Editor’s Note: Paul French is the author of “Midnight in Peking” and “City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir,” both currently being adapted for TV.

Before the novel coronavirus outbreak hit Wuhan in December, the exact whereabouts – and even existence – of the central Chinese city had slipped from the general public’s awareness in the West.

But it wasn’t always that way.

Two generations ago, this city of 11 million people, on the junction of the Yangtze and Han Rivers, 600 miles upstream, in central China, was known through the West as a major industrial city.

It was somewhere many European powers had a consulate, a place where major Western and Japanese trading firms, and international textile and engineering companies, had factories and sales offices.

It was a regular overseas posting for customs officers, steamboat captains, traders and consuls. Wuhan was also a cradle of China’s revolution in 1911. A quarter of a century later, it stood defiantly as the beleaguered wartime capital of nationalist China.

From the middle of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century, Wuhan was a city that regularly appeared in the international press and, as a trading hub for teas and silks among other commodities, it directly impacted the lives of people in the West – it made the tea in their teapots, the powdered egg in their birthday cakes, the silk for their pajamas.

After the chaos and destruction of the Second World War, the Communist Revolution brought the Bamboo Curtain firmly down. International trade stopped, the foreign business community left, and the Western world largely forgot about Wuhan.

The Chicago of China

In 1900, American magazine Collier’s published an article about the Yangtze “boom town” of Wuhan, calling it “the Chicago of China.” It was one of the first times – if not the first – the Chinese city had been given this moniker, and it stuck.

In 1927, the veteran United Press Shanghai correspondent Randall Gould used the moniker in a dispatch about political turmoil in Hubei province. After this, the term appears hundreds of times in just about every paper around world.

Minnesota-born Gould was fairly fresh off the boat in Shanghai when he journeyed up the Yangtze to Wuhan for the first time. Gould was in town because a revolution was going on – the second in Wuhan in 15 years. The Nationalist government, led by Chiang Kai-shek, had split over the bloody suppression tactics used in its brutal war against the nascent Communist Party.

Left-wing sympathizers established the breakaway Wuhan Nationalist Government, while Chiang formed his own majority government in Nanjing. The alternative government in Wuhan only lasted six months, but it revealed the long-running divisions within the Chinese Nationalist Party. To foreign correspondents like Gould, it looked like the young Chinese republic was about to wrench itself apart.

Their editors in London, New York, Paris and Tokyo agreed. Wuhan was front page news.

That editorial decision was partly influenced by the long list of companies with substantial stakes in Wuhan in 1927 – the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank (HSBC), John Swire & Sons, British-American Tobacco, Standard Oil of New York, Texaco, Standard Chartered Bank.

Wuhan was China’s major industrial powerhouse, producing iron and steel, silk and cotton, tea packing and food canning.

It was the Chicago of China.

The West’s introduction to Wuhan

The West came to know Wuhan in 1858 as part of the unequal Treaty of Tianjin, extracted from the weakened Qing Dynasty during the Second Opium War.

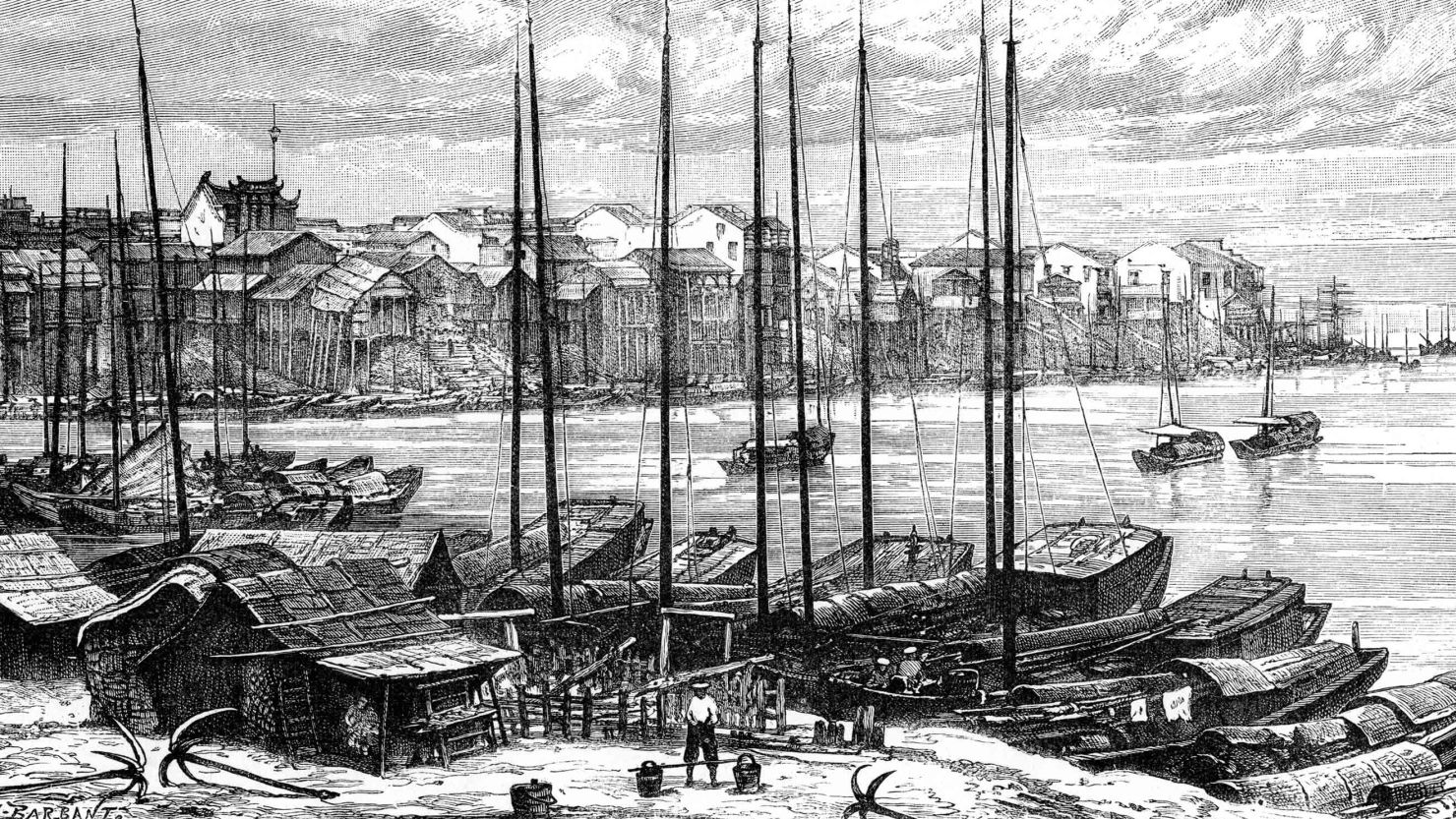

The treaty allowed foreign ships to sail up the Yangtze River, and the British had surveyed the waterway as far as Hubei province. They particularly examined the riverside conglomeration of Wuchang, Hankou and Hanyang, collectively known as the “Three Towns of Wuhan.” Liking what they saw, they demanded the city be opened to foreign trade.

Robert Bickers, a professor at Bristol University, who studies the foreign presence in pre-1949 China, explains the British thinking: “After the First Opium War the British annexed Hong Kong as a colony and opened Shanghai, on the coast at the head of the Yangtze in eastern China, as a treaty port. Sixteen years later they understood the importance of inland China better and so zeroed in on Wuhan, as well as Tianjin.”

Wuhan became essential to the coastal port cities, feeding them commodities (tea, meat, tobacco etc) and produced outputs (iron, steel, silk etc). Wuhan was China’s largest inland entrepôt.

Wuhan was already a massive in city in 1850 – approximately 1 million people lived in the three towns half the size of the world’s largest city at the time, London.

From the 1860s, foreigners flooded in, though the city always had a Chinese majority population.

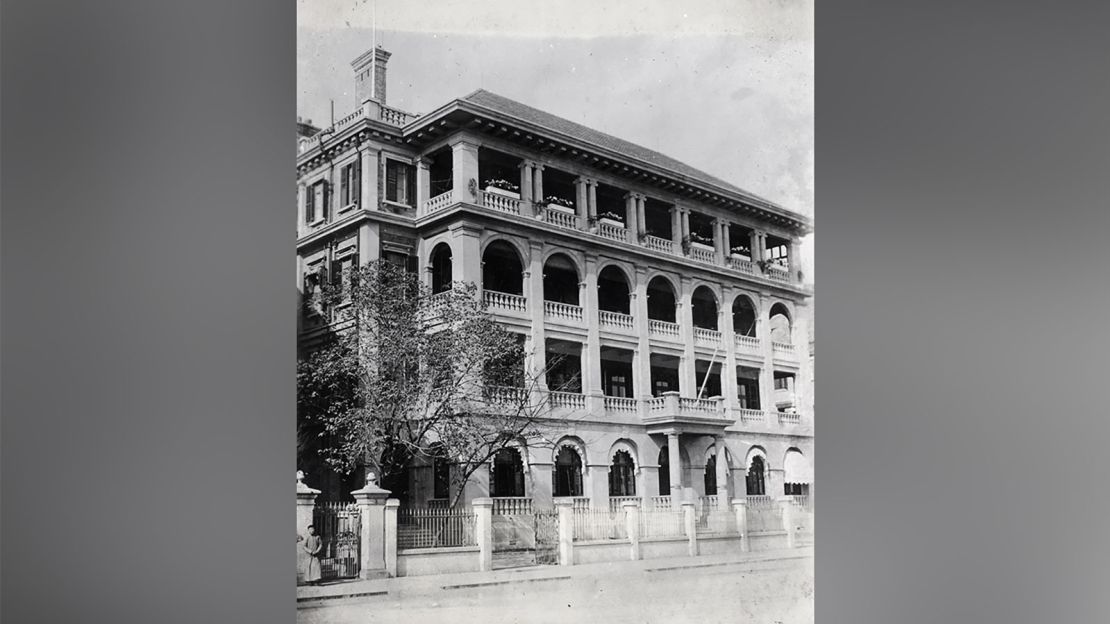

The new arrivals clustered in Hankou creating a tree-lined, two-mile long Bund, which largely remains today, building their warehouses, docks and offices as well as a race track, clubs and public gardens all adjacent to the Hankou waterfront.

The British Concession was adjacent to concessions run by the Germans, the French, the Japanese, a rather disputed Belgian concession, and the Russians, who had been active in Wuhan trading tea from Siberia since the 12th century. All these nations, including the Americans, had consulates.

While Wuhan became a cosmopolitan place, it was always essentially a business town – it never developed the nightlife or the movie industry, publishing houses, and art galleries that clustered in Shanghai’s more Bohemian quarters; it wasn’t quite the scholarly center that was Beijing. The foreigners were present, and their soldiers guarded the consulates, but the city retained a more dominant Chinese feel.

Center of revolt

In 1911, the republican revolution that overthrew China’s last imperial dynasty was, albeit accidentally, sparked in Wuhan.

The initial catalyst for the revolt was the accidental explosion of a bomb that occurred when a careless anti-Qing/pro-republican revolutionary dropped a lit cigarette in the workshop of some rebel conspirators in Hankou’s Russian Concession.

The ensuing explosion alarmed a nervous German butcher who called the police, who in turn uncovered a revolutionary plot. Seals, plans and documents were seized implicating members of the city’s Wuchang Garrison of Chinese soldiers as revolutionaries preparing to mutiny. As police had seized their membership list, the rebels were faced with a choice between arrest, torture and probable beheading or putting up a fight. They decided to act immediately to preserve themselves.

The anti-Qing rebellion took hold and eventually ended the 267-year-old Qing Dynasty.

In general, foreign business welcomed the new republic and saw it as a harbinger of greater support for modern industries.

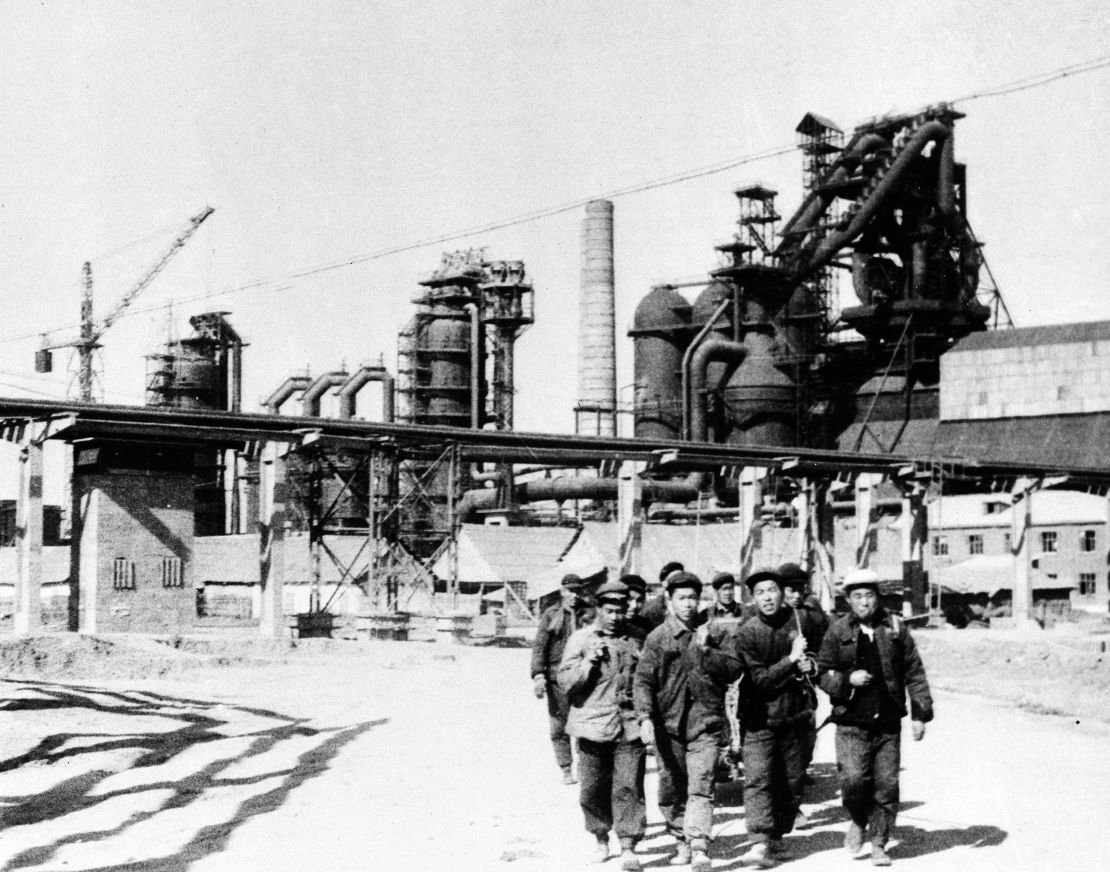

Indeed, Wuhan was awash with new industrial ideas and technologies. The city was home to several major Chinese heavy industries – the Hubei Arsenal and Powder works, Hanyang Iron and Steel, a railway line to Beijing, regular steamer services to Shanghai, a mass of silk filatures, cotton mills and canneries. The city’s furnaces made a high percentage of the world’s horseshoes – a product as important in the late 19th century as tires today.

Its stock yards boiled down pig carcasses by the hundreds of thousands to extract millions of pig bristles for export to Europe and America – the major, and essential, component in the booming toothbrush market. Wuhan was also a center of egg production – fresh eggs, preserved, powdered, liquid – and exported them to food manufacturers, restaurants and bakeries around the world.

As Wuhan became more industrially significant globally, its role as an export powerhouse gave the city national power.

Robert Bickers notes that the city “unobtrusively entered consumers’ lives in Europe and America.” But some foreign buyers didn’t believe that China could produce iron, steel, and food to Western standards.

Yet China was manufacturing steel and iron for its new railways, bridges and urban construction while also ramping up its armaments industry to create a newly-organized modern army under Chiang Kai-shek’s command. Ways around these foreign prejudices had to be found. Comparatively low pricing was one way to convince cost-conscious buyers, others were a little more creative.

Carl Crow, an American advertising executive who lived in China between 1911 and 1937, visited Wuhan regularly and saw how the Chinese manufacturers got around this problem.

Crow recalled in his classic 1937 guide to doing business in China, “Four Hundred Million Customers,” that the iron and steel mills often stamped their products “Made in Hamburg,” while sewing needles read “Made in the USA.” In the US, meanwhile, foreign eggs were considered low-quality so they shipped them in boxes marked “England,” where produce was considered good. Nobody noticed a thing.

A target

Wuhan officials insisted that international trade deals be done in Wuhan and not, as was often the case in other treaty ports, negotiated in the palatial offices and swish private clubs of Shanghai. Therefore a larger portion of the money from this business stayed in the city and didn’t flow out to Shanghai or Guangzhou.

It reinvested at least some of that money. The Europeans and Americans may have landscaped their concessions in Hankou, but Chinese Wuhan was also considered beautiful. The sprawling garden campus of Wuhan University covers the city’s Luojia Hil. This institution is where Virginia Woolf’s nephew, Julian Bell, taught English in the mid-1930s. He thought it idyllic.

But by the late 1930s, Wuhan’s strengths made it a target. The Japanese had long invested in the city, operating cotton mills, cotton-seed oil factories, and bean processing plants, and keenly regarded it.

Japan invaded eastern China in the summer of 1937. They bombed Shanghai and horrifically raped the Nationalist capital of Nanjing. The government was forced to retreat further up the Yangtze to Wuhan. Chiang Kai-shek’s temporary capital there once again featured on the front pages of the world’s newspapers.

Ultimately doomed, Wuhan fell to the Japanese in October 1938. Much of the city’s industry was physically dismantled and transported further up the Yangtze to the final Nationalist capital of Chongqing, where it was to form the backbone of China’s wartime heavy industry.

After the war, even with severely reduced exports, Wuhan resumed its position as China’s largest industrial center and inland port along the Yangtze.

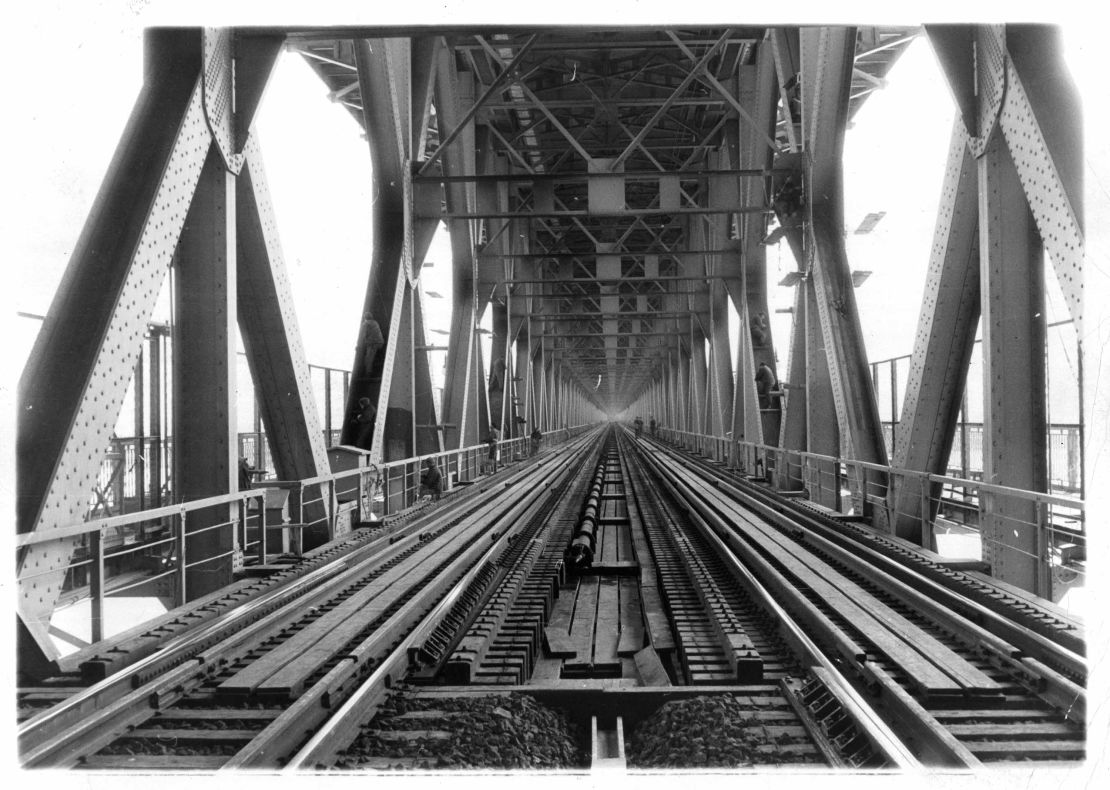

In the 1950s, the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge connected three major rail lines making Wuhan once again the country’s major central rail terminus.

But by then foreign business was gone; the old Bund and concessions had been shuttered or repurposed.

Wuhan slipped from our collective memories. But life went on, industry went on and, in the 1980s, foreign business began to return.

Wuhan emerged as a center of auto production – Honda, Citroen and GM are among major investors in the city, while pharmaceuticals and new environmental technologies flourished in the city.

But Wuhan rarely made it to the front pages again, until now.