The world’s most disaster-prone region felt the harsh reality of the climate crisis in 2019.

Toxic smog shrouded Asian megacities, hundreds died in flooding and landslides, cyclones battered coastlines and bushfires, droughts and deadly heatwaves led totowns and cities almost running out of water.

Far from being anomalies, scientists say the climate crisis is causing more extreme weather events – and it’s having devastating consequences in Asia and the Pacific.

The “relentless sequence of natural disasters” over the past two years “was beyond what the region had previously experienced or was able to predict,” said a United Nations’ Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) report in August.

“This is a sign of things to come in the new climate reality.”

Rallying calls for climate action have been made in countless forums, summits and pledges this year.

But while many people in developed countries see the climate crisis as an urgent but future problem, for millions living in Asia-Pacific, it’s already touching every part of life.

Those on the front lines say words must now translate into tangible change as the world heads into a new decade.

Asia stands to be impacted the most from climate crisis

The Asia-Pacific region, home to 60% of the world’s population, is one of the most vulnerable areas to the climate crisis.

Compounding the problem is rapid urbanization in many Asian nations, with the pace of development often overtaking proper infrastructure planning.

Population booms and the mass migration of people to cities for work is putting strain onwater and food supplies.

Many big Asian cities, including Mumbai, Shanghai, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, and Jakarta, are coastal and low-lying, making them susceptible to sea level rise and other extreme weather events.

Fast-growing, industrializing and coal-reliant Asian countries are pumping out increasing levels of carbon dioxide emissions, despite efforts by nations such as India and China to move towards cleaner energy.

As material wealth grows, so too does the consumer market and demand for emissions-producing conveniences such as air-conditioning, cars and disposable goods.

While wealthier cities like Hong Kong can afford to disaster-proof– to an extent. At the other end of the scale, poverty-stricken populations are living in some of the most environmentally precarious places on Earth, where extreme weather events could prove disastrous for lives, food production, water sources, economies and infrastructure.

“If we do not take urgent climate action now, then we are heading for a temperature increase of more than 3°C by the end of the century, with ever more harmful impacts on human wellbeing,” said World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas, in a statement. “We are nowhere near on track to meet the Paris Agreement target.”

Sea level rise is happening now

As a resident of the low-lying Pacific Island of Samoa, Tagaloa Cooper-Halo has experienced climate changes first hand.

“Sea level rise is speeding up,” said Cooper-Halo, who is Director of Climate Change Resilience at the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). “We expected sea level rise in about 20 years to be showing the changes. But we are seeing it already now.”

In a landmark report this year, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) confirmed that global sea levels are rising faster than expected.

Increasing greenhouse gas emissions, warming temperatures, melting glaciers and disappearing ice sheets could cause sea levels to rise more than two meters (6.6 feet) by the end of this century if emissions continue unchecked, a study released in May found.

A rise of two meters would displace 187 million people, mostly from Asia, and swamp major cities such as Shanghai. Another study suggested that in Southeast Asia, parts of southern Vietnam and Bangkok could be underwater by 2050.

Adapting to rising sea levels will be a key challenge for Asia-Pacific, according to the UN Development Program. Measures include defending coastlines and infrastructure, restoring mangroves, and identifying areas at risk from flooding.

Cooper-Halo said Pacific nations have already been forced to adapt,installing monitoring stations that measure sea level riseand growing crops more resilient to saltwater.

Diets have already changed as ocean acidification and coral bleaching have reduced fish stocks, she said.

“When resources are not as plentiful as they used to be, it changes your dependency, you become more dependent on processed food and therefore we have to import a lot of processed food so it changes the way that we eat, and it therefore affects our health,” Cooper-Halo said.

Storms and typhoons are getting more intense

About 2.4 billion people – about half the population of Asia – live in areas vulnerable to extreme weather events.

This year, flooding and landslides, triggered by torrential monsoon rains, swept across India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, leaving devastation in each country and hundreds of deaths.

China, Vietnam, Japan, India, Bangladesh, South Korea, Thailand, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, were all hit by tropical storms and typhoons – or cyclones – in 2019, causing dozens of deaths, hundreds of thousands displaced and millions of dollars in damage.

The climate crisis is expected to create higher storm surges, increased rainfall and stronger winds.

Joanna Sustento has been campaigning forclimateaction since Typhoon Haiyan devastated her home in Tacloban, the Philippines, in 2013.

Sustento lost both her parents, her eldest brother, sister-in-law, and her young nephew in the storm – one of the most powerful ever recorded.

“We experience an average of 20 typhoons per year and they are becoming more frequent and intense. What does that mean for the Filipino community? It means damaged homes and livelihood, losing loved ones, losing access to clean food and water, being deprived of your own safety,” she told CNN.

“Whenever an extreme weather event happens, we lose our basic human right to safe, decent, and dignified life.”

Seven out of 10 disasters that caused the biggest economic losses in the world from 1970 to 2019 are tropical cyclones, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

The high economic cost of typhoons can cripple poor countries.

In 2015, Category 5 Cyclone Pam cost the Pacific Island of Vanuatu the equivalent of 64% of its gross domestic product.

All cities vulnerable to typhoons are under pressure to improve infrastructure and properly plan for future growth. Investing in early warning systems has already saved countless lives.

Preparing for more extreme weather costs money and there are calls for rich nations to provide smaller economies with finance and technology to recover from the impacts of the climate crisis.

Sustento said fossil fuel companies also need to do their part – by speeding up the shift to renewable energy.

“We should not allow the fossil fuel industry to continue with business as usual, while we are left with no choice but to live with the ‘new normal’, to count our dead, to search for the missing, and to fear for our future,” she said.

Water shortages set to get worse

As the climate crisis makes rainfall and the annual monsoons – vital for the region’s agriculture – more erratic, droughts and water shortages will become more severe.

The past five years have been the hottest on record and blistering heatwaves – felt this year inJapan, China, India, Pakistan, and Australia – are becoming so intense thata group of MIT researchers suggested some places could becometoo hot to be inhabitable.

This year, India’s sixth largest city Chennai almost ran out of water.

Four reservoirs that supply the city’s almost 5 million residents ran almost completely dry. People queued to fill up cans of water across the city and hospitals had no water for operations or sterilizing equipment.

Across the country, 600 million people are facing acute water shortage – and the crisis is expected to worsen as the Himalayan glaciers melt and India’s bore wells threaten to run dry.

“We have an economy where there’s a population that’s growing and industry that’s growing. So you need 40% more water for industry, you need more water for more people. You need more water for everything,” said Jyoti Sharma, founder and president of FORCE, an Indian NGO.

A new report this month said a quarter of the world’s population is living in regions where water resources are insufficient for the needs of the people – with “once unthinkable” water crises becoming common.

“Water stress is the biggest crisis no one is talking about. Its consequences are in plain sight in the form of food insecurity, conflict and migration, and financial instability,” said Andrew Steer, president and CEO of the World Resources Institute.

In India, proper urban planning and development will be the way forward, according to Sharma.

“Make water systems more efficient, make taps and faucets, irrigation systems more efficient. I think that’s what will save us from the crisis ahead,” she said.

The next ten years

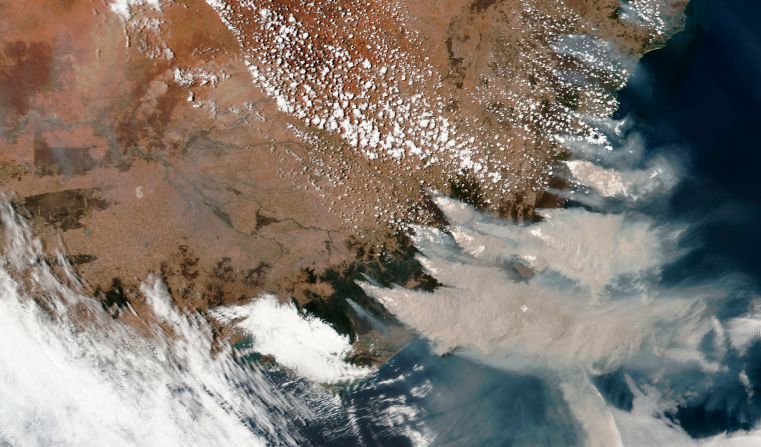

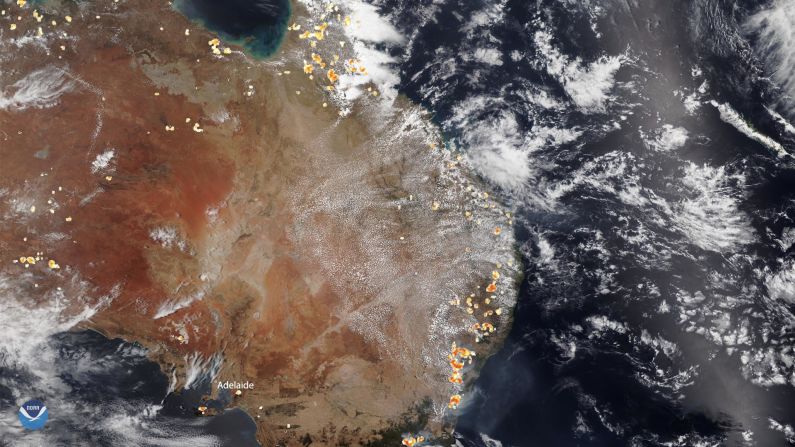

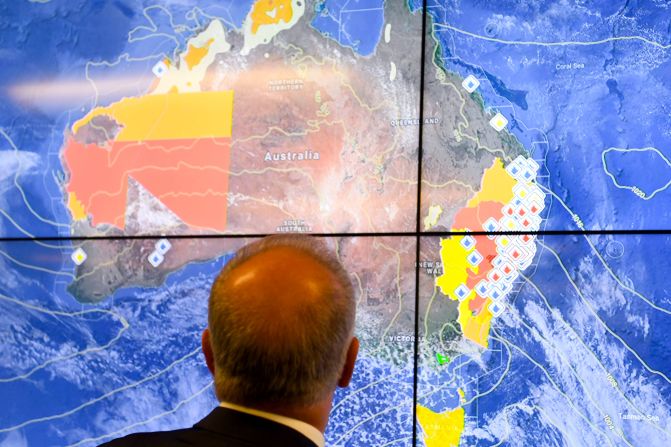

In photos: Bushfires rage through Australia

The world is now 1.1 degrees warmer than it was at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and under current scenarios, carbon dioxide emissions will need to fall by 7.6% every year in the next decade.

Yet emissions are still going up.

The UN Climate Change Conference earlier this month highlighted the huge disconnect between the world’s biggest polluting nations, and the global community demanding change. Many observers, scientists and climate activists called the resulting agreement a failure.

Those impacted by the crisis in Asia don’t have another decade for the rest of the world to get this right.

Surrender is not an option, said Cooper-Halo.

In “the Pacific, the public has woken up to this reality for many years now,” she said. Now, countries need to catch up and step up.