Thousands of years ago, animals and the predators who tried to attack them became trapped in the La Brea Tar Pits, providing a treasure trove of fossils for research. Now, a detailed study of the predators found trapped in the tar is shedding light on why some are still found on Earth today but others went extinct.

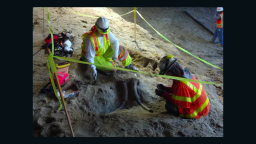

Today, visitors to Los Angeles can visit the tar pits to learn about the fossils discovered there. Excavations have been ongoing for more than a hundred years at the site. All of the predators found trapped in the tar alongside their potential prey creates an intriguing portrait of the Ice Age animals that are now extinct.

Vanderbilt University paleontologist Larisa DeSantis grew up visiting the fossil site in Hancock Park. Over the last decade, DeSantis used a dentistry approach to study the teeth of now-extinct predators like saber-toothed cats, dire wolves and American lions. She applied the same approach to the teeth recovered from the pits that belonged to ancient ancestors of gray wolves, coyotes and cougars.

DeSantis took molds of the different teeth and shaved off small enamel samples to analyze. Isotopes within the enamel stored information about their diet and wear patterns on the teeth showed if the predators were only eating meat or picking it off of bones.

The study published Monday in the journal Current Biology.

The predators were attracted to the pits because horses, bison and camels would become stuck in the tar. When they tried to reach the trapped prey, the predators themselves would also become mired in the tar.

La Brea also serves as a time capsule for climate change because the tar record encapsulates glacial periods and those in between from 2.6 million years ago to 10,000 years ago.

Previously, researchers believed that some of the predators went extinct due to competition for prey.

But DeSantis’ dentistry analysis showed that similar to today’s cats and dogs, the predators had different methods of going after their prey.

“Isotopes from the bones previously suggested that the diets of saber-toothed cats and dire wolves overlapped completely, but the isotopes from their teeth give a very different picture,” DeSantis said in a statement. “The cats, including saber-toothed cats, American lions and cougars, hunted prey that preferred forests, while it was the dire wolves that seemed to specialize on open-country feeders like bison and horses. While there may have been some overlap in what the dominant predators fed on, cats and dogs largely hunted differently from one another.”

Multiple factors likely contributed to the extinction of American lions, saber-toothed cats and dire wolves, including climate change, humans arriving in the same environment or a combination of both factors. Another continuing study is trying to refine the causes.

Coyotes, cougars and gray wolves were better able to adapt their diets by hunting small mammals or scavenge from carcasses when large prey disappeared.

“The other exciting thing about this research is we can actually look at the consequences of this extinction,” DeSantis said. “The animals around today that we think of as apex predators in North America – cougars and wolves – were measly during the Pleistocene. So when the big predators went extinct, as did the large prey, these smaller animals were able to take advantage of that extinction and become dominant apex-predators.”