Los Angeles (CNN)For many Americans, LGBTQ history can be a portal of pain. That's in no small part because it tends to feel so incomplete: lives lived belatedly, lives lost prematurely.

However, at CNN's LGBTQ town hall on Thursday, when nine Democratic presidential candidates went deep on the sorts of issues that often get short shrift, that history not only loomed large over the evening -- it also worked as a palliative for the pain, illustrating how these distinct experiences from the past can positively shape our tomorrows.

"I am here because Bayard Rustin and James Baldwin, proud gay Americans, stood for my rights," Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey said, when discussing the roots of his political activism and how his views have evolved, sometimes significantly, over time.

But these men weren't only gay. By referring to a key architect of the mid-century civil-rights movement and to one of the country's most influential intellectual talents, respectively, Booker was, more specifically, underscoring the oft-overlooked, though no less significant, legacy of gay black Americans. In other words, it was history, inherited -- and it was history, embraced.

The past also surfaced with the memory of Matthew Shepard, the gay 21-year-old who was murdered -- robbed, tortured and tied to a fence -- in 1998. Shepard's mother, a prominent LGBTQ-rights advocate, asked former Vice President Joe Biden what he'd do to protect marginalized communities from hate crimes like the one that took her son's life.

Her question stung, at least in part because it was only in 2009, more than a decade after Shepard's death, that Congress passed -- and former President Barack Obama signed into law -- the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

But it was reassuring that Biden answered the question by pointing to, among other things, the importance of the Equality Act, a wide-ranging bill that would prohibit anti-LGBTQ discrimination across all aspects of commercial and public life. His firm promise, shared by other town hall participants, that the bill would be "first and foremost" on the agenda signaled a much broader desire to fill the gaps in federal law that still exist around queer lives.

Signs of protest

Yet the moments that most visibly brought the queer past to Thursday's town hall were the ones that did exactly what LGBTQ-rights activists famously did half a century ago: protest.

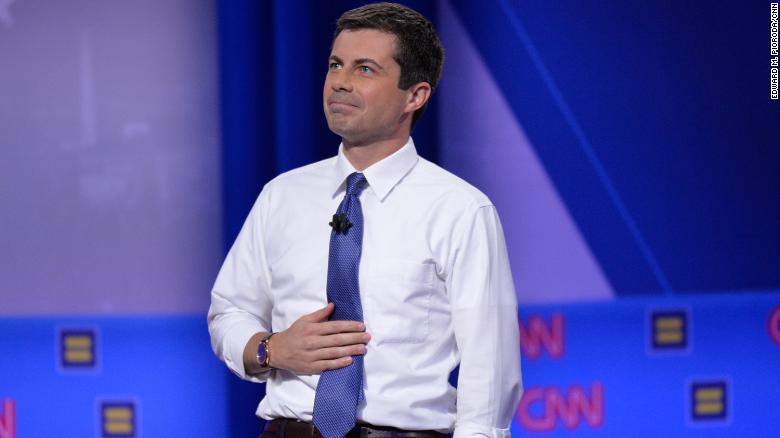

It happened first when Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, took the stage. Demonstrators with signs interrupted to demand greater awareness of the violence plaguing transgender women of color. CNN's Anderson Cooper, who moderated the discussion with Buttigieg, remarked that "there is a long and proud tradition in history in the gay, lesbian and transgender community of protest and we applaud them for their protest."

It happened, too, while former Rep. Beto O'Rourke of Texas was onstage and a woman named Blossom C. Brown took the microphone from a member of the audience.

"Black trans women are dying," she said. (At least 19 transgender people have been killed this year, according to the Human Rights Campaign.)

"Our lives matter. I am an extraordinary black trans woman, and I deserve to be here," she added.

(In another nod to history, California Sen. Kamala Harris mentioned Gwen Araujo, a 17-year-old transgender woman who was murdered in 2002.)

Mirroring Cooper, CNN moderator Don Lemon praised Brown.

"The reason we're here is to validate women like you," he said, at one point handing the microphone back to her.

You could think of the fact that so many Democratic presidential hopefuls attended a town hall so steeped in queer history as a referendum on a status quo that's long elided the community. You could think of it, too, as a kind of permission -- to hope for, and also forge, a new path.