India is one step closer to achieving its space superpower ambitions. If the Chandrayaan-2 lunar mission successfully touches down on Friday, the country will join the United States, China and the former Soviet Union in an elite club of nations that have made a soft landing on the moon.

And if all goes to plan, India will become the second country after China to explore the far side of the moon. The mission, operated by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) was launched last month. After more than 45 days it is scheduled to land a rover on the lunar surface on September 7.

“This mission has proved beyond doubt, once again, that when it comes to attempting an endeavour in new age, cutting edge areas, with innovative zeal, our scientists are second to none. They are the best … they are world class,” said Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a radio address in July.

The Chandrayaan-2, which means “moon vehicle” in Sanskrit, took off from the Satish Dhawan Space Center at Sriharikota in southern Andhra Pradesh on July 22. Weighing 3.8 tons and carrying 13 payloads, it has three elements: lunar orbiter, lander and rover.

After traveling for two months, the Chandrayaan-2 positioned itself in a circular orbit 62 miles (100 kilometers) above the moon’s surface. From there, the lander – named Vikram, after the pioneer of the Indian space program Vikram Sarabhai – will separate from the main vessel, and Friday (Saturday morning India time) will make its landing on the moon’s surface near its south pole.

A robotic rover named Pragyan (meaning “wisdom”) will then be deployed, spending one lunar day collecting mineral and chemical samples from the moon’s surface for remote scientific analysis.

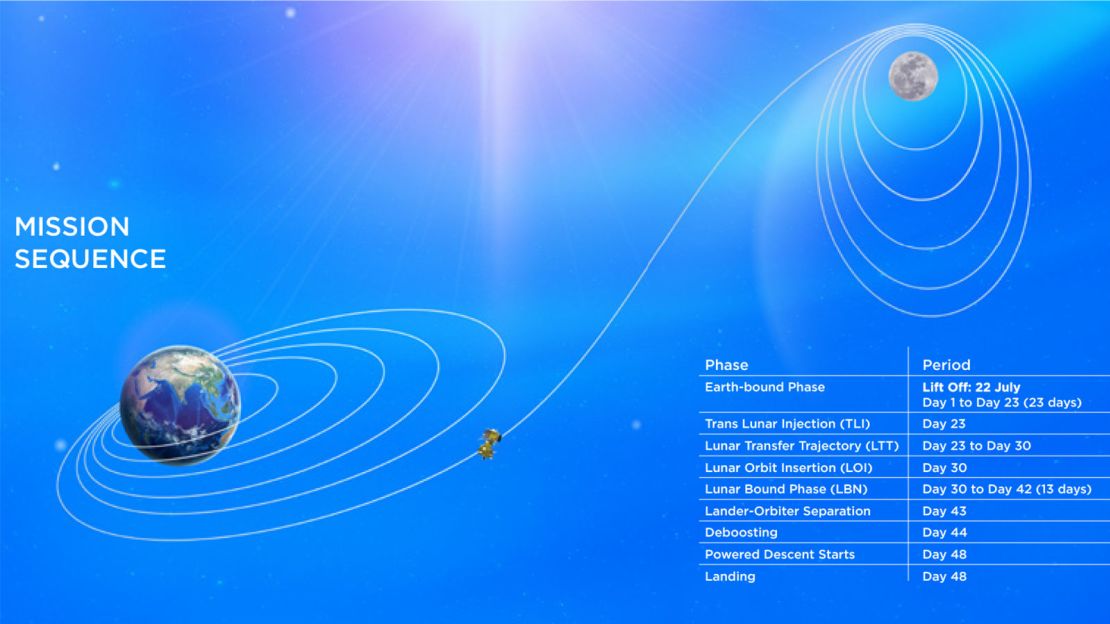

Chandrayaan-2 circled the Earth multiple times over the last month to increase its orbital height enough to place itself in the trajectory to launch into the lunar orbit. The propulsion system of Chandrayaan-2 slowed it down a little to allow it to be captured into an orbit around the moon. Using a series of maneuvers, it lowered itself in steps toward the moon to finish the de-orbiting Wednesday.

Each step has been carefully planned and executed by ISRO on a tight budget. The Chnadrayaan-2 mission comes at less than half the amount spent on the recent Hollywood blockbuster “Avengers: Endgame,” which cost $356 million to make.

Over the next year, the orbiter is expected to map the lunar surface and study the outer atmosphere of the moon.

“It is really a glowing testimony to the rapid advances the country has been making in science and technology in the last few years,” said India’s Vice President M. Venkaiah Naidu.

A new, cost-effective space superpower

India’s entrance into space exploration over the last decade has been marked by a series of missions at low operational costs.

ISRO tends to utilize the talent it has in-house and saves money on not hiring contractors. Also, the missions do not last very long, just a few years each. And India is able to utilize the infrastructure already put in-place by its American counterparts, said Chaitanya Giri, a fellow at the Space and Ocean Studies Programme at Gateway House, the foreign policy think tank.

India has steadily built its reputation in Asia by offering low-budget shuttles for satellite launches in the region.

In 2017, India broke a world record when it launched 104 satellites in one mission, while operating a low-cost budget. Earlier this year, Modi announced that India had shot down one of its own satellites in a military show of force, making it one of four countries to have achieved that feat.

Leaving the Earth’s orbit in 2014, India became the first Asian nation to reach Mars, with its Mangalyaan probe. India’s Mars Orbiter Mission cost just $74 million, less than half of NASA’s $187 million to launch the Mars-bound Maven orbiter in 2013.

In 2008, Chandrayaan-1, India’s maiden lunar mission, discovered water molecules on the surface of the moon. As part of that mission, an impact probe crashed into the moon’s south polar region.

Chandrayaan-2 is a far greater technical challenge than the controlled crash of its predecessor.

“We are doing an unmanned mission … but even so, these are complex missions for a country like India. We are still a small space power and we would require to play with other major space powers,” said Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, head of the nuclear and space policy initiative at the Observer Research Foundation.

Both missions are the building blocks for Chandrayaan-3, scheduled to make a return mission to the moon in 2023 or 2024.

By 2022, India plans to launch a manned mission into space. The Chandrayaan missions are seen as building blocks to that plan.

A regional rival

In a global effort to demonstrate capabilities and tap into the economic gains which are expected to come from space exploration, several countries, along with private sector companies, are racing to discover more about Earth’s only satellite.

“Exploration itself is a big business. It has big economic returns … to build instruments that can look out for minerals, that can look out for important fuels like water or Helium 3,” said Giri.

But can India compete with its space rival, China?

“Maybe that is a part of the ambition,” said Rajagopalan, “but I don’t know whether we have the capacity and the overall wherewithal to compete directly one-on-one [with China]. The reality is that there is a sort of slow and budding competition that is picking up in the Asian context.”

Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has invested billions into the country’s space program. In January, China made history by becoming the first nation to land a rover on the far side of the moon and a planned mission next year is due to land on the moon, collect samples and return to Earth.

Beijing plans to launch its first Mars probe around 2020 to carry out orbital and rover exploration, followed by a mission that would include collection of surface samples from the Red Planet.

China is also aiming to have a fully operational permanent space station by 2022, as the future of the International Space Station remains in doubt due to uncertain funding and complicated politics.