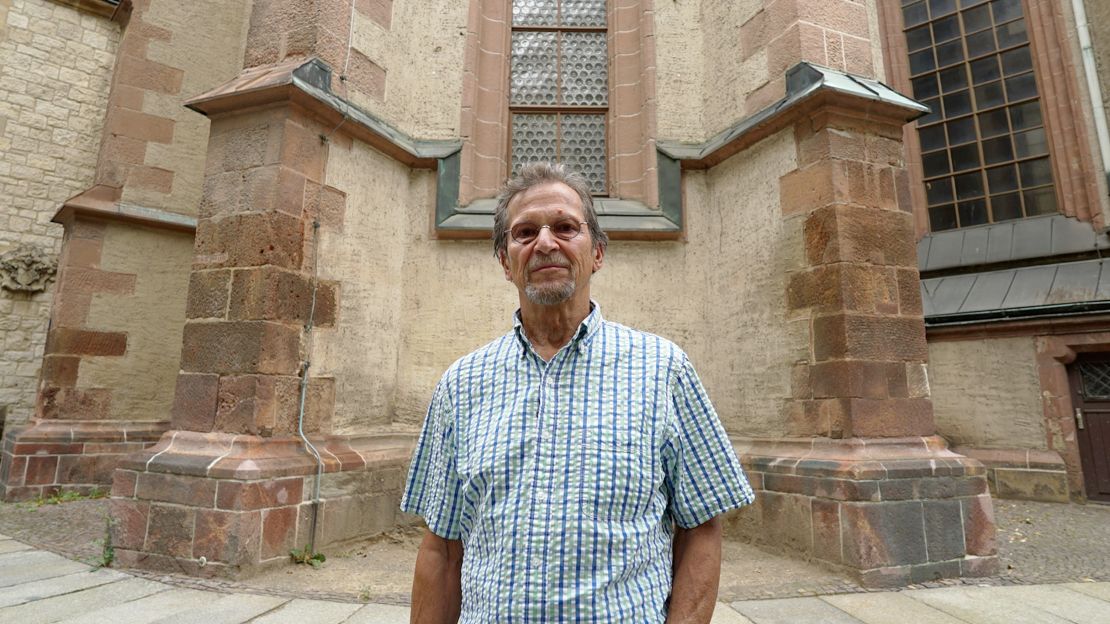

It’s a humid August afternoon and Jörg Kühne gazes across a public square where children squeal and splash in an ankle-deep fountain.

All around him people go about their business: a farmers’ market is in full swing, a tram trundles past, cyclists weave between meandering tourists.

“It wasn’t like this,” Kühne says, squinting against the summer glare. “It was like the black and white photos. It was dark.”

Thirty years ago, this sprawling concrete square in the former East German city of Leipzig was the epicenter of freedom demonstrations that swept the country and brought down the Berlin Wall.

Grainy images of 70,000 protesters in Leipzig carrying candles and chanting “Wir sind das Volk” – “We are the people!” – were beamed across the world on October 9, 1989. The rally was a turning point in the fall of the Iron Curtain a month later.

Kühne was one of the demonstrators who, in his words, “longed for a free and united country.” Then a 21-year-old locksmith working at the state railway company, he said the uprising in his hometown was “the greatest thing I’ve ever experienced.”

Today he is again drawing inspiration from Germany’s peaceful revolution – this time, as a member of the country’s far-right Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) party.

Kühne is a candidate in the upcoming Saxony state election on September 1, where the AfD is tipped to come in at second place, behind Chancellor Angela Merkel’s center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party.

Now the AfD is repackaging the 1989 Leipzig demonstrations for its 2019 political campaign – resurrecting the same slogans, images and revolutionary rhetoric.

From billboards showing historic photographs of the protest, to posters emblazoned with the famous slogan: “We are the people!” the AfD is urging voters in the east to rise up, much as they did against communism three decades ago.

Back then, protesters wanted to tear down the wall dividing their country. The east was eager to embrace western democracy and its promise of free elections, travel and a functioning economy.

Fast forward to 2019 and the AfD is pledging to barricade the nation against Europe’s open borders, playing on fears around migrants and world markets. This nationalist message has struck a chord in Saxony, and other states in former East Germany, where support for the AfD is the strongest in the country.

My grandfather would ‘turn in his grave’

Today a man in his 50s and quick to make jokes about his weight, Kühne paints a picture of similiar activists-turned-AfD supporters who have been sidelined for too long.

“We were not asked” about replacing Germany’s national currency with the euro, or Merkel’s so-called open-door policy on refugees, he said. “But we are the people. And of course my party still uses this wonderful slogan from the peaceful revolution today.”

Indeed drive along the highway between Berlin and Leipzig and you’ll see dozens of AfD billboards declaring “We are the people!” and referring to the protest date in 1989.

Another billboard says “The East is standing up!” and in smaller print, “Change 2.0.”

The posters imply that “if voters opt for the AfD, they can finish the work of those who led the peaceful revolution,” said Kristina Spohr, a historian and the author of “Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989.”

“This is an abuse of history,” she added. “What the AfD wants – a nationalist, inward-looking Germany – has nothing to do with what the people wanted in 1989.”

The AfD’s rebrand hasn’t gone down well with everyone in Leipzig, a city that has a reputation as a liberal stronghold in conservative Saxony.

Martin Neuhof’s grandfather was a photojournalist during the 1989 demonstrations. His picture showing thousands of people flooding what was then Karl-Marx-Platz was used in AfD billboards during local elections in May.

Splashed across the photo were the words “Change for Leipzig,” and the AfD logo.

“If my grandfather knew about it, it would make him turn in his grave,” said Neuhof of Friedrich Gahlbeck, who passed away 20 years ago.

The AfD is “instrumentalizing the peaceful revolution in Leipzig,” said Neuhof, who as a child spent hours developing photos in the darkroom alongside his grandfather, who worked for the East German state news agency.

It inspired Neuhof’s own career as a photographer in Leipzig, where he runs the anti-racism photo project “Herzkampf” – meaning fighting from the heart – featuring portraits of local activists.

Neuhof’s family is now in a legal battle with the AfD over its use of the historic photo. Kühne says proceedings are “ongoing” but he thought it was a “wonderful idea” to use the photo in the political campaign.

It certainly didn’t hurt his own campaign – Kühne was elected one of Leipzig’s city councillors. And is now one of 11 AfD members in the left-leaning council.

‘They thought everybody would be driving a Mercedes’

Reminders of the revolution are everywhere here. A giant mural painted on the wall of Leipzig’s Marriott Hotel depicts the 1989 protest in brilliant rainbow colors.

Gisela Kallenbach is a retired Green politician who also took to the streets three decades ago. She points to the cartoon characters featured on the mural and echoes Kühne’s words – “It wasn’t like this. It was dark.”

Protesters were engulfed in air “choked with smoke” from nearby lignite factories, remembers Kallenbach who was then a 47-year-old chemical engineer and mother-of-three.

When the Berlin Wall finally did come crashing down, so did a lot of East German aspirations. Some had “illusions that everybody would be driving a Mercedes,” Kallenbach said.

The rallying cry of “We are the people!” was replaced with “We are one people!” but the reality didn’t quite meet expectations, Spohr, the historian, said.

Very quickly, feelings of freedom gave way to feeling like second-class citizens. “Basically the West German political system [was] applied to all of Germany,” she said. “Everything that was tied to an East German identity was basically binned,” Spohr said.

By 1991, Spohr said the country was seeing a rise in far-right parties.

Saxony and the neighboring eastern German states of Brandenburg (which also heads to the polls on Sunday) and Thuringia are fertile ground for the AfD. These are working class regions, hit by the closure of their coal industries, and still lagging behind the west in employment and salaries.

While the AfD took 12.6% of the vote nationally during the 2017 general election, it was double this in Saxony, where it had 25.4%. It is now the largest opposition party in Germany’s parliament.

Look further right, and you’ll find other movements recycling the slogans of 1989. The anti-Islam group Pegida chanted “We are the people!” during demonstrations in neighboring Dresden in 2015, and held rallies against Muslims every Monday night – a twisted version of the Monday peace prayers in Leipzig all those years ago.

The slogan was resurrected by protesters during violent demonstrations against refugees in the city of Chemnitz, also in Saxony, last year that made headlines around the world.

‘People forget what they have gained’

The AfD, like many populist parties surging in Europe, has directed much of its fury at the European Union.

Kallenbach, who was a member of the European Parliament for years, was quick to defend the EU, though she admitted that German leaders made “mistakes” in the reunification process.

“I think people forget what they have gained in the last 30 years … a free, democratic state,” said Kallenbach, today in her 70s with a shock of brilliant red hair, chunky earrings dangling in agreement.

Life in East Germany was drenched in fear and intimidation. Kallenbach has no photos of herself at the momentous demonstrations, because she was so terrified of being targeted by the Stasi. The shadow of Tiananmen Square loomed large, and she was painfully aware of the tanks lining Leipzig’s streets.

East Germans of all ages were asking for “basic human rights,” she recalled – things like freedom of speech, media and travel, that had been squashed following World War II.

Now Kallenbach is determined to ensure the AfD doesn’t turn back the clock on those hard-won freedoms, jumping on her bicycle to hand out anti-far right flyers in the state election.

The shocking pollution in East Germany was one of the reasons Kallenbach hit the streets all those years ago. Today it is the AfD “poisoning the atmosphere in our society,” she said.

“Listen to the statements of their leaders. They are … racist, nationalistic. They provide an atmosphere you can almost compare to the 1930s,” she said in reference to Nazi Germany. “I don’t want to live in a country where this rhetoric is the common language.”

Kühne from the AfD dismissed the comparison with a dark time in German history, adding “I completely reject the catchword ‘racism.’”

“People can protest against the AfD,” he said. But they “should not attack us – physically or verbally. We are open to a critical dialogue.”

‘We will see who the people are’

When fellow 1989 demonstrator Christoph Wonneberger nimbly alights from his bicycle, it’s something of a shock to learn he’s 75.

The former pastor looks up at Leipzig’s looming St. Nicholas Church, where he helped organized Monday peace prayers that morphed into the biggest protest movement the East had ever seen.

From the early-1980s, each week people would gather at the grand church to discuss causes close to their hearts. As the threat of nuclear war increased, so did the number of patrons.

By October 1989, more than 2,000 people were packing into the church, with thousands more spilling out into the streets.

The demonstrators were determined not to act aggressively, not to give the police any reason to crack down. Wonneberger believes this non-violent approach – along with their massive numbers – was the secret to their success.

He recalled how “We are the people!” actually came about. During one march, there was a confrontation with police where one of the streets was blocked off. “The police shouted through the loudspeaker, ‘We are the police!’ And the protesters replied: ‘We are the people!’”

“Let’s wait and see at the next election who ‘the people’ really are,” said Wonneberger.