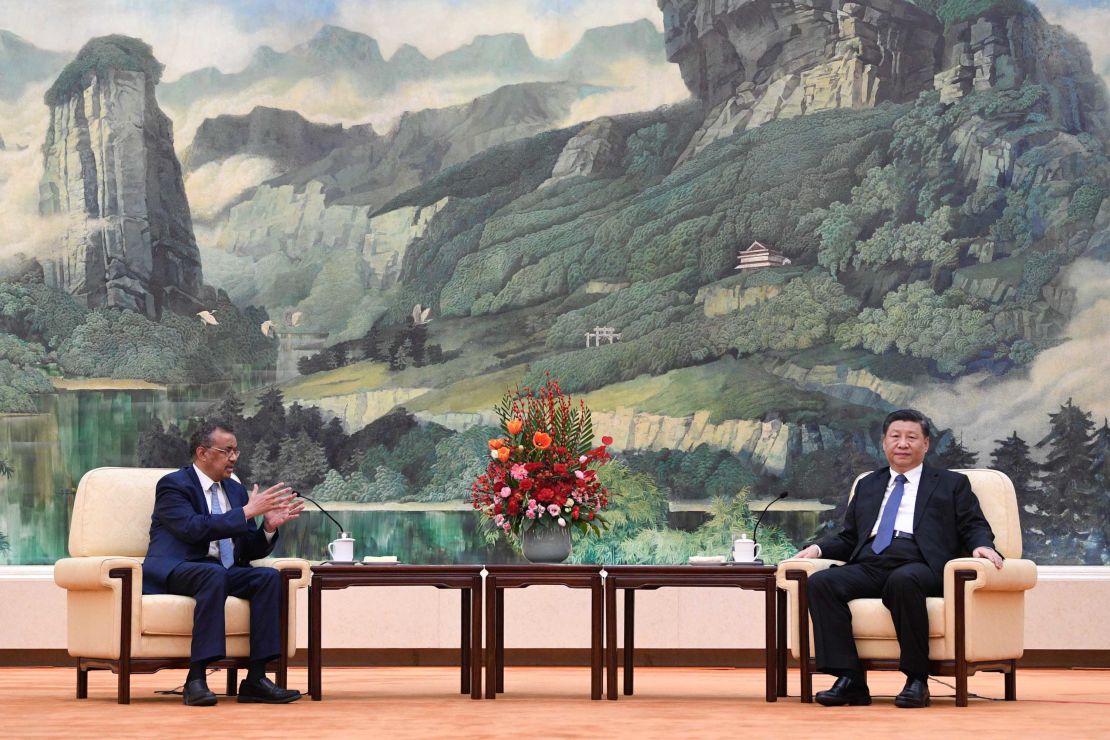

Sitting alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, World Health Organization director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was effusive in his praise of the country’s response to the coronavirus crisis.

“We appreciate the seriousness with which China is taking this outbreak, especially the commitment from top leadership, and the transparency they have demonstrated,” Tedros said, in comments that would berepeatedly quoted inChina’s state media for weeks.

This was in late January, after Xi had taken control of the situation due to local officials’ apparent failure to contain the outbreak to Hubei province.

As the two men met in the Chinese capital, the number of cases was rising, and revelations were emerging that officials in Hubei province and Wuhan – the city where the virus was first detected – had sought to downplay and control news about the virus, even threatening medical whistleblowers with arrest.

Days later, the WHO declared a global public health emergency, and once again Tedros praised Beijing’s response.

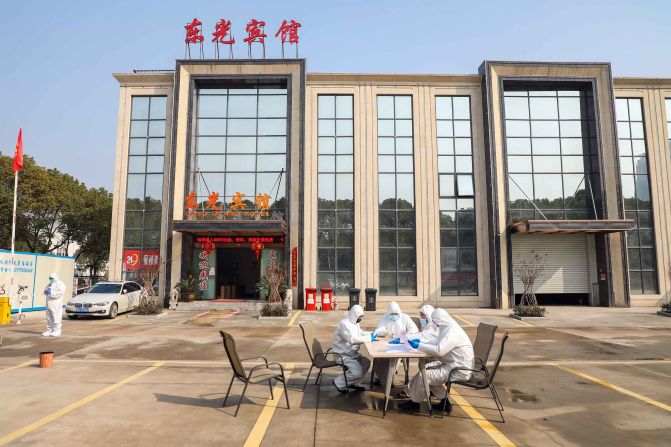

While China did act quickly following Xi’s intervention, placing several major cities on lockdown and pouring resources into the battle against the virus, it has maintained tight control over information about the virus and efforts to control its spread have veered on the side of draconian.

The WHO’s praise of China’s response have led critics to question the relationship between the two entities. The UN agency relied on funding and the cooperation of members to function, giving wealthy member states like China considerable influence.Perhaps one of the most overt examples of China’s sway over the WHO is its success in blocking Taiwan’s access to the body, a position that could have very real consequences for the Taiwanese people if the virus takes hold there.

The WHO’s position regarding China has also renewed a longstanding debate about whether the WHO, founded 72 years ago, is sufficiently independent to allow it to fulfill its purpose.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not respond to questions regarding Beijing’s relationship with the WHO.A spokesman for the WHO directed CNN to comments made by Tedros this week, when he again praised China for “making us safer.”

“I know there is a lot of pressure on WHO when we appreciate what China is doing but because of pressure we should not fail to tell the truth,” the WHO director said. “We don’t say anything to appease anyone. It’s because it’s the truth.”

Tedros added that “we are giving qualified recognition and actually my call is, please, let’s recognize as a world, as a globe what China is doing and help them and show solidarity.”

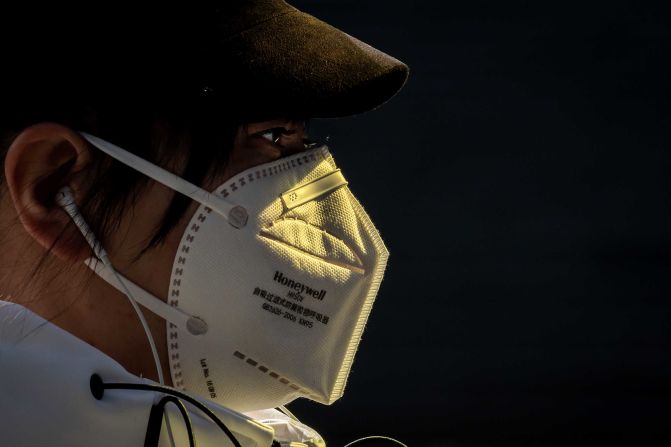

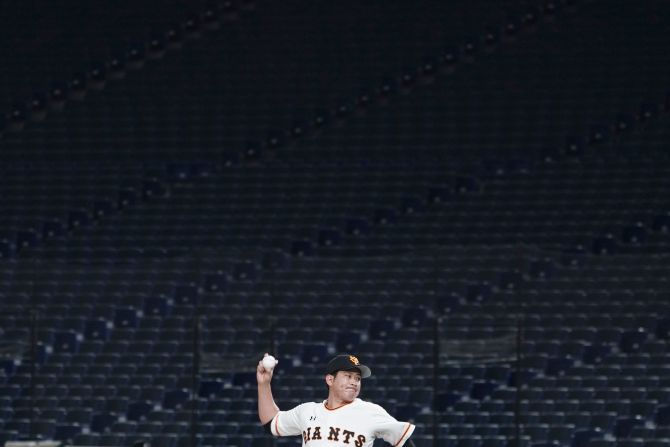

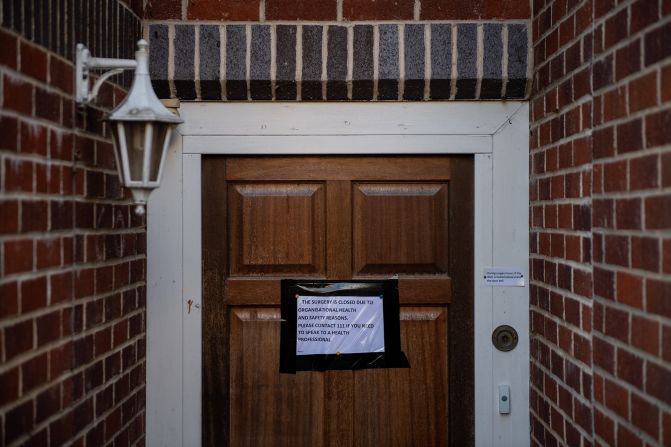

In pictures: The novel coronavirus outbreak

Mixing health and politics

The WHO was founded in 1948 under the auspices of the still infant United Nations (UN), with a mandate to coordinate international health policy, particularly on infectious disease. Since then it has had many successes, chief among them the eradication of smallpox and a 99% reduction in polio cases, as well as work against chronic disease and tackling tobacco usage.

But in its seven-decade history, the WHO has rarely been without its critics. They argue that it is overly bureaucratic, bizarrely structured, too dependent on a handful of major donors, and often hamstrung by political concerns. Following his election in 2017, Ethiopian politicianTedros became the latest WHO director general to promise large-scale reforms.

The first African to hold his position, Tedros took over following the WHO’s self-acknowledged poor response to the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa. The WHO took five months to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) over Ebola, a delay that “undoubtedly contributed to the unprecedented scale of the outbreak,” according to one academic assessment.

The failure was blamed in part on the WHO’s cumbersome and complex bureaucracy – it is made up of six regional offices which are only loosely controlled by headquarters in Geneva. Other factors blamed for the Ebola failure include an overstretched and underfunded surveillance team, and political pressure from West African governments unwilling to take the economic hit caused by a PHEIC declaration.

In a statement to CNN, a WHO spokesperson said that “as a result of the lessons learned from West Africa, WHO established the new Health Emergencies Programme,” which was “a profound change, adding operational capabilities to WHO’s traditional technical and normative roles.”

“The program is designed to bring speed and predictability to WHO’s emergency work,” the spokesperson said. “It brings all of WHO’s work in emergencies together with a common structure across headquarters and all regional offices in order to optimize coordination, operations and information flow.”

But while Ebola may have highlighted some issues, experts had been sounding the alarm for years. In a 2014 report, former WHO consultant Charles Clift wrote that most observers – including many former insiders – agreed that the organization “is too politicized, too bureaucratic, too dominated by medical staff seeking medical solutions to what are often social and economic problems, too timid in approaching controversial issues, too overstretched and too slow to adapt to change.”

“The WHO is both a technical agency and a policy-making body,” Clift wrote. “The excessive intrusion of political considerations in its technical work can damage its authority and credibility as a standard-bearer for health.”

The WHO relies in part on data provided by member states, filtered through regional organizations – a structure that was blamed for the delays in declaring Ebola an emergency.

With a government like China’s, with a historical aversion to transparency and sensitivity to international criticism, that can be a problem.

Taiwan in the dark

It is on the issue of Taiwan that Beijing’s political sway at the WHO is most clear.

In an impassioned speech last year before the World Health Assembly (WHA), the organization’s annual meeting in Geneva, Luke Browne, the youthful health minister of the Caribbean nation of St. Vincent, demanded that Taiwan be allowed a seat at the table.

“There is simply no principled basis why Taiwan should not be here … the only reason that it is not here now is because the government in Beijing does not like the current government in Taiwan,” Browne said.

Despite Browne’s speech, and the intervention by several other member states, from Belize and Haiti in the Caribbean to the African kingdom of Eswatini and the tiny Pacific nation of Nauru, the proposal to include Taiwan was swiftly struck off the agenda, as it has been every year since 2016.

Taiwan is a self-governing democratic island of 23.7 million people off the coast of China. It has never been ruled by the government of the People’s Republic, but is claimed by the authorities in Beijing as part of their territory. Beijing blocks Taiwan from participating in many international organizations unless it does so in a way that conforms to the “one China” principle, such as calling itself “Chinese Taipei” in the Olympics.

Beijing’s exclusion of the island from international organizations does not usually have global ramifications. Health is one area, however, where an effective international response requires that all governments be equally connected and informed.

“Taiwan’s exclusion from the WHO leaves its population vulnerable during this crisis – a lack of direct and timely channels to the WHO have already resulted in inaccurate reporting of cases in Taiwan,” said Natasha Kassam, an expert on China, Taiwan and diplomacy at Australia’s Lowy Institute. “Taiwanese authorities have complained about the lack of access to WHO data and assistance.”

Similar concerns were raised during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, when Taiwanese scientists complained they were stonewalled by WHO officials, who told them to ask authorities in China for data about the disease.

The issue has global ramifications: Kassam pointed out that around 50 million foreign travelers pass through Taiwan’s largest airport every year, “with an expectation that Taiwan would be receiving WHO advice on any public health issue.”

“Taiwan’s healthcare system has been consistently ranked one of the best in the world – and at a time like this, every country should put politics aside to focus on containing the virus,” Kassam said.

As coronavirus cases were reported in Taiwan – which has major business and cultural links with China no matter the discord politically – the WHO couldn’t even settle on what to call the island. Speaking to reporters last month, a spokesman used the bizarre construction of “China, Taiwan;” while a February 4 report flipped it and listed “Taiwan, China,” but got the number of cases wrong, relying on data from Beijing not Taipei. Subsequent reports have since dropped the term Taiwan altogether, instead including “Taipei and environs” in a list of affected cities in China.

When he addressed the WHA last year, Browne predicted just this type of confusion, saying “we all know that the PRC does not exercise control and authority over Taiwan and cannot be reasonably expected to represent it here.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for the WHO said that “we are collaborating closely with Taiwanese authorities through the International Health Regulations (IHR) mechanism in response to the COVID-19 outbreak.”

“WHO has received vital information from Taiwanese authorities and will be reporting back through established channels,” the spokesperson said. “WHO works with Taiwanese health officials, following established procedures, to facilitate fast and effective response, including through the IHR.”

The spokesperson added that with regard to the current outbreak, ‘we have Taiwanese experts involved in all of our consultations – the clinical networks, laboratory networks, and others – so they’re fully engaged and fully aware of all of the developments in the expert networks.”

Trapped in the middle

Just as Beijing’s sway at the United Nations means that Taiwan is likely never to regain its seat there, the WHO is unlikely to reverse course on this issue until Beijing does. While Taiwan’s allies have spoken out in favor of it since the coronavirus outbreak began, China has far more diplomatic clout that it can bring to bear.

And this is the fundamental problem with the WHO: it cannot treat member states equally because they are not equal. During the Cold War, it was the United States that was seen as having too much influence, leading the Soviet Union and its allies to walk out from 1949 to 1956. The US retains major sway due to its position as one of the largest individual funders of the WHO, as do other major economies such as Japan and the United Kingdom, and private donors like the Gates Foundation. While it has not historically been a major funder, the WHO has praised China’s “growing contribution” to global health initiatives.

Beyond financial issues, the WHO is also directly controlled by its member states, who nominate and elect the organization’s director general and set its agenda. This means the WHO cannot afford, politically or financially, to antagonize countries like the US or China that wield outsized influence over other nations.

“If Tedros wants WHO to stay informed about what’s happening in China and influence how the country handles the epidemic, he cannot afford to antagonize the notoriously touchy Chinese government – even though it is clear the country has been less than fully transparent about the outbreak’s early stages, and perhaps still is,” Kai Kupferschmidt wrote in the journal Science this week.

Indeed, had Tedros done so, there would likely have been a raft of articles criticizing the WHO for needlessly offending China at a time of crisis and hamstringing its own ability to operate.

Thomas Abraham, an associate professor at Hong Kong University Journalism and Media Studies Center and former WHO consultant, sums it up well: “The WHO, and China too, is in a damned if you do, damned if you don’t situation.”

This article has been updated to reflect additional comment from the WHO.