Banishing an infectious disease from the face of the Earth is the holy grail of public health – a scientific and humanitarian feat for the ages.

It’s also fiendishly difficult.

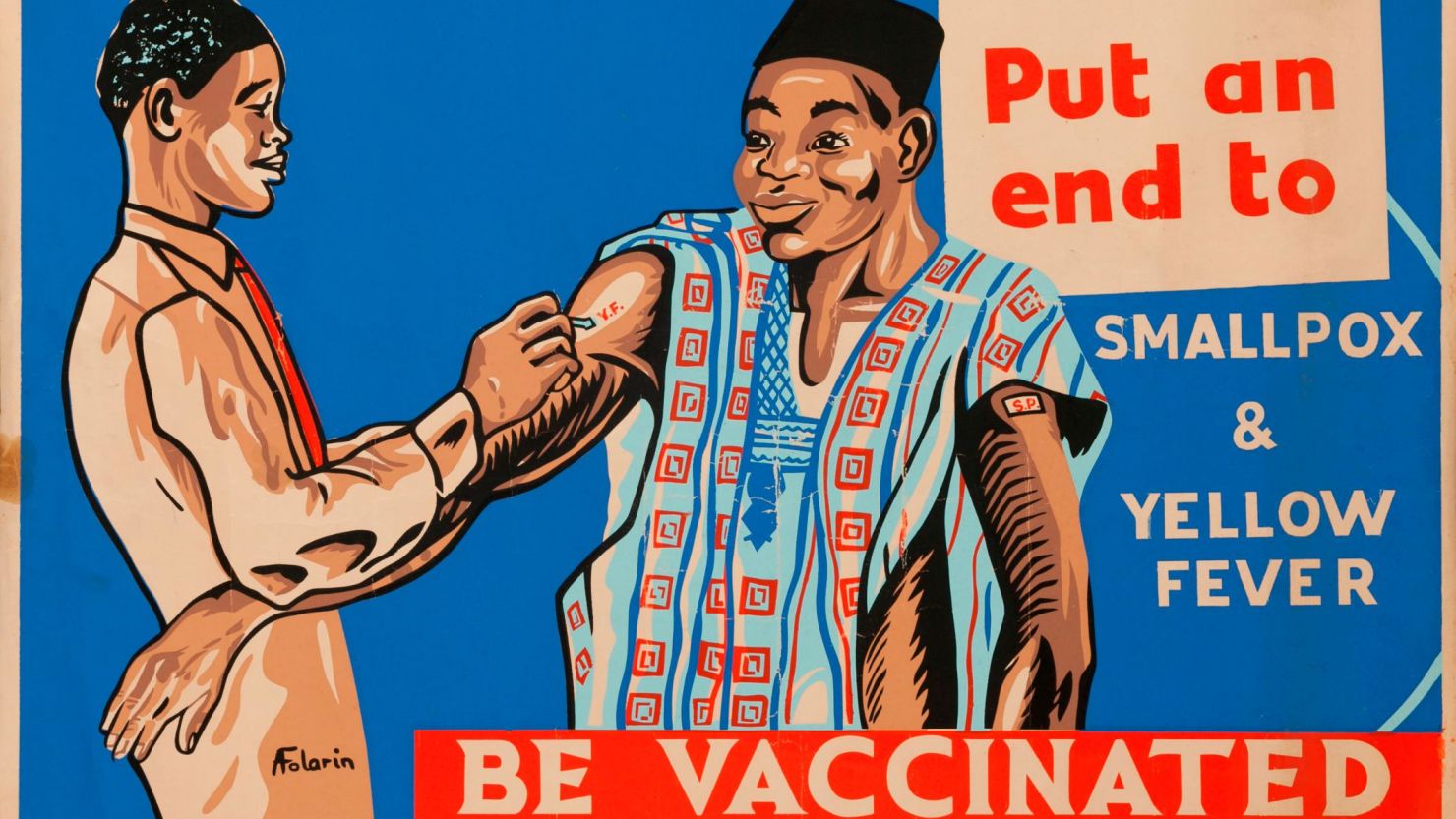

Smallpox, which once killed 2 million people a year and disfigured many more, is the only human disease to have been eradicated. It was a feat achieved in 1979 following painstaking and lengthy vaccination efforts. (Rinderpest, a disease that affects cattle and also led to food shortages in Africa, was eradicated in 2011.)

The world has come close with polio, but the eradication campaign launched in 1998 is nearly two decades past its 2000 deadline, and while the wild polio virus is cornered in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the emergence of new, vaccine-derived strains of the disease have complicated efforts. With some lucky breaks, the disease could be gone by 2023. Still, the resurgence of measles, another disease once thought to be down and out, serves as a cautionary tale.

Likewise, deadlines for the complete eradication of guinea worm disease, a debilitating condition that causes ulcers and swelling until the worm emerges from the feet, have come and gone without success.

Despite this checkered history, many in the global health community have another deadly disease in their sights: Malaria, which kills 400,000 a year, the majority children younger than 5.

A landmark report by 41 of the world’s leading malariologists, biomedical scientists, economists and health policymakers released on Sunday calls for a world free of malaria by 2050 and sets out in detail the case for and path to eradication.

It comes 50 years after a first attempt failed.

“For too long, malaria eradication has been a distant dream, but now we have evidence that malaria can and should be eradicated by 2050,” said Sir Richard Feachem, co-chair of The Lancet Commission on malaria eradication and director of the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco.

Complex enemy

It’s an ambitious goal.

As a parasitic disease transmitted through the bite of the female mosquito, malaria is a much more complicated to tackle than smallpox or polio viruses, both relatively simple organisms. The parasite goes through many different changes during its life cycles in both its human and insect hosts.

10 diseases you thought were gone

And unlike polio and smallpox, a vaccine looks less likely to play a key role in its plotted demise. While a malaria vaccine is undergoing a large trial in three African countries, Feachem said that the jury was still out on whether that would be widely useful and that the commission’s report “foresees malaria eradication without a vaccine.”

“We, the public health community, have had high expectations of malaria vaccines for 40 years and spent a lot of money trying to develop them,” he said. “But the commission cautions against spending too much money on vaccine research where the vaccines people have in mind do not confer significant advantages over the vaccine we already have.”

Instead, the report says eradication will rely on new drugs, diagnostics and insecticides in the pipeline to overcome the growing problem of resistance to malaria drugs and the insecticides used to impregnate things like bednets.

“There’s this evolutionary arms race between the parasite and our ability to keep on top of its evolving biology.” Feachem said. “At the moment we’re staying ahead of the evolutionary arms race but there’s no certainty we can do that decade after decade. It’s an argument that impels us to have a sense of urgency about this.”

New technologies like gene editing also offer the promise of genetically modified mosquitoes that fight the others but while the science is there, Feachem said applying it in a real-world setting is likely a decade away, given the regulatory and ethical concerns of releasing a genetically modified creature into the environment.

There are also wild cards like monkey malaria to contend with. Malaysia has come close to eliminating human malaria, but has seen thousands of people infected with a species of monkey malaria parasite.

Overcoming ‘a sense of defeat’

The world first tried to eradicate malaria soon after the World Health Organization was founded in 1948. The program that lasted from 1955 until 1969 rid several countries of the disease, but it was not implemented in sub-Saharan Africa, the region most affected.

“Falling short of eradication led to a sense of defeat, the neglect of malaria control efforts and abandonment of research into new tools and approaches,” the WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group on Malaria Eradication said in its summary of a three-year review released on August 23.

“Malaria came back with a vengeance, millions of deaths followed. It took decades for the world to be ready to fight back against malaria.”

Huge progress was made between 2000 and 2015, with a 62% reduction in malaria deaths, according to WHO, and a 41% reduction in the number of cases. However, progress has stalled and more recent data suggests that malaria is making a comeback, with 219 million cases in 2017, compared with 217 million in 2016.

While WHO said it remains deeply committed to the disappearance of the malaria parasite, the review suggested it was premature to put a date on it, concluding that the disease would not be eradicated with the currently available drugs and tools – even though eradication would save millions of lives and a return on investment of billions of dollars.

“Even with our most optimistic scenarios and projection, we face an unavoidable fact: using current tools, we will still have eleven million cases of malaria in Africa in 2050,” the report said.

“In these circumstances, it is impossible to either set a target date for malaria eradication, formulate a reliable operational plan for malaria eradication or to give it a price tag.

“We must not set the world up for another failed malaria eradication effort that could derail attempt to achieve our vision.”

Moonshot?

While many of the challenges that existed when the first eradication program was abandoned are similar to those today, Feachem said that our ability to respond to those challenges was “completely transformed.”

“We’re now poised at this moment where we can take a cool-headed look at the progress we’ve made, the tools that we have in our hands and what’s in the pipeline,” he said.

“To achieve this common vision, we simply cannot continue with a business-as-usual approach.”

In addition to new drugs and technological innovations, one thing that will help “bend the curve” is better management of eradication programs – something that’s been enabled by better quality and time-sensitive data. In countries like Sri Lanka and China, which hasn’t had a case of malaria since 2016, it has allowed authorities to move away from a one-size-fits-all national approach and tailor interventions to specific areas.

Money, of course, also plays a role and the commission report estimates than an extra $2 billion spending on malaria will be needed per year globally to rid the world of the disease.

Feachem dismisses critics that say now isn’t the time to push for an eradication date and instead health authorities should get back on track to meeting existing goals like lowering Malaria cases and mortality by 90% by 2030.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“The commitment needs a time line and without one the commitment isn’t totally serious,” he said.

“If President Kennedy had said in 1961, we will walk on the moon as soon as we can work out how to do it, we would never have walked on the moon by 1969.

“But … he said we’ll walk on the moon before the end of the decade and it’s that combination of a commitment with a timeline that is so powerful.”