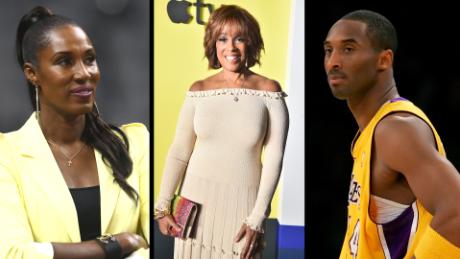

(CNN)From the time he began shooting make-believe game winners with his dad's rolled-up tube socks, Kobe Bean Bryant always wanted to ball. But his years on the court don't begin to sum up a life that spilled off the hardwood and into fans' hearts.

The love was on full display Monday as fans and celebrities -- an A-list cast by even Hollywood standards -- packed the Staples Center to remember one of their own.

Astronomers say when the biggest stars die they become supernovae, shining brighter than the Milky Way and capable of spurring the formation of other stars.

Bryant was one such supernova. "A 6-6 guard from Lower Merion High School" in Pennsylvania, he joined the NBA in 1996 as a child. Over 20 seasons, he won five championship rings and forged an extraterrestrial reputation as a suffocating defender and one of the greatest scorers to ever bounce a Spalding.

Though his playing career ended in 2016, his drive and passion never waned. In bidding the game he loved farewell, he wrote a short film that won an Oscar. He poured his retirement into his family, his production company and his Mamba Sports Academy, where the formation of young stars is part of its mission.

The trifecta forms the foundation of Bryant's legacy, which since his death has become its own universe. Meanwhile, the tears and remembrances -- from fans, fellow players and those he lifted up -- haven't stopped.

His death stunned the world

Bryant was stolen from this Earth on January 26 when a helicopter carrying him, daughter Gianna and seven others to a competition at his Newbury Park academy crashed into the Santa Monica Mountains in Calabasas.

He'd planned to coach 13-year-old Gianna's team that day as part of his post-career goal of empowering the next generation and instilling in them his storied Mamba mentality.

When his vision was cut short that Sunday, the world stopped -- first in incredulity, then in sorrow. "This can't be!" morphed into "How, how, how?"

Tears fell from Lower Merion to the streets of L.A. and beyond. Tributes arrived from Argentina, the Philippines, the Australian Open and all over Europe, Africa and Asia. In China, his death topped trends on Weibo, the social media platform, briefly outpacing posts about coronavirus.

Perhaps not since Prince has the world so collectively and deeply mourned one of its beloved.

As with Prince, the legacy Bryant leaves behind is complicated. It's easy to recall the times he shined, but there were also dark moments that left his faithful struggling to reconcile a dichotomy that's inherent in all humans but especially visible in those who spend their lives on stage.

He was a baller in everything he did

Every generation has its GOAT. They tend to go by one name. Before Kobe, the NBA had Kareem and Jordan. Now, LeBron.

Of the 11 numbers the Lakers have retired -- among them, Kareem's, Worthy's, Wilt's, Magic's -- two belong to Bryant: the No. 8 he wore in his early days with the Lake Show and the No. 24 he resurrected from high school for the latter half of his pro career.

In everything he did, Bryant was a baller, literally and figuratively -- from taking Brandy to prom to challenging His Airness Michael Jordan during his first All-Star Game to putting 60 on the Utah Jazz in his farewell performance.

When he jumped from high school to the NBA in 1996, the path was uncharted for a guard. Few had achieved the feat without struggles -- Moses Malone, Darryl Dawkins, Shawn Kemp and Kevin Garnett -- and they were all big men, or bigger than Bryant.

What he lacked in size, which was not much, he made up for in preparation. He trained relentlessly, whether shooting thousands of jumpers to perfect his stroke or running sand dunes to improve his conditioning.

Anyone who witnessed him in person saw the product of his devotion, how he glided into position, feinted like an apparition and lobbed impossible jumpers that had no chance of dropping -- only they did. There were times he couldn't be covered with a fishing net. If you aren't part of Laker Nation, chances are he broke your heart more than once.

In letting the game he loved go after 20 seasons, Bryant continued to exude an air of excellence, snaring an Oscar for his animated ode to the sport, "Dear Basketball."

"I did everything for you -- because that's what you do when someone makes you feel as alive as you've made me feel," he said in the short film. "My heart can take the pounding, my mind can handle the grind, but my body knows it's time to say goodbye, and that's OK. I'm ready to let you go."

To some he was polarizing

When a revered man dies, the lines between hagiography and history are blurred, but anyone who's lived a life worth living deserves to see his legacy fully explored.

Humans struggle when their favorite people leave complex legacies. Look no further than Michael Jackson. They'll struggle again when Woody Allen, Roman Polanski and Mike Tyson meet their makers.

Bryant's been remembered in glowing terms these past four weeks, but his shortcomings, too, are part of his lore, no matter how painful they are to remember.

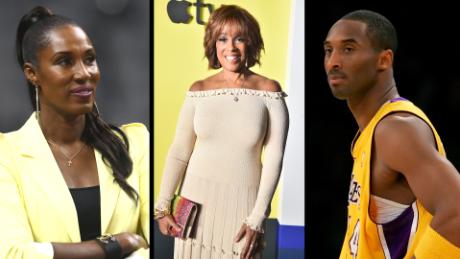

In what now looks like prescience, ESPN's Ramona Shelburne, who covered much of Bryant's career, said during a 2017 interview, "I don't think Kobe was beloved in his time. He may be somebody who is remembered more fondly by history than he was in his time. The guy was very polarizing when he played."

As great as Bryant was, he snared only one MVP. He was labeled cocky, a ball hog, a bad teammate. He was accused of quitting in the 2006 playoffs. Phil Jackson, one of basketball's most innovative minds, called him "uncoachable." He was fined for hurling a gay slur at a referee.

In the middle of his career, he threatened to play for the loathed crosstown rival Clippers, or on Pluto, one being no worse than the other to Lakers fans.

And, of course, there were the 2003 sexual assault allegations in Colorado, which ended with him being cleared of criminal charges. He and his accuser later settled a civil suit out of court.

Any one of these things, let alone two or three, could have killed most mortals' careers -- forget their legacies. Yet in Bryant's oh-so-Kobe way, he dealt with them directly and effectively.

But he never lacked confidence

To bring up his perseverance in the face of shortcomings is not to castigate him in death but to cast light on important parts of his legacy.

Yes, he silenced haters with Ws and trophies, but for someone with his drive and talent, that wasn't the difficult part. Even as a teenage newbie to The Association, he saw himself as ready for any challenge.

Take his first All-Star Game in 1998, which he started despite not starting for the Lakers. Undeterred, he irked veteran (and future teammate) Karl Malone, telling him he didn't need his screens. It was seen as brash for a young buck, but everyone in Madison Square Garden knew what Bryant was up to: He wanted a piece of Jordan.

"Kobe has challenged Michael," color commentator Isiah Thomas pointed out to the home audience. "Michael comes out and says, 'Not tonight, young fella. I'm bringing all my tricks.' Kobe comes back, he says, 'Michael, I'm stealing it. I'm taking it. I want the torch.'"

During a halftime interview, Bryant chalked it up to his desire to grow, telling reporter Jim Gray, "Michael's a great player, one of the best players of all time. What better way to learn the game than going right at him?"

Over the years, many would attribute Bryant's cockiness to his confidence, his ruthlessness, his I'm-always-the-best-option philosophy. Handouts were never his thing. He'd take what he wanted.

In one of his final interviews last year, he said he'd never join a so-called NBA superteam, even if it meant a sixth ring to tie Jordan.

"I like my rings the hard way," he said. "I like fighting through them and earning them that way."

He built a new image in retirement

The same determination would help him restore his image off the court. After issuing an apology for the gay slur, he became an advocate for the LGBT community, filming a local PSA and publicly chiding fans who would use "gay" as an insult.

He was one of the first players to support Jason Collins coming out, prompting the NBA's first openly gay player to lament after Bryant's death, "He was there for me & supported me when I needed it. He evolved so much as a human being, & his words meant the world to me."

Bryant also apologized to his accuser in the sexual abuse case, making a risky concession that he realized she did not consider their encounter consensual. That wasn't good enough for many people. It never will be. For his legions of fans, his words were sincere.

His missteps were a product of his human fallibility, he'd say, telling Shelburne in his final year of hoops, "We all say s*** that we shouldn't say. We all do things we shouldn't do. We all are angels. We are all devils."

In his later years, Bryant loaded his angel resume. He became the consummate "girl dad," doting on his four daughters. He turned up the volume on his advocacy for women's sports. His Mamba Academy served all children, but with a special focus on girls and the less fortunate. He lent his wealth and star power to myriad causes, from cancer and natural disaster relief to after-school programs and opportunities for inner-city kids.

That's not to mention the more than 200 dreams he fulfilled for the Make-a-Wish Foundation, including taking a rare beating in a game of H-O-R-S-E.

He held the notion, rare among pro athletes, that his vocation was just a game and his true reach would be realized later, away from the cameras and spectators.

In October, during his last interview with Los Angeles Times columnist Arash Markazi, he said of his Mamba Academy's role in how he's remembered, "If we do it the right way, (we'll) be known for more of what we do after than what we did during."

In the growing Legend of the Black Mamba, what Bryant did on the court will never be forgotten. What he accomplished after basketball, in the last chapter of his life, will be long remembered as well.