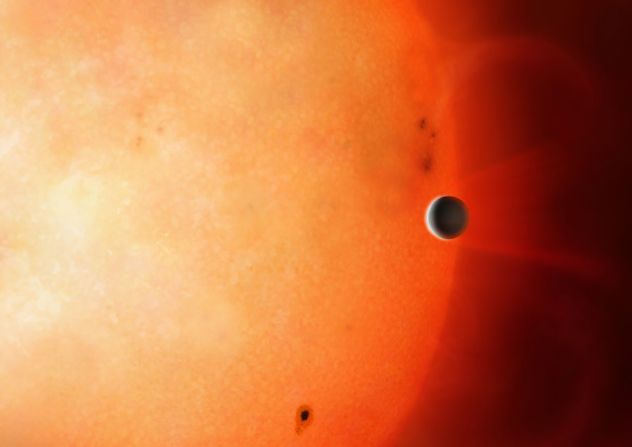

Last year, astronomers peered into the atmosphere of the exoplanet – a planet outside our solar system – and discovered both water vapor and temperatures that could potentially support life.

Now, astronomers have used data about the exoplanet, including its mass, radius and what they learned about the atmosphere, to determine if it can host liquid water on its surface. Their study published Wednesday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

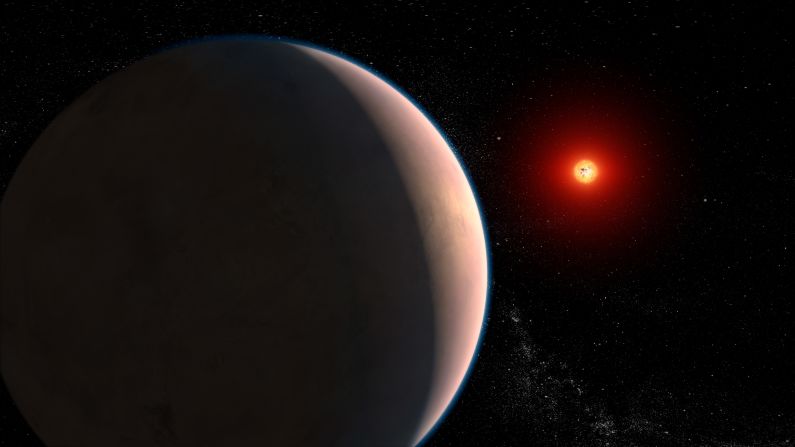

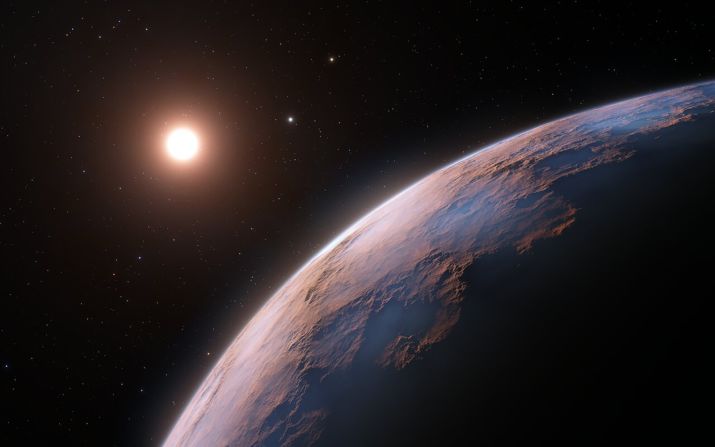

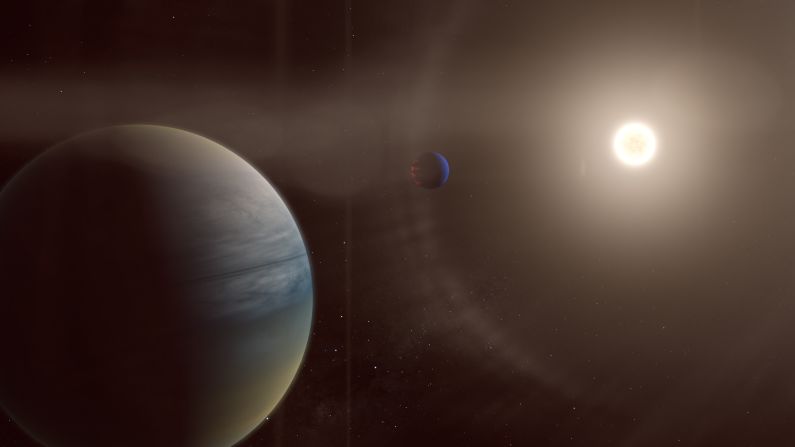

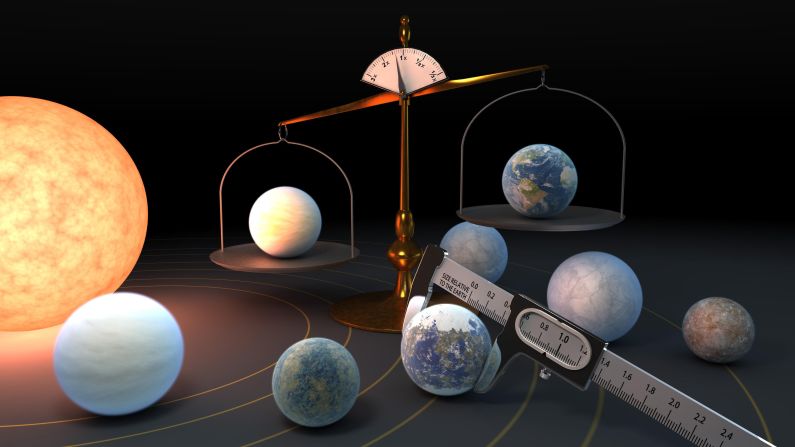

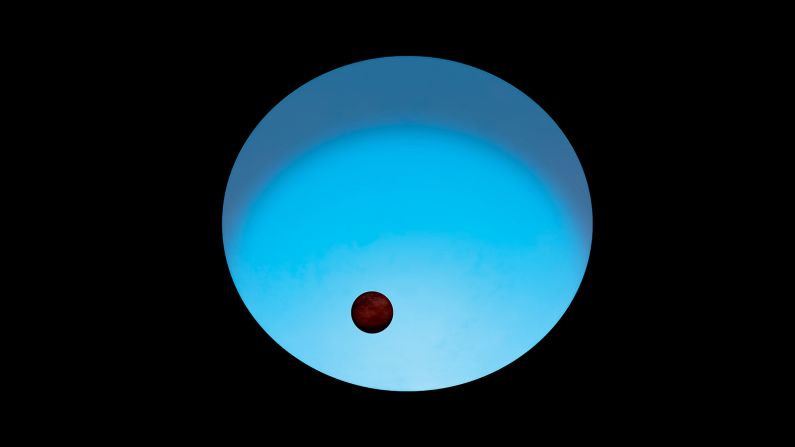

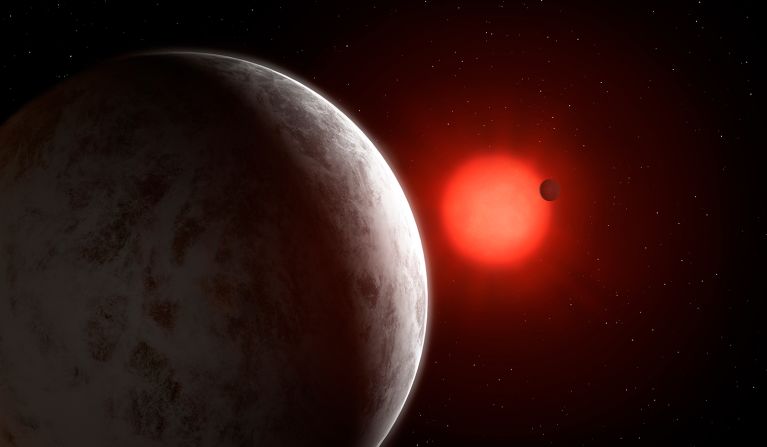

K2-18b is eight times the mass of Earth and orbits a red dwarf star 124 light-years away from Earth in the Leo constellation. The planet was first discovered in 2015 by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft.

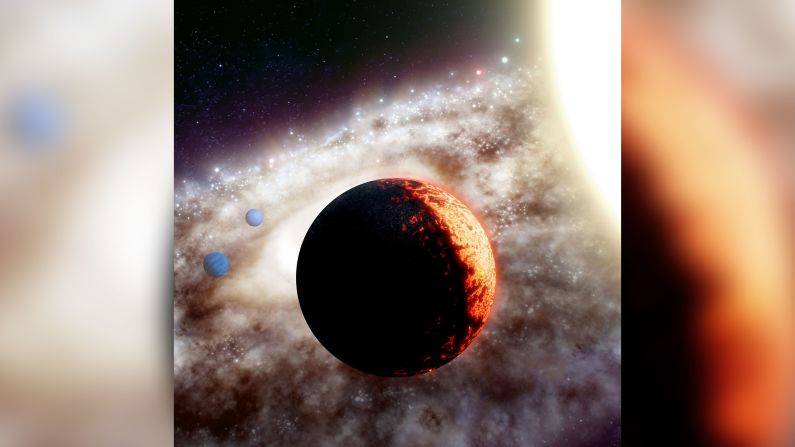

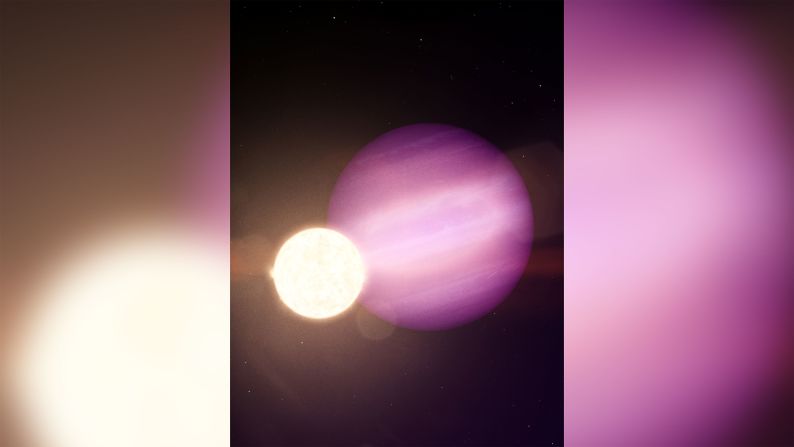

The exoplanet completes one orbit around its star every 33 days and it’s much closer to its star than Earth is to the sun. But the red dwarf star is also much cooler than our sun. The red dwarf star is an active one, however, which is likely exposing the exoplanet to more radiation than Earth receives.

“Water vapour has been detected in the atmospheres of a number of exoplanets but, even if the planet is in the habitable zone, that doesn’t necessarily mean there are habitable conditions on the surface,” said Nikku Madhusudhan, lead study author from the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, in a statement. “To establish the prospects for habitability, it is important to obtain a unified understanding of the interior and atmospheric conditions on the planet – in particular, whether liquid water can exist beneath the atmosphere.”

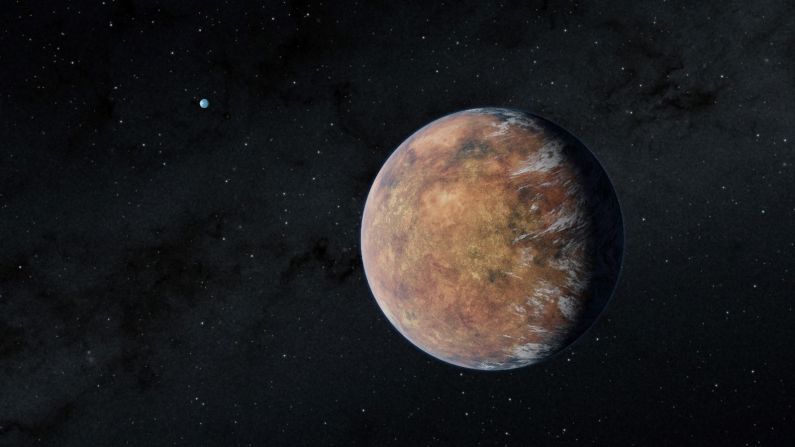

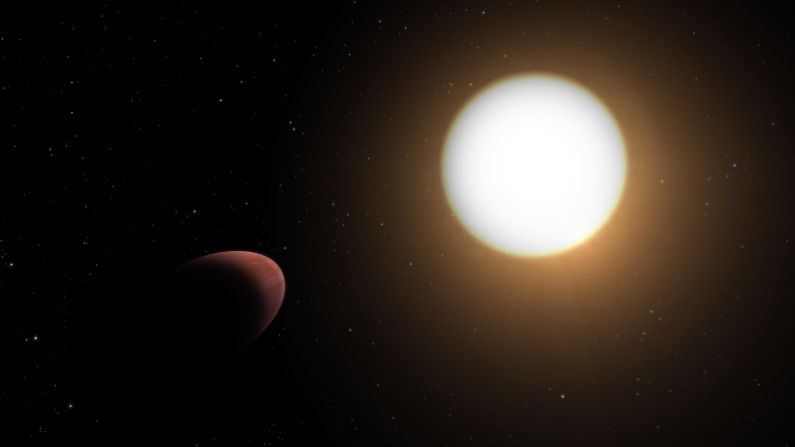

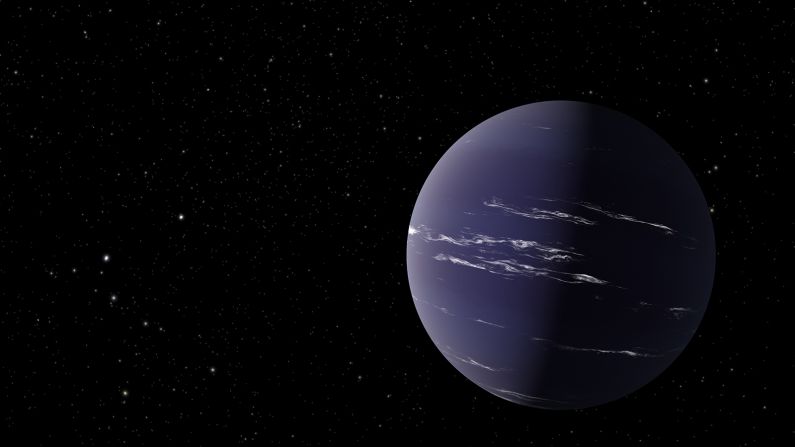

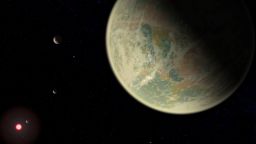

Based on its size, the exoplanet could be a Super-Earth or a mini-Neptune because it’s double the size of Earth but not as large as Neptune. And it’s within the habitable zone of its star, or the right distance from the exoplanet to the star that means liquid water can exist on the planet’s surface.

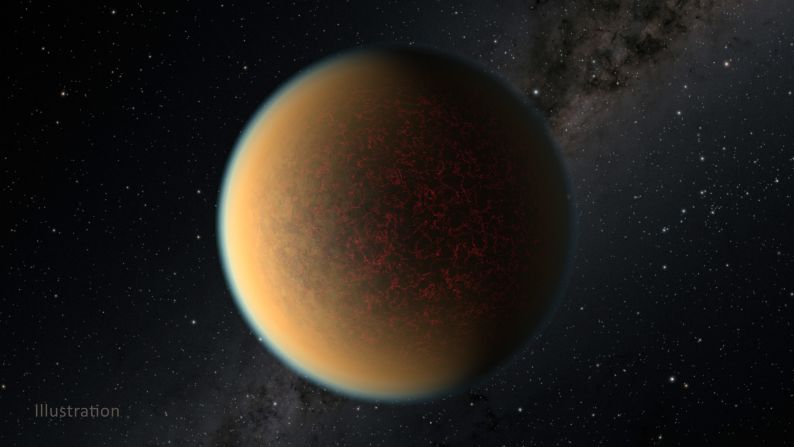

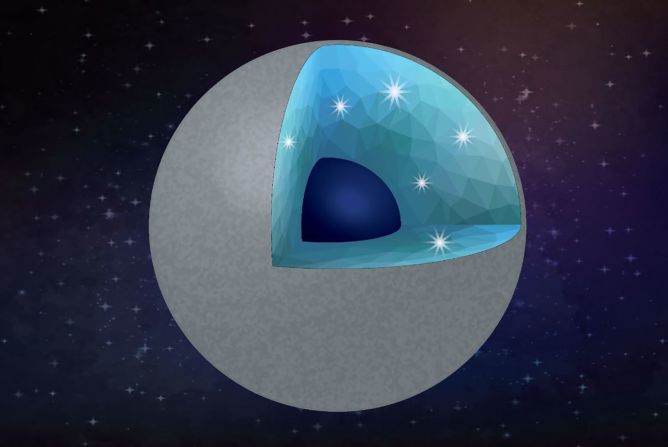

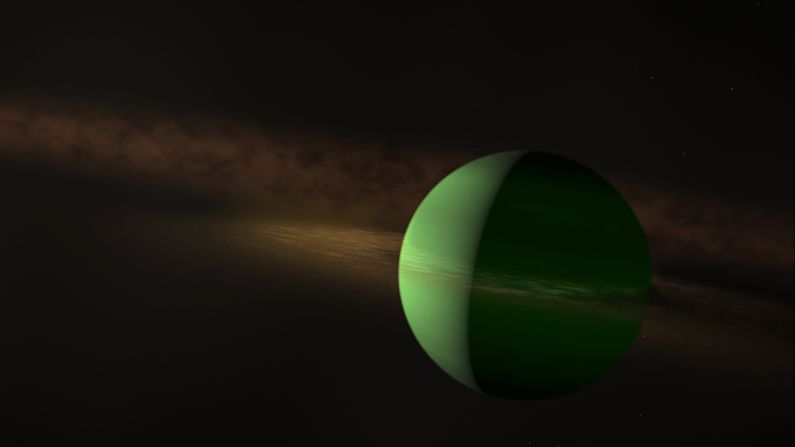

Although the atmosphere contains water vapor, it’s also rich in hydrogen. If the exoplanet is a mini-Neptune, it may also include a significant hydrogen “envelope” or layer around a high-pressure water layer. If this hydrogen layer is too thick, it would increase the exoplanet’s temperature and pressure, making it inhospitable.

The research team looked over the available atmospheric data to determine that the amount of detectable water vapor is significant, while other chemicals like methane and ammonia were lower than expected.

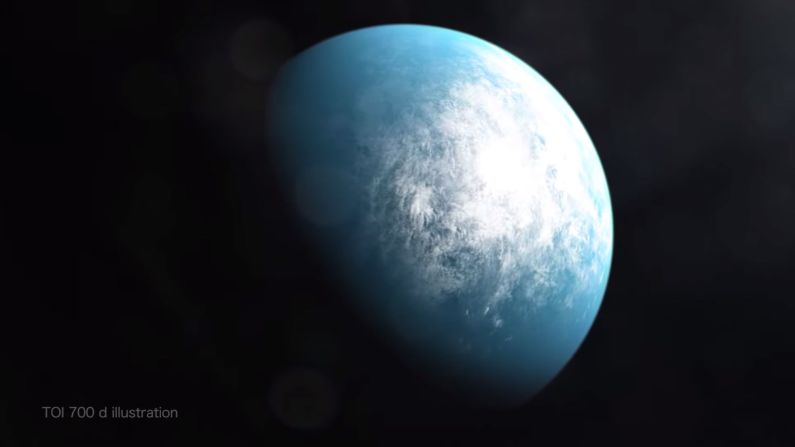

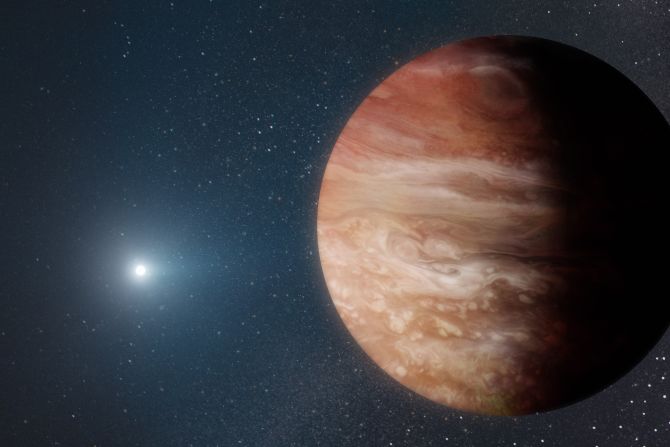

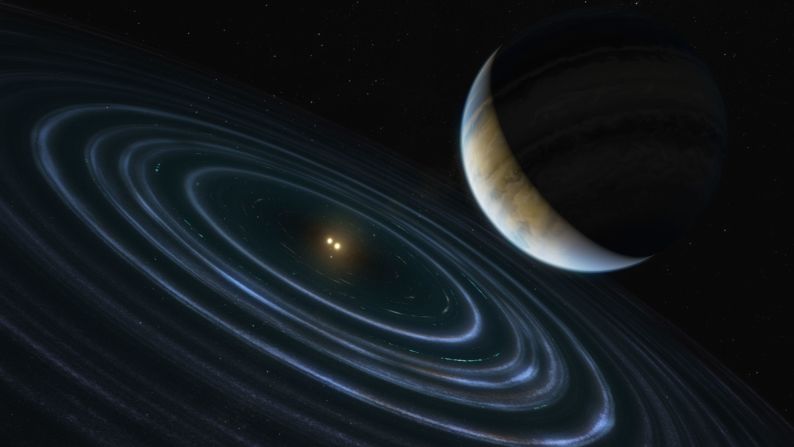

This allowed them to create boundaries for a model to simulate the planet and its interior. They came up with numerous possibilities. The planet could be a rocky world larger than Earth, a gaseous mini-Neptune or even an ocean world. In the case of a water world, the model would allow for pressures and temperatures similar to Earth’s oceans.

“We wanted to know the thickness of the hydrogen envelope – how deep the hydrogen goes,” said Matthew Nixon, study co-author and a PhD student at the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy. “While this is a question with multiple solutions, we’ve shown that you don’t need much hydrogen to explain all the observations together.”

They found that the most the hydrogen envelope would account for is 6% of the planet’s mass, and the minimum would be one-millionth of the planet’s mass. The minimum is similar to Earth.

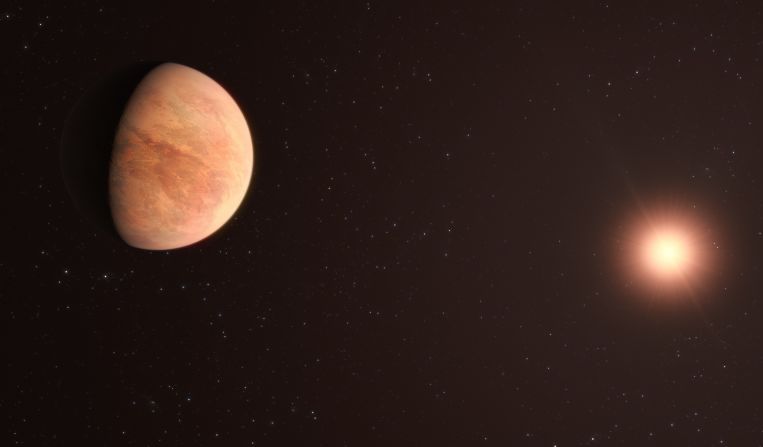

The researchers believe that K2-18b is potentially habitable and able to support liquid water based on their findings, especially when combined with previous research about its water vapor content and temperature.

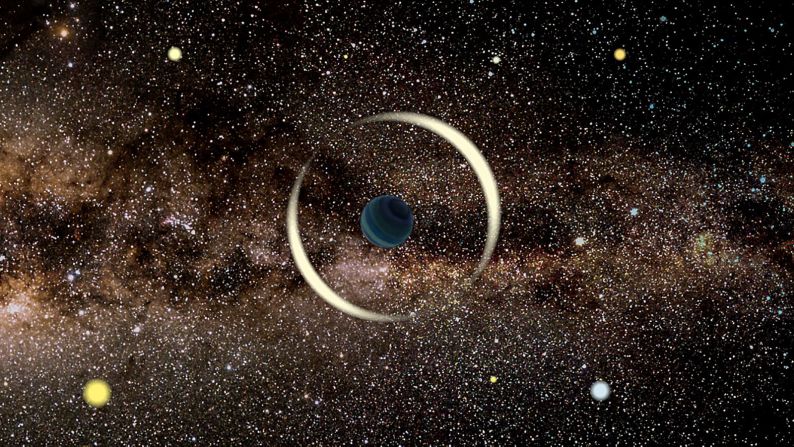

Based on their models, the researchers believe this opens up the search for life outside of Earth to planets much larger than our own. And when NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launches next year, it could peer into this exoplanet’s atmosphere to learn more about its composition.

So far, small, Earth-size rocky planets have been targets in the search for potentially habitable exoplanets. But the ones dissimilar from our own may create another opportunity.