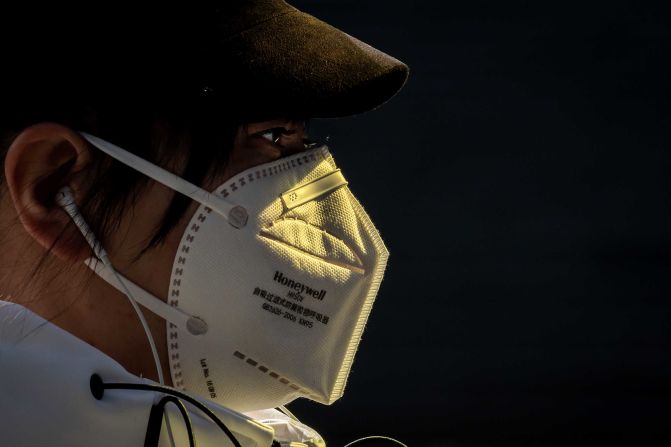

On a French newspaper’s front page last weekend, big block letters announced “Yellow Alert” next to an image of a Chinese woman wearing a face mask. Another headline in the same paper read “New Yellow Peril?” above an article about the ongoing Wuhan coronavirus outbreak.

The headlines drew immediate outrage. Readers accused the paper of using ignorant and offensive language.

“Yellow Peril” was an old racist ideology that targeted East Asians in Western countries. The phrase embodies the worst of anti-Asian fears and stereotypes, which have plagued immigrant communities since the first waves of Chinese immigration to the United States began in the 19th century.

In the US, government propaganda and pop culture at the time spread wildly racist and inaccurate images of Chinese people as unclean, uncivilized, immoral, and a threat to society.

To invoke the term now, in a story about death and illness in Asia, seems thoughtless at best and blatantly racist at worst.

The newspaper apologized quickly and said they had no intention of perpetuating “racist stereotypes of Asians.” But the damage is not so easily undone, and the paper is not the sole culprit – merely the latest in a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment as the coronavirus spreads worldwide.

The escalating global health crisis has claimed more than 200 lives – all in China – and infected close to 10,000 people worldwide. As they seek to contain the virus, authorities in multiple countries are balancing the need for warnings against the risk of creating global panic.

However, there are signs that’s already happening, with face masks selling out in stores and people locking themselves at home. Some people in central China – the epicenter of the outbreak – are desperately taking any flight out, regardless of destination, as governments worldwide suspend flights from China and impose restrictions on travelers from the mainland.

But the panic has also taken another, more familiar form, with the re-emergence of old racist tropes that portray Asians, their food, and their customs as unsafe and unwelcome.

As panic spreads, so does racism

As news of the virus has spread, many people of Asian descent living abroad say they have been treated like walking pathogens.

Writing for the UK’s Guardian newspaper, one British-Chinese journalist in London said a man quickly moved seats when he sat down on a bus.

A Malaysian-Chinese social worker experienced the same thing on a London bus this week. “A couple of people at an East London school I work in have asked me why Chinese people eat weird food when they know it causes viruses,” she told CNN.

In Canada, there have been reports of Chinese children being bullied or singled out at school. In New Zealand – where there are no confirmed coronavirus cases – a Singaporean woman says she was confronted and faced racist harassment in a mall.

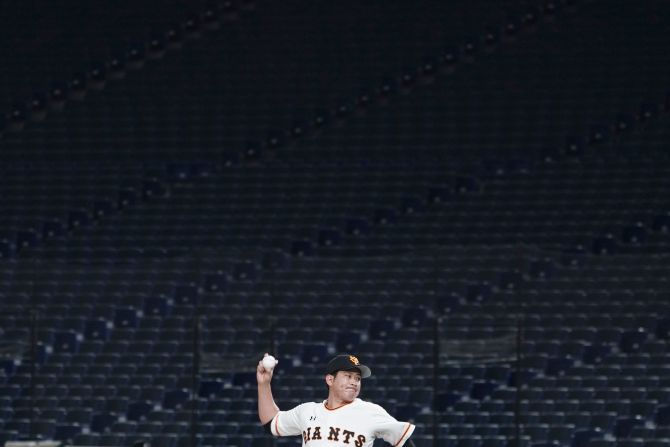

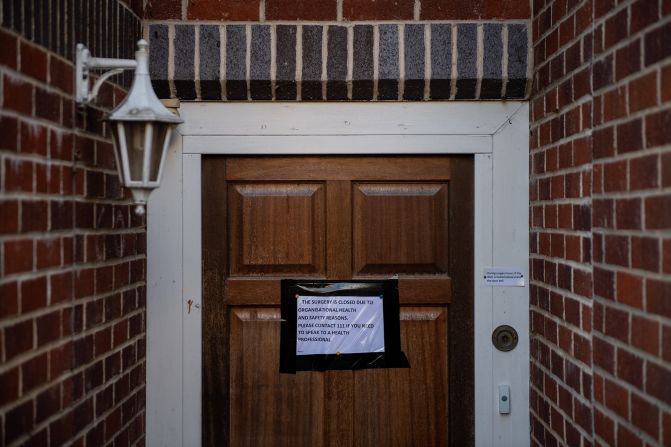

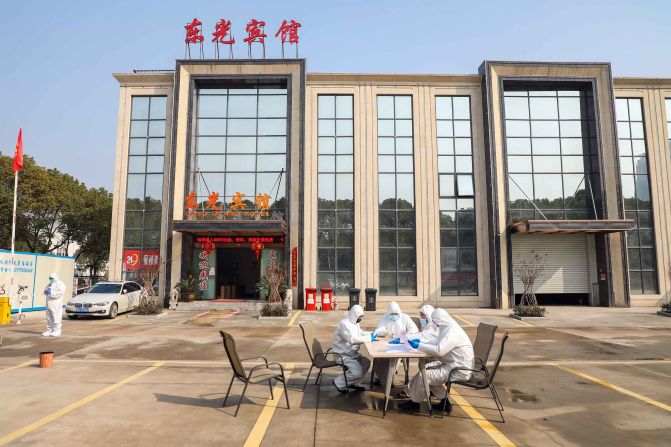

In pictures: The novel coronavirus outbreak

These instances echo a long history of racism in the West. During the Yellow Peril era, anti-Chinese fears led to lynchings of Chinese immigrants, racial violence, systemic discrimination – even an outright ban on Chinese immigrants for 61 years in the US under the country’s Exclusion Act.

That’s why the term “Yellow Peril,” which contains centuries of trauma, is so charged – and why the use of it in a contemporary headline was so stunning.

However, this time around anti-Chinese racism is spreading beyond the West. In Vietnam, signs have been seen outside restaurants declaring “No Chinese.” The tourist who took the photo told CNN the sign appeared in the past week. Similar signs were also posted outside a Japanese shop, turning away Chinese customers.

And people online from various different places are making racially driven jokes; when TV host James Corden posted a photo with Korean-pop band BTS, one person tweeted, “BREAKING: James Corden dies of the coronavirus.” The joke racked up nearly 25,000 likes on Twitter.

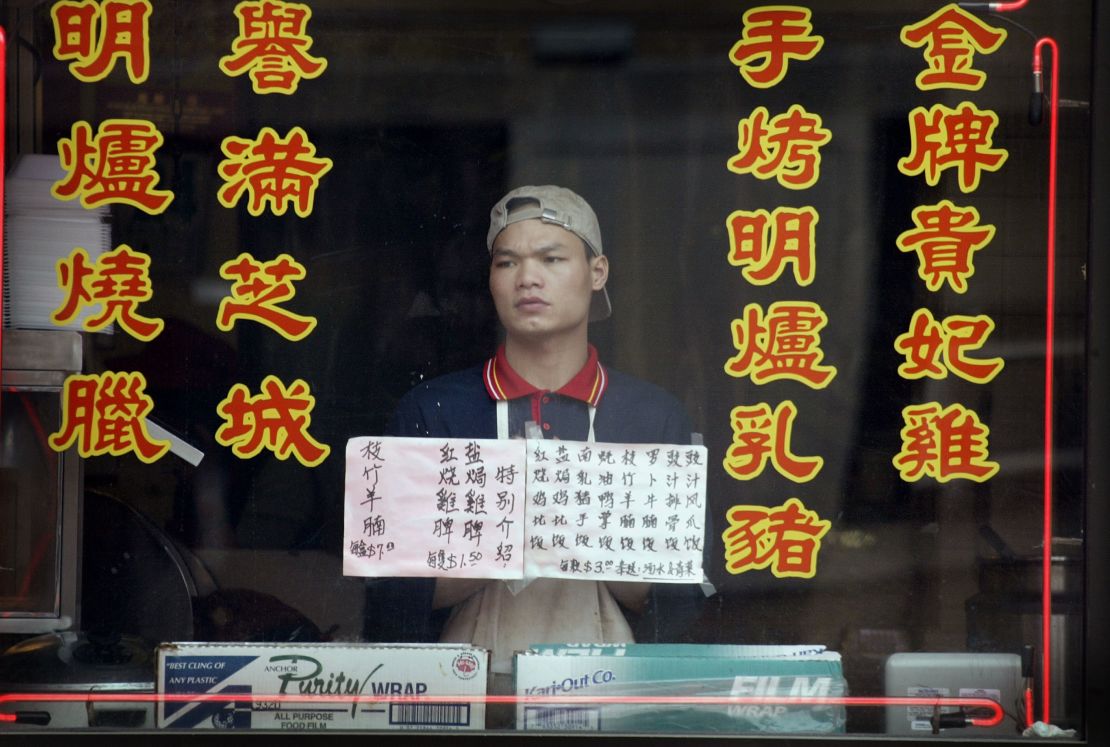

Targeting Chinese food

Perhaps the most widespread form of xenophobia comes in fearmongering, sensationalist stereotypes about Chinese food.

The novel coronavirus is believed to have started in a Wuhan seafood and wildlife market, and scientists have pointed to bats and snakes as possible virus carriers. And while the wildlife trade poses legitimate problems, the outbreak has prompted a racially tinged wave of disgust toward Chinese food, and anger from many who accuse Chinese people of recklessly causing a potential global pandemic.

“Because of some folks in China who eat weird (foods) like bats, rats, and snakes, the entire world is about to suffer a plague,” said one popular tweet.

This idea has been reinforced by recent media coverage of the coronavirus, some of which has featured misleading videos or photos. One widely shared video, of a Chinese travel blogger eating bat soup, was filmed three years ago in the Pacific island nation of Palau, and the dish has been sampled by Western TV hosts in the past.

The video and the blogger have no connection to Wuhan or the current outbreak – but the video has gone viral nonetheless, with many Western viewers expressing horror on social media. There was such an uproar that the blogger came forward to apologize last week.

What viral misinformation and breathless media coverage often miss is that only a small minority of people in China actually eat wild animals. Most people eat much of the same things you would see in other cuisines, like pork or chicken. Ultimately, what people like to eat is culturally relative – a lot of the Western disgust toward “weird” Chinese food is itself Eurocentric.

That’s not to say all criticism of Chinese food is invalid; the country does have a problem with badly-regulated trade of wild animals, which has led to previous outbreaks.

The deadly 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was traced to the civet cat, considered a delicacy in southern China. And though the government has introduced some measures limiting wildlife trade, it has been reluctant to take more aggressive action, and illegal trade continues.

It’s also difficult to end these practices because of the cultural significance and prevalence of traditional Chinese medicine. Many of these wild animals are thought to hold important medicinal properties – for instance, people drink snake soup for arthritis and snake bile for a sore throat.

There is undoubtedly a larger issue that needs to be addressed – how the government can balance tradition with safer regulations.

But the beliefs and customs that drive consumption of these foods are centuries old and interwoven in peoples’ lives – they are not so easy to undo, even less so when they are dismissed as primitive and unclean by foreign countries.

‘Standing with our Chinese community’

Right now, we are only seeing early signs of a xenophobic backlash against the East Asian diaspora – tasteless jokes online, bad headlines, people acting fearfully in public. But if the 2003 SARS epidemic is any model to go by, these strands of xenophobia could potentially escalate into more dangerous, explicit forms of racism.

At the peak of the 2003 outbreak, people of Asian descent were treated like pariahs in the West. There were reports of white people covering their faces in the presence of Asian coworkers, and real estate agents who were told not to serve Asian clients.

Asian people suffered threats of eviction, had job offers rescinded with no explanation, and some Asian Canadian organizations received outright hate messages. Chinese and Asian businesses suffered heavy losses; in Boston, an April Fool’s hoax falsely warned of infected employees at a Chinese restaurant, reportedly causing a 70% drop in the restaurant’s business.

This all happened 17 years ago, when China was still slowly opening up. Now it’s an emerging superpower, and its role in a range of recent conflicts – the ongoing US-China trade war, security concerns surrounding telecommunications company Huawei, allegations of Chinese spies in America and Australia – mean that many in the West already view China with greater suspicion and tension than they did before.

Add the threat of a global pandemic, and a wave of heightened discrimination could be even uglier this time around.

Diaspora communities and local authorities are preparing for this, with many trying to calm fear before it becomes hysteria. In France, the newspaper controversy sparked a social media campaign, with many French Chinese citizens using the hashtag #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus – I am not a virus.

In a statement confirming the first case of coronavirus in Los Angeles this week, the local health department stressed that “people should not be excluded from activities based on their race, country of origin, or recent travel if they do not have symptoms of respiratory illness.”

The head of Toronto Public Health also warned that misinformation about the virus had created “unnecessary stigma against members of our community.”

“I am deeply concerned and find it disappointing that this is happening,” said the head, Eileen de Villa, in a statement Wednesday. “Discrimination is not acceptable. It is not helpful and spreading misinformation does not offer anyone protection.”

Toronto Mayor John Tory also spoke out this week about the coronavirus panic. “Standing with our Chinese community against stigmatization and discrimination,” he said. “We must not allow fear to triumph over our values as a city.”

CNN’s Joe Sutton contributed to this report.