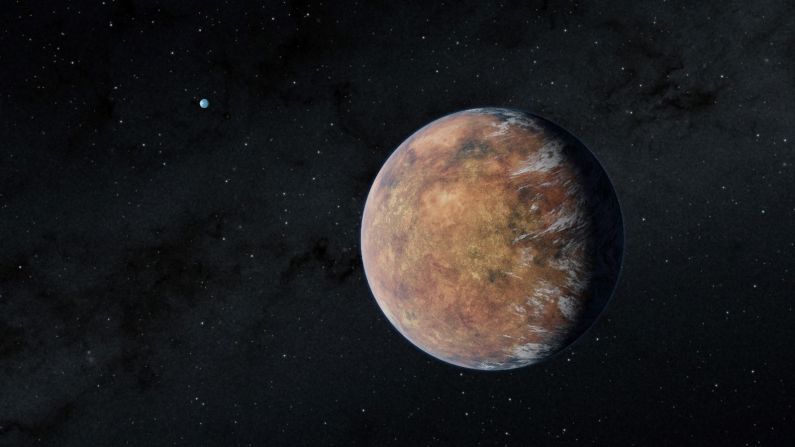

For the first time, astronomers have peered into the atmosphere of an exoplanet – a planet outside our solar system – and discovered both water vapor and temperatures that could potentially support life, according to a new study.

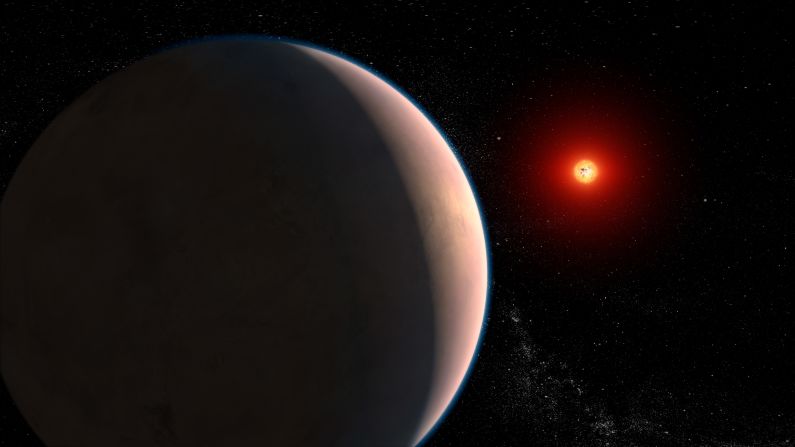

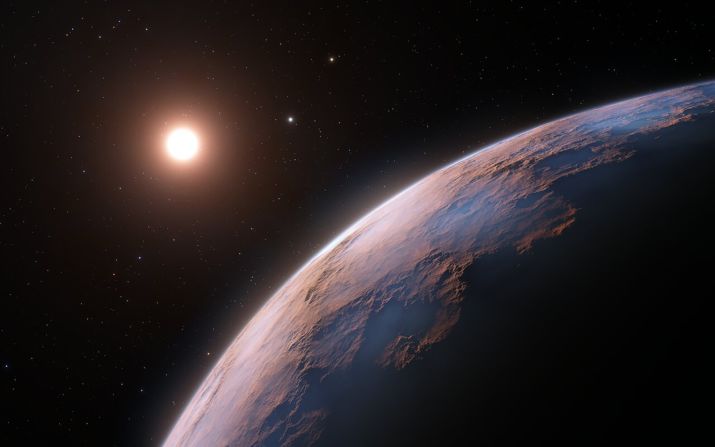

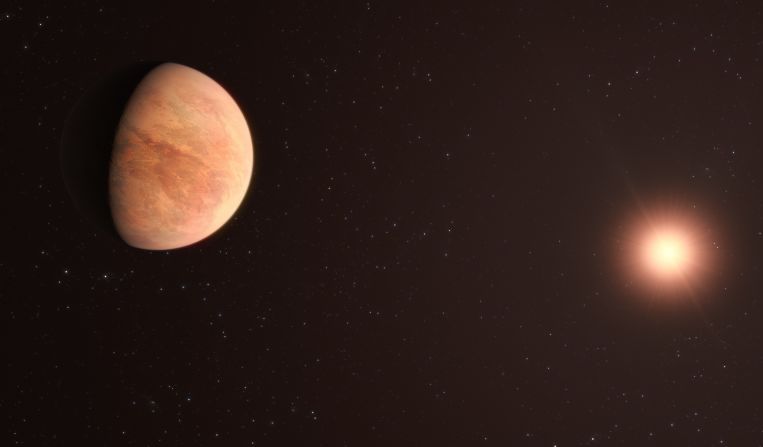

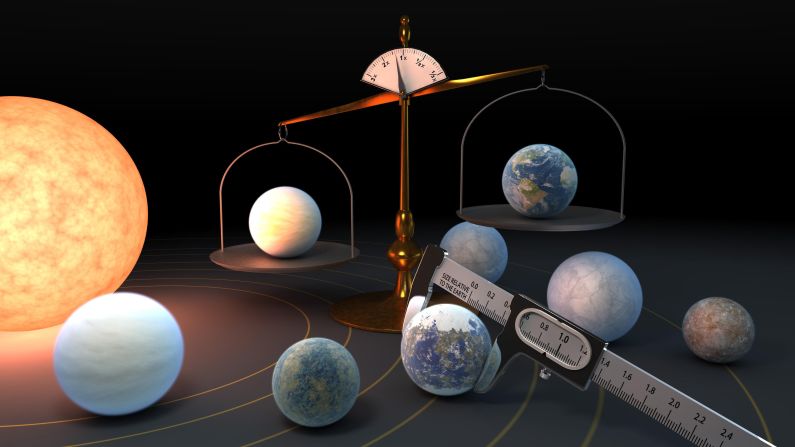

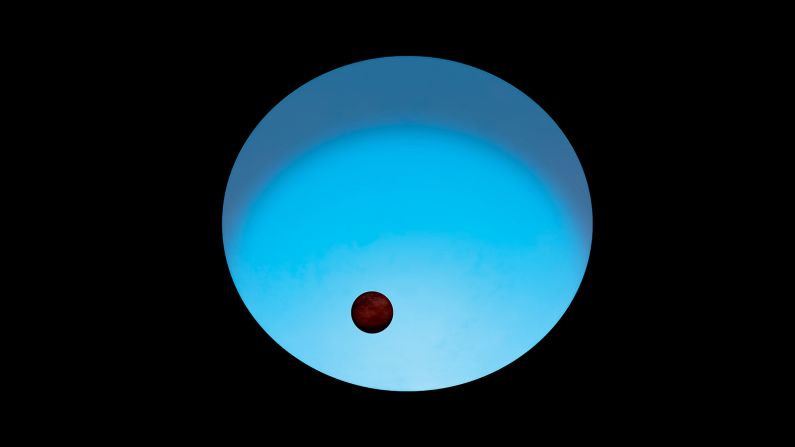

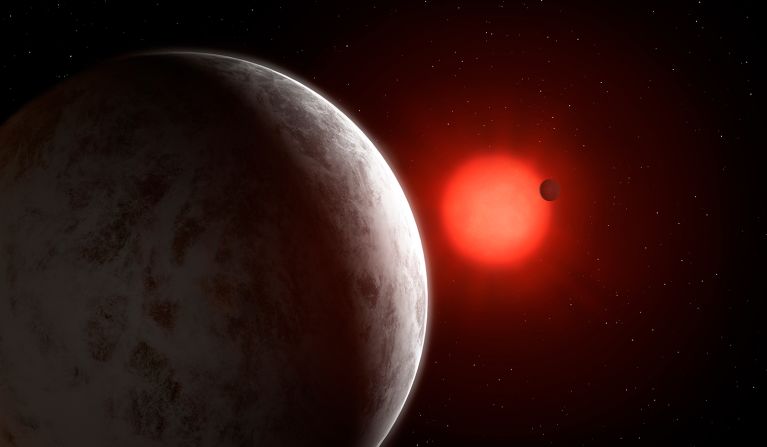

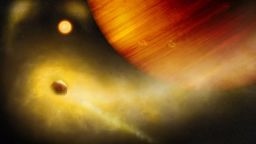

The exoplanet, known as K2-18b, is eight times the mass of Earth and known as a super-Earth, or exoplanets between the mass of Earth and Neptune. It orbits a red dwarf star 110 light-years away from Earth in the Leo constellation. The planet was first discovered in 2015 by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft.

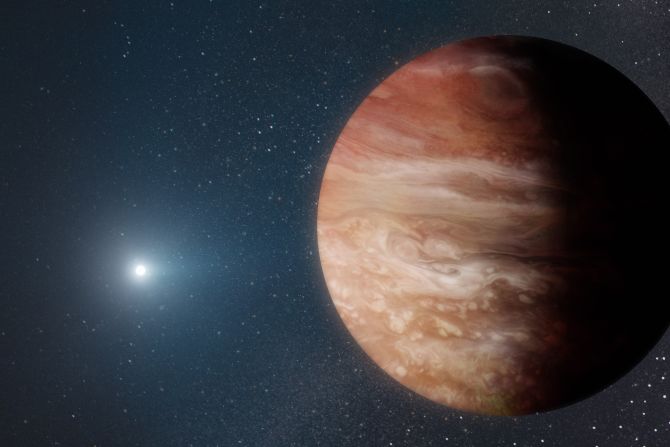

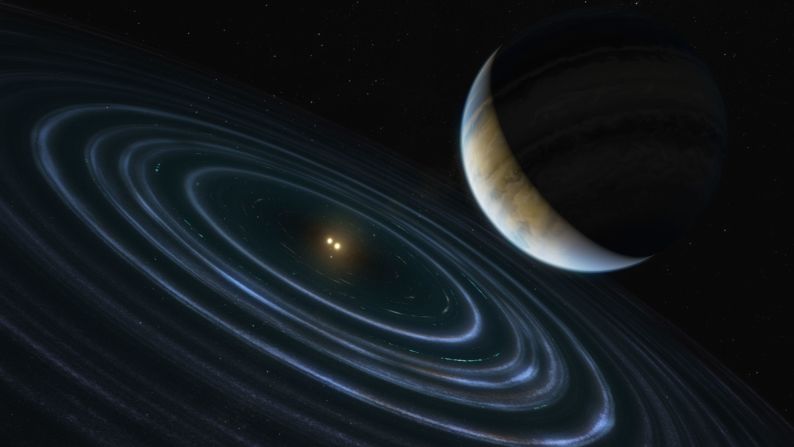

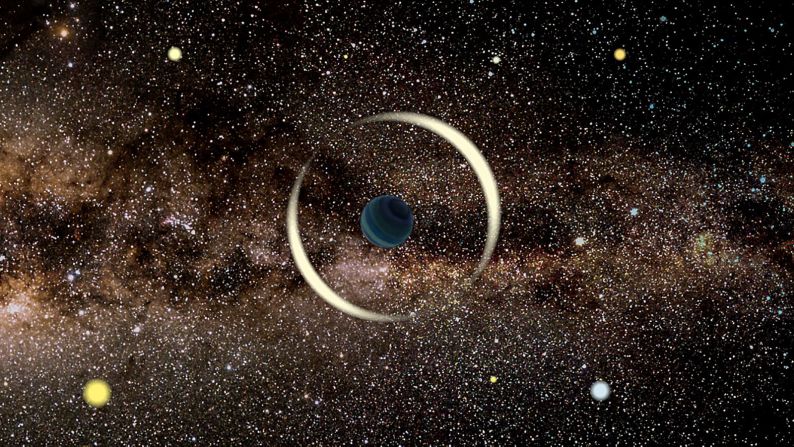

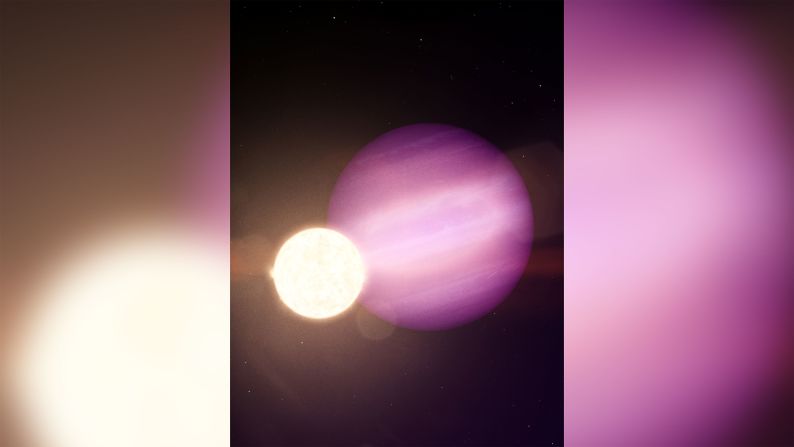

Weird and wonderful planets beyond our solar system

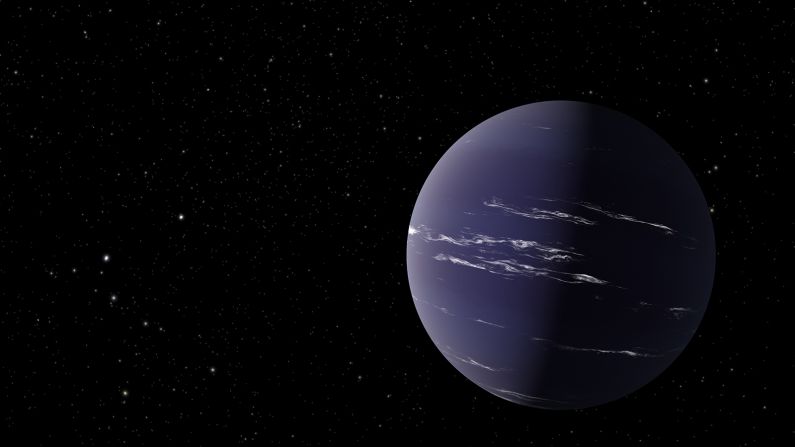

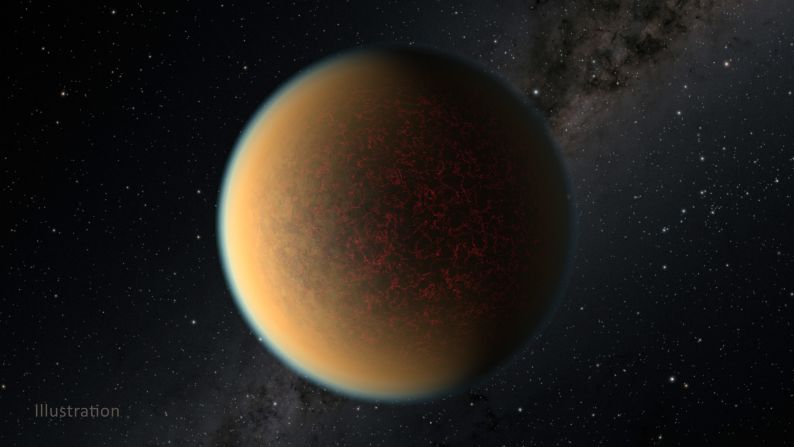

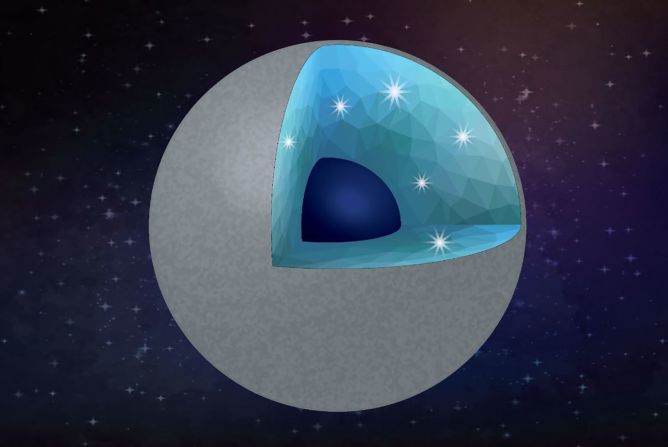

A research team used archival data collected by the Hubble Space Telescope between 2016 and 2017 that captured starlight as it passed through the atmosphere of the exoplanet. The researchers said they clearly saw the signature for water vapor in the atmosphere when they put the data through algorithms. They also observed the signatures of hydrogen and helium in the atmosphere, two of the most abundant elements in the universe.

The detection of water vapor in the atmosphere of this exoplanet is particularly exciting to the researchers because the exoplanet also lies within the habitable zone of its star, which includes the right temperatures for liquid water to exist on the surface of the planet and potentially support life as we understand it.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Nature Astronomy on Wednesday.

“Finding water in a potentially habitable world other than Earth is incredibly exciting,” said Angelos Tsiaras, study author and research associate at the University College London’s Centre for Space Exochemistry Data. “K2-18b is not ‘Earth 2.0’ as it is significantly heavier and has a different atmospheric composition. However, it brings us closer to answering the fundamental question: Is the Earth unique?”

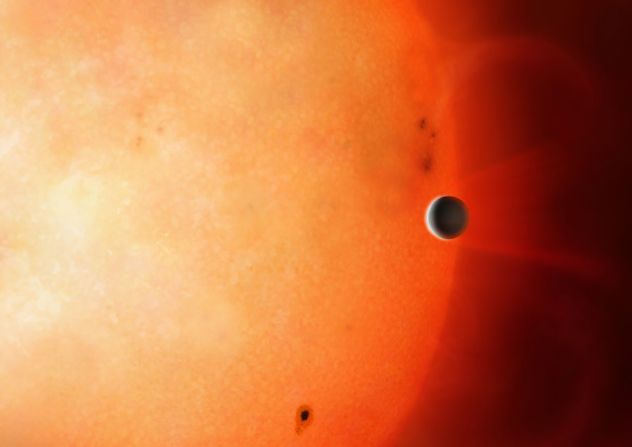

The exoplanet completes one orbit around its star every 33 days and it’s much closer to its star than Earth is to the sun. But the red dwarf star is also much cooler than our sun. Based on the researchers’ calculations, they believe the planet could even be at a similar temperature to that of Earth. But the range extends to include temperatures much colder or warmer than Earth because of the constraints of their data.

The red dwarf star is an active one, however, which is likely exposing the exoplanet to more radiation than Earth receives.

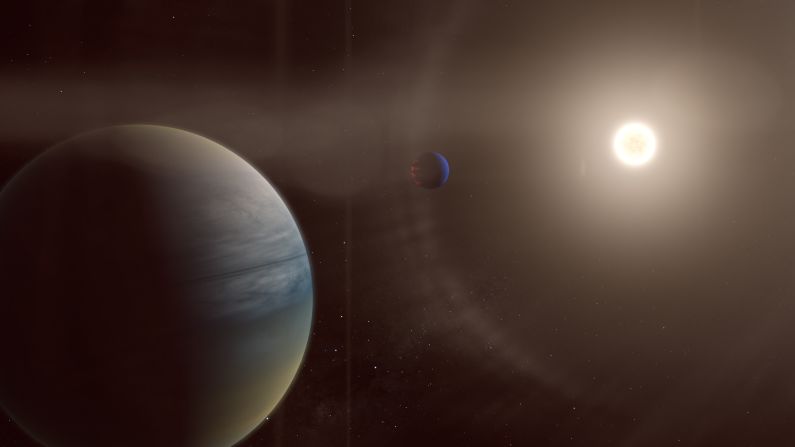

“With so many new super-Earths expected to be found over the next couple of decades, it is likely that this is the first discovery of many potentially habitable planets,” said Ingo Waldmann, study co-author and lecturer in extrasolar planets at the University College London’s Centre for Space Exochemistry Data. “This is not only because super-Earths like K2-18b are the most common planets in our Galaxy, but also because red dwarfs - stars smaller than our Sun - are the most common stars.”

The Hubble Space Telescope is only sensitive to the signature of water, but future telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s ARIEL mission will be able to study exoplanet atmospheres in greater detail with more advanced instruments.

The researchers believe that other elements like nitrogen and methane could also be present in the atmosphere, but only future observations by more advanced telescopes will reveal them.

“Our discovery makes K2-18 b one of the most interesting targets for future study,” said Giovanna Tinetti, study co-author and principal investigator for ARIEL. “Over 4,000 exoplanets have been detected but we don’t know much about their composition and nature. By observing a large sample of planets, we hope to reveal secrets about their chemistry, formation and evolution.”