In almost six months of protests, you might be forgiven for thinking Hong Kong had seen it all. And yet, this week brought a new sight: men in suits and women in heels joining with student protesters to defy police in the heart of the city’s business district.

Throughout protests in Central this week, bankers, lawyers and other white collar works have taken their lunch breaks at the front lines, wearing masks and holding umbrellas. In some ways, this was reminiscent of the 2014 Umbrella Movement, when the protest camps became mini tourist attractions – but those coming out in Central weren’t simply rubbernecking, they helped build barricades and transport equipment to those on the front.

They also paid the cost: a Citi banker was reportedly arrested after a dispute with police Wednesday, and other white-collar workers appeared to be among those detained during and after clashes in Central all week.

While there are undoubtedly material causes behind the unrest – not least the extortionate cost of housing – the involvement of well-paid white-collar workers is the latest sign of just how badly the government has misread, or willfully ignored, the depth of antipathy towards it, even as the protests themselves become more violent and disruptive.

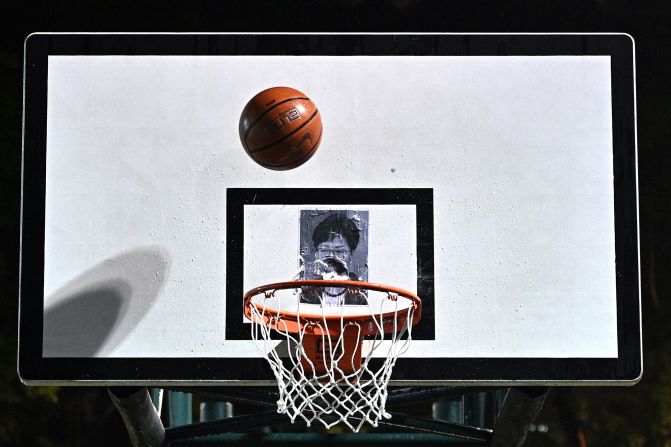

For months now, Chief Executive Carrie Lam and her administration have insisted that support for the protests is waning. The narrative goes that while there was widespread support for withdrawing the extradition bill that started this crisis – as evidenced by multiple large-scale marches that brought the city to a standstill – ordinary Hong Kongers do not approve of the growing violence and vandalism, and want to see a return to normality. This has justified Lam’s hardline policy, which has relied on the police and emergency powers to stem the unrest.

Of course, many Hong Kongers are frustrated by the constant disruption, and worried and sickened by the violence. The incredibly heightened political environment in the city may also be causing some critics to stay silent, for fear of losing friends or family members.

But the evidence that any kind of major shift is happening remains scant, and if there is indeed a silent majority, most of them are just that, silent.

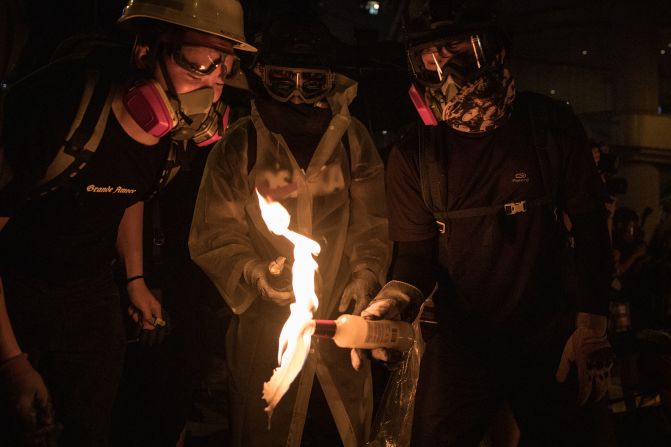

The widespread protests this week, which saw large numbers of bystanders joining in, in both Central and other parts of the city, came after one of the most shocking acts of violence by protesters so far: the dousing of a man in flammable liquid and setting him alight. The incident was caught on camera and shared widely, but while it sparked condemnation and disgust, it does not seem to have sapped support.

Other incidents of violence – including the death this week of an elderly man police say was hit by a brick – or mass destruction have similarly not had the effect on public opinion that might be expected, nor has the fact that the city’s economy is reeling, plunging into recession for the first time in a decade.

This is in part because for every overstep by the protesters, there has been a corresponding one by police: the burning came hours after a protester was shot by a traffic cop, and police further stoked anger by storming the campus of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, even tear gassing the school’s vice chancellor as he tried to negotiate with them.

The death of a Hong Kong University of Science and Technology student after a fall near a protest last week has also been blamed on police, who are accused of temporarily blocking an ambulance from reaching him, something the force strongly denies. Anger over that incident helped drive the protests Monday and Tuesday.

Despite all the evidence before them, Lam and her ministers continue to stick their heads in the sand. Speaking to gobsmacked legislators on Wednesday, the city’s number two official, Matthew Cheung, said he could not understand public anger because there were no public opinion polls available, reportedly saying “people could be upset about various things.”

Putting aside the fact that there are widely respected polls – which show Lam’s plummeting popularity and support for protest demands – the idea that the government should need independent polls to understand the unrest after six months of protests focused on “five demands, not one less,” beggars belief.

In pictures: Hong Kong unrest

Soon the government will have evidence that it cannot ignore however. District council elections later this month have been widely cast as a referendum on the protests – one that many analysts expect to go against the government.

Until then, Lam has doubled down on treating the protests as a security – rather than political – issue, putting ever more pressure on the police, and giving the widely maligned force ever greater freedom to rein the violence in any way they see fit. That tactic appears to have been endorsed by Chinese President Xi Jinping. He publicly met with Lam during a visit by her to China and reiterated his support.

“There however seems to be no obvious pathway to the restoration of anything resembling order in the city,” China analyst Bill Bishop wrote this week. “It appears Xi Jinping has decided to allow chaos to increase, believing that the growing contradictions inside Hong Kong society will ultimately lead to so much anger from most of the Hong Kong populace towards the ‘radical’ protestors that the protests will eventually end.”

That tactic has been followed for months now – but while the violence has continued to grow, most anger remains focused not on protesters, but the government that started all this in the first place.