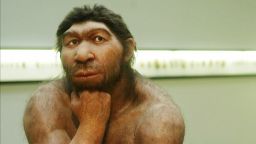

Neanderthals were more resourceful and adventurous than they’re often credited with, according to a new study.

An analysis of clam shells and volcanic rocks from an Italian cave shows that Neanderthals collected shells andpumice from beaches. And due to specific indicators on some of the shells, the researchers also believe Neanderthals waded and dove into the ocean to retrieve shells, meaning they may have been able to swim.

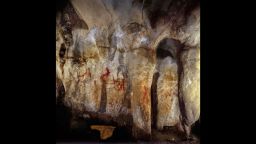

The Grotta dei Moscerini cave is only about ten feet above the beach in central Italy’s Latium region. In 1949, the cave was excavated. The archaeologists recovered 171 clam shells that were modified into sharp tools. They all belonged to a local species called Callista chione, or the smooth clam.

There was evidence that the shells were shaped by stones to make them thin, sharp and resilient. The shells were dated to between 90,000 to 100,000 years ago. This is before the arrival of modern humans in the Western Europe region.

It’s fortunate that the shells, as well as the volcanic rock called pumice, were retrieved from the cave and stored at the Italian Institute of Human Paleontology because the cave itself is no longer accessible. Blasting for coastal highway construction buried the cave in the early 1970s.

The findings from the cave also included a number of pumice stones that the Neanderthals likely used as an abrading tool to sharpen other tools.

Shell tools for Neanderthals are rare, and only a few examples of them have been discovered. The majority of tools associated with Neanderthals involve stone spear tips and stone hammers. But there was even less evidence prior to this study that Neanderthals living in Western Europe dove underwater. The study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS.

“The fact they were exploiting marine resources was something that was known,” said Paola Villa, study author and curator of the University of Colorado at Boulder’s Museum of Natural History. “But until recently, no one really paid much attention to it.”

A new analysis of the shells revealed that 24% of them had smooth, shiny exteriors. They were also larger than the other shells. Both are indicators of fresh shells found on the seafloor, still attached to live clams.

“It’s quite possible that the Neanderthals were collecting shells as far down as 2 to 4 meters,” Villa said, which is the equivalent of about six to 13 feet. “Of course, they did not have scuba equipment.”

The rest of the shells showed evidence of time spent sitting on the beach and experiencing sand weathering.

The shells were modified to be used as scrapers. These were more efficient than thin flinty rocks, which can’t sustain a sharp edge. It’s possible that stone was hard to come by, which is why they sought out shells. Or perhaps the shells suited their needs better, the researchers said.

“No matter how many times you retouch a clam shell, its cutting edge will remain very thin and sharp,” Villa said.

The researchers believe that the pumice stones washed ashore after volcanic eruptions occurred 40 miles south of Moscerini beach.

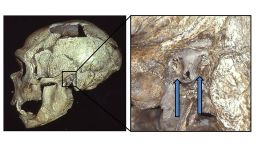

This aligns with evidence from a recent study suggesting that some Neanderthals suffered from “surfer’s ear,” based on bony growths found on the ears belonging to a few Neanderthal skeletons. And previous research has pointed to the fact that neanderthals engaged in fishing.

Other associations between shells and ancient human relatives include shells found alongside Homo erectus fossils in Java, Indonesia, according to the study.

“People are beginning to understand that Neanderthals didn’t just hunt large mammals,” Villa said. “They also did things like freshwater fishing and even skin diving.”