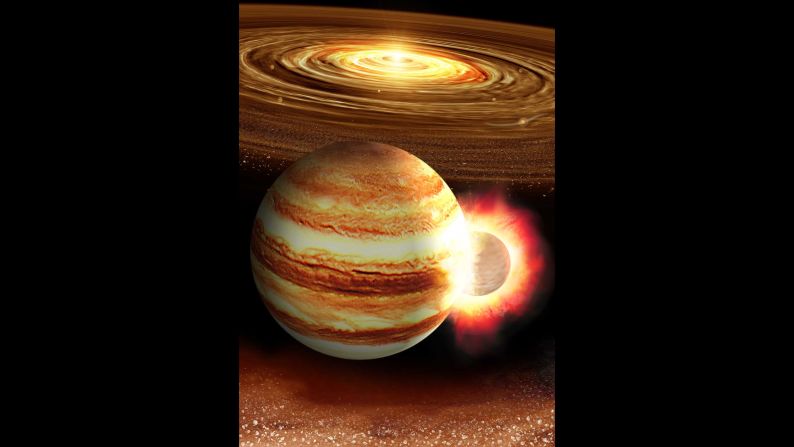

When Jupiter was still forming 4.5 billion years ago, something giant likely crashed into the planet and disrupted the process, according to a new study.

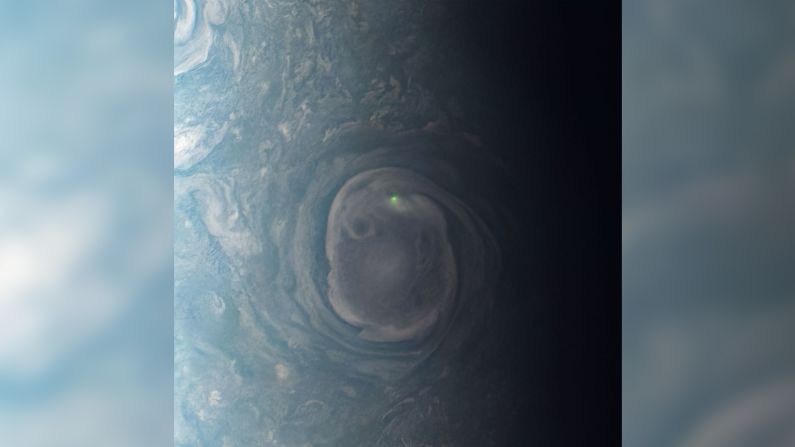

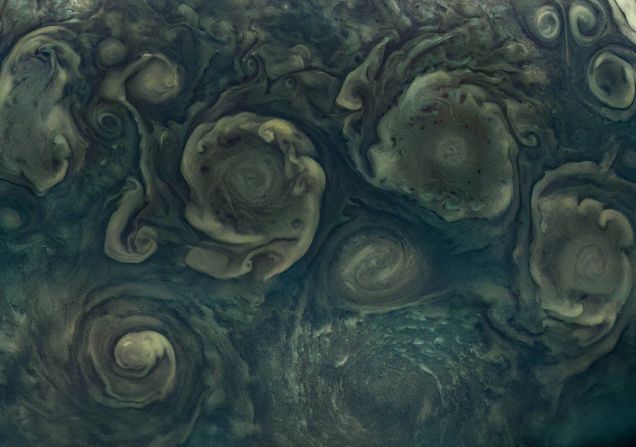

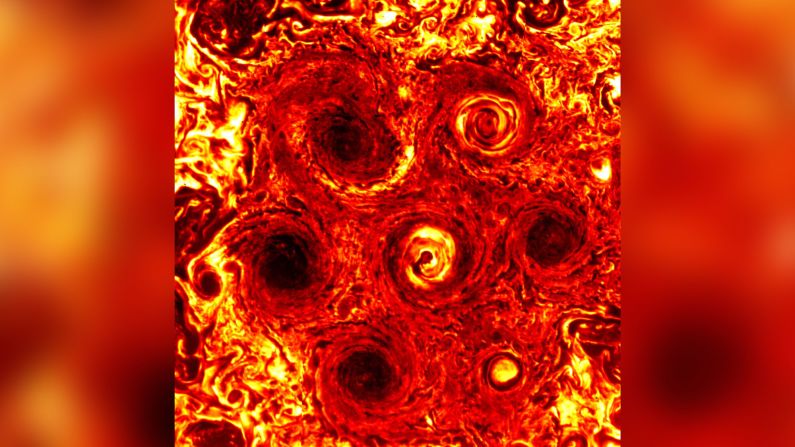

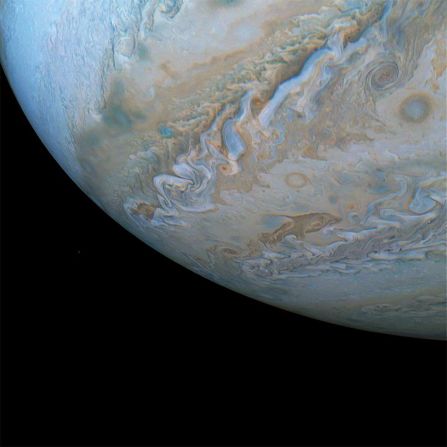

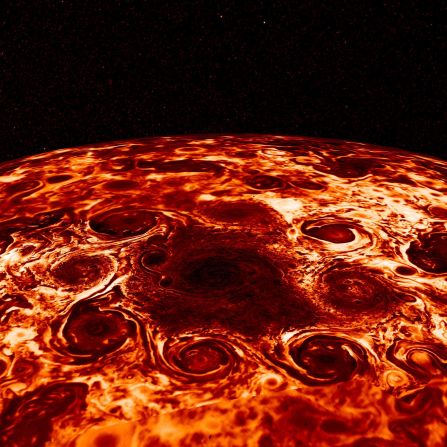

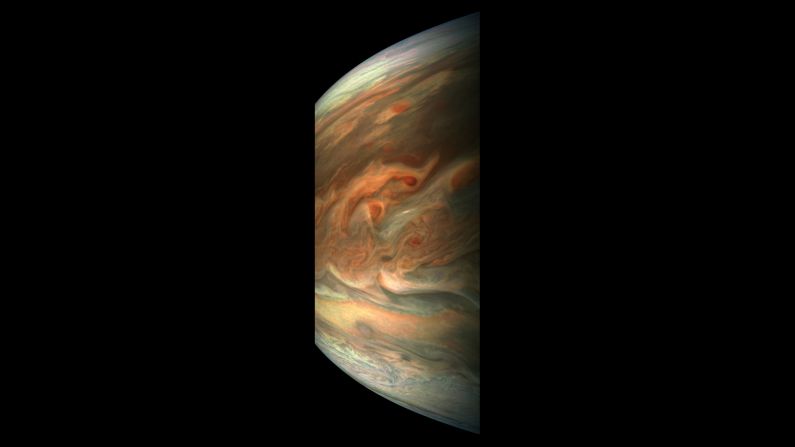

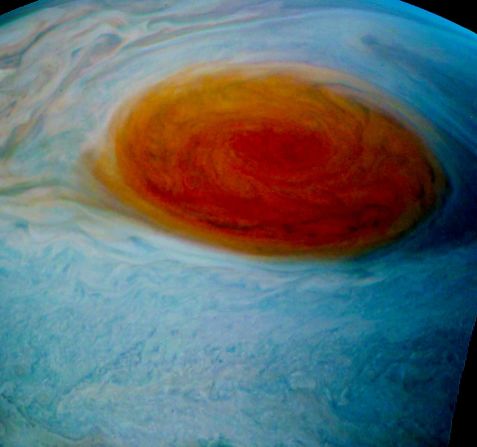

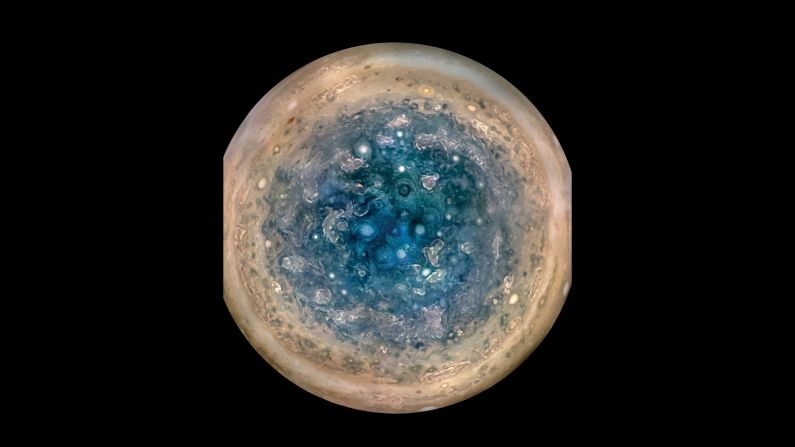

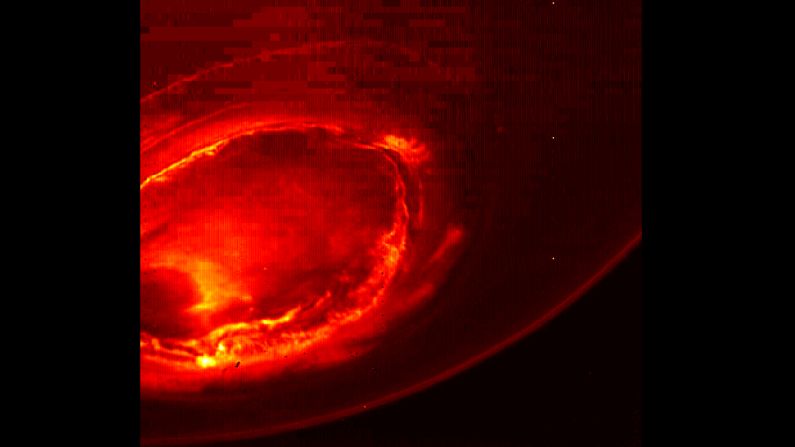

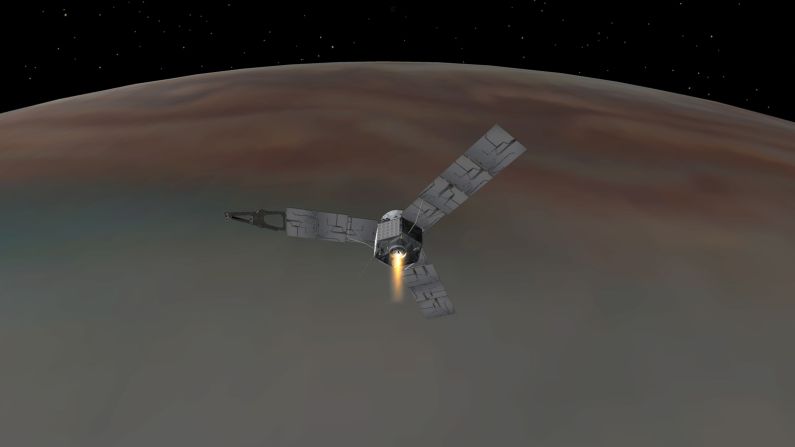

NASA’s Juno spacecraft began orbiting Jupiter in July 2016. In addition to capturing stunning imagery of the gas giant, Juno has also uncovered surprising insight that only creates more questions.

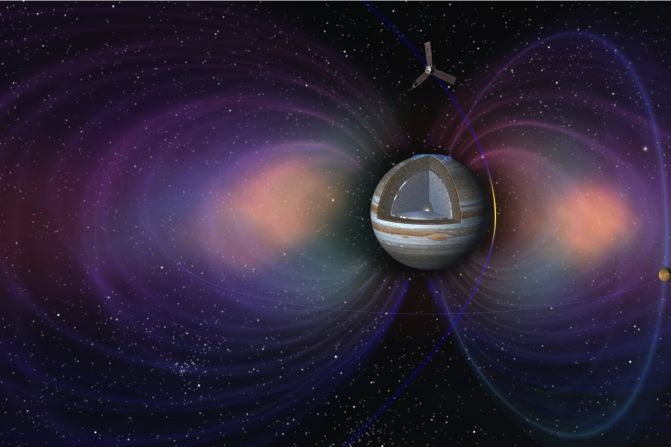

Based on its latest observations, Juno’s data about Jupiter’s gravity suggests that the planet doesn’t have a small, dense core as expected. Instead, there’s a diluted core, the researchers said. At first, they couldn’t understand why.

“Instead of a small compact core as we previously assumed, Jupiter’s core is ‘fuzzy,’ ” said Ravit Helled,study co-author, Juno mission team member and professor at the University of Zürich. “This means that the core is likely not made of only rocks and ices but is also mixed with hydrogen and helium, and there is a gradual transition as opposed to a sharp boundary between the core and the envelope.”

But what could disrupt the core? It would require something that could stir up the core. A giant impact seemed likely.

The international team of researchers used simulations of model collisions between the still-forming Jupiter with baby planets. Their results showed that a head-on collision between Jupiter and a young planet 10 times the mass of Earth would have enough impact to shatter the core. This would dilute it by allowing heavy metals to mix inside it.

“Because it’s dense, and it comes in with a lot of energy, the impactor would be like a bullet that goes through the atmosphere and hits the core head-on,” said Andrea Isella, study co-author and Rice University astronomer. “Before impact, you have a very dense core, surrounded by atmosphere. The head-on impact spreads things out, diluting the core.”

The study results were published this week in the journal Nature.

The researchers also wanted to know if the diluted core persisted over billions of years, or whether it evolved that way over time.

“We are talking about very different timescales,” said Simon Müller, study co-author and University of Zürich doctoral student who ran the simulations of Jupiter’s evolution. “Giant impacts occurred early in the history of the solar system and lasted for a short time, while the evolution is a long process up to today, 4.5 billions of years after Jupiter’s formation.”

Their calculations showed that the diluted core persisted, which has implications for more than just Jupiter.

“That makes the case for the giant impact much stronger,” Helled said. “It seems that such violent impacts were very common in the young solar system and interestingly, they played an important role in shaping the planetary characteristics – not only for Jupiter, as we suggest in this paper, but also for other planets, to explain the Earth’s moon, the high metal-to-rock fraction in Mercury, and Uranus’ tilt.”