He arrived at odd hours in the night, bursting through our front door with a massive duffel bag slung on his side and a big grin.

We’d jump with joy on his broad shoulders, inhaling the scent of Old Spice cologne and Pall Mall cigarettes. He then would steer us upstairs where he’d pull dragon statuettes from Vietnam and other exotic trinkets from his bag.

But the highlight of our ritual came when my younger brother or I would pull a wad of cash from his pocket, throw it on his bed and ask if the big bills were real.

“You can count it,” he’d say. “Spread it out.”

That childhood memory and others came to mind this week when President Trump engaged in another conservative ritual – bashing Baltimore. In a series of tweets, Trump described Baltimore as “the Worst in the USA,” and a “filthy place” where “no human being would want to live.”

I’m one of those black people who grew up in the “disgusting” community in West Baltimore that Trump described. So did my father – the man returning home with the duffel bag. His life as a black man illustrates how easy it is for the left and right to miss why the city’s black community in Baltimore has struggled so much.

There are hard truths about Baltimore that both sides ignore because they’re too inconvenient. You can’t fit them into a sound bite, and they don’t fit pre-existing narratives because much of what’s going on in Baltimore’s black community is happening in poor white communities across America as well.

Street violence, protests and lurid scenes from shows like HBO’s “The Wire” have come to define Baltimore. But a series of decisions, made outside of the spotlight in the city, have been as devastating to the city’s black community as a riot.

What the right won’t say about Baltimore

Almost every conservative critique I’ve read about Baltimore makes the same points: The homicide rate is out of control, taxes are too high and left-wing policies are killing the city.

They also toss in sermonettes on personal behavior, about families breaking down and the “pathological” behavior of young black men.

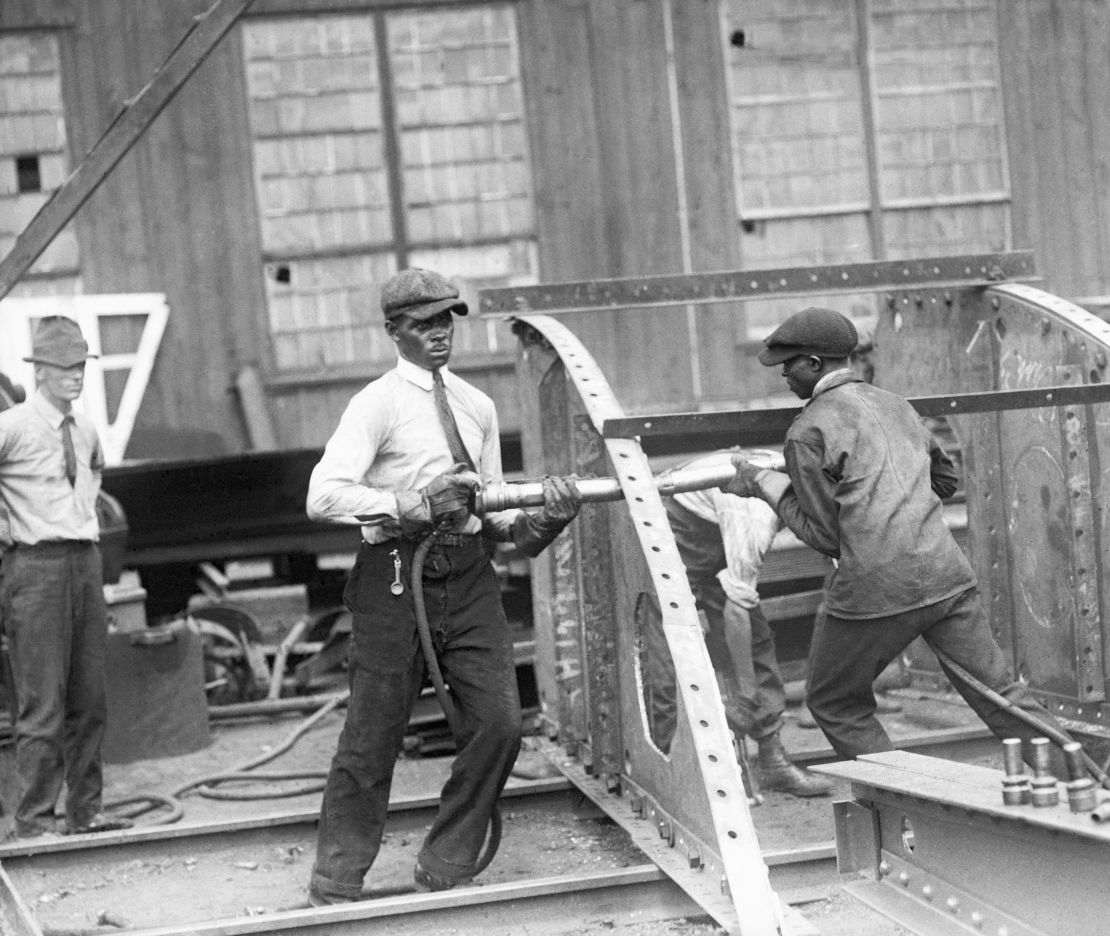

Here’s what they hardly mention – jobs. The blue-collar jobs that once formed the backbone of the black community in Baltimore have evaporated. So has the stability they provided to the community.

A decent-paying job is the best anti-poverty and anti-drug program you can offer. People delay gratification and plan for the future. But only if they feel like they have a future.

One of the reasons my father had that wad in his pocket is because he had a well-paying job, with union benefits, as a merchant marine. He purchased two homes, helped put three of his children through college and saw much of the world even though he only had a high school education.

The community I grew up in during the 1970s and ’80s was full of men and women like my father. Many of them had blue-collar jobs at places like the Bethlehem Steel plant or the Domino Sugar plant in the city’s inner harbor.

They proudly purchased big Chevy Impalas, kept their homes in impeccable condition and had crab cookouts in their backyards.

My neighborhood in West Baltimore is now an economic wasteland. Those stable, career jobs have now been replaced with minimum-wage service jobs and temp work.

You don’t have to stay in West Baltimore, though, to see what happens to communities when big companies pull out and plants close down. It’s happened throughout white America, too.

You hear about the same effects: “social collapse,” drug use, crime, the disintegration of family.

What you don’t hear, though, are lectures about personal responsibility. The community’s problems are often depicted as a public health crisis or one shaped by economic forces beyond residents’ control.

There’s something else conservatives also fail to take into account when talking about Baltimore: The impact of white flight.

The ‘white noose’ that strangles the city

Mention Baltimore’s black community and you cue images of boarded-up row houses, uncollected trash piles on the street and smoke curling over the skyline from the 2015 riots after Freddie Gray’s death.

What you won’t see, though, are pictures of caravans of white people fleeing Baltimore because the schools were desegregated in the 1960s and riots tore through the city after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Conservatives hardly ever talk about the impact of white flight on the city’s black community.

In 1950, Baltimore had a population of about 950,000. Today, it’s about 620,000. Fewer people means less money from property taxes and other fees. And less money means fewer resources to address needs, like failing schools or abandoned houses, for those left behind.

“It’s not just white flight; it was middle-class flight,” Kurt Schmoke, Baltimore’s former mayor, once told me. “All that tax base is gone.”

It was black flight, too. Many of the black families who could move out of the city did so the first chance they got. My family moved to suburban Baltimore when I was in college after my father collected a hefty payout from a shipping incident.

Some American cities coped with white flight by annexing neighboring counties to add more taxpayers. But Baltimore couldn’t do that because in 1948 voters in Maryland passed a provision making it virtually impossible for the city of Baltimore to annex neighboring counties. Some later described the more affluent counties surrounding Baltimore as a “white noose” strangling the city’s growth.

As its population fell, so did the city’s representation in the state legislature. State delegates don’t pay as much attention to Baltimore today. The city’s black community lost political clout.

A graphic reminder of this loss came in 2015, the year of the riots. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan canceled the Red Line, a light-rail system that was supposed to connect West Baltimore with the rest of the city. Hogan called the Red Line a “wasteful boondoggle.”

That decision didn’t grab the headlines like the riot did, but it was arguably just as destructive.

What the left won’t say about Baltimore

Even so, it would be simplistic to say all of Baltimore’s problems are due to racism or indifference.

The city’s black political leadership failed Baltimore as well.

When I call home to talk to my friends and siblings, I hear something I’ve never heard before. Many say they’re tired of black Democratic mayors and are ready to elect a white Republican.

Many of the black people I’ve met in West Baltimore say they feel as abandoned by upper-class black folks as they do by indifferent whites.

Much of that dismay springs from the sad record of Baltimore’s black mayors.

Catherine Pugh, the city’s most recent mayor, resigned earlier this year after allegations surfaced that she made nearly $700,000 selling her children’s book to entities that did business with the city. She apologized for doing something to “upset the people,” and returned $100,000.

Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, the previous mayor, was widely criticized for her handling of the 2015 riots and did not seek a second term.

Sheila Dixon, her predecessor, resigned after she was convicted of embezzlement after she stole gift cards meant for the poor.

An earlier Democratic mayor left a different type of legacy: a controversial approach to policing that saddled countless black men in Baltimore with police records for minor defenses.

Martin O’Malley, the city’s mayor from 1999 to 2007, came to power as drug violence escalated through the city’s black neighborhoods. He embraced a “zero tolerance” approach to policing with an emphasis on high arrest totals, even for minor offenses.

As a result, there are countless black men in Baltimore whose chances of getting a good job and raising a family have suffered because they have a criminal record.

There has also been a failure of imagination among some of our black youth.

This is treacherous terrain. I am loath to blame the problems in Baltimore on personal behavior. They’re too big and complex for that. But there is a psychological component to why the black community is struggling so much.

I see it in my family.

A sense of community, lost

I have known so many young men in my family and my neighborhood who seem like they’ve given up. They’re strung out on drugs, out of school and drifting day to day. They don’t seem to have any enduring relationships, romantic or otherwise. They blame all their problems on others – never on themselves.

Their behavior goes to a question I’ve asked myself for years: Why are they filled with so much bitterness and defeatism? And why did my father and my older relatives have so much more hope even though they seem to have experienced more hardships?

My father should have been bitter. He and my older relatives routinely experienced raw, in-your-face racism. My father was physically attacked by white men in public on several occasions because they thought he was acting too uppity.

“I’ve been called n***** so much that I thought it was my middle name,” he once told me.

Yet he was the most optimistic man I ever knew. He never complained about racism or blamed others for his difficulties. I see none of his strength in many of the young men I now know in West Baltimore. I wonder if any of it is even in me.

What did he have that so many of them don’t have now?

Two answers come to mind.

My father had a sense of community. He and all my uncles and aunts belonged to unions, the National Guard, Greek fraternities, secret societies, churches. It gave them strength and support.

That’s evaporated in much of West Baltimore. The younger men I know don’t belong to any groups. They’re isolated. When I returned to my old neighborhood during the riots in 2015, one of my old neighbors told me nobody sat on front porches and talked to anyone anymore.

“I could be mutilated and lying on the street,” he said, “and nobody would help or call the police.”

And my father and his generation had something else: They felt like life was going to get better, no matter how tough things got.

With the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, he thought his time was finally going to come.

“I wanted to make sure I got a fair deal at the bargain, whatever I did,” he once told me.

A thought that’s scarier than a riot

I don’t think many young blacks in Baltimore now feel their time will ever come. The cancelation of the light-rail line was a symbol of something deeper – they are now physically and psychologically cut off from the rest of the world.

White and black political leaders have let them down. Middle class blacks have abandoned them for better neighborhoods. And the President talks about them like they’re subhuman.

My father lived long enough to see how West Baltimore had crumbled. He lived long enough to see Trump elected. In fact, he liked to tease me that he did his part: He voted for Trump. When I would ask him why he’d rebuff me.

“I can’t tell you that,” he’d say. “That’s personal now.”

He died last year, just weeks before his 92nd birthday. I miss him, but I also miss those little rituals we shared, and the pride he took in carrying a thick wad of bills in his dungarees.

My father felt like he got a “fair deal at the bargain.” But here’s a thought that’s scarier to me than a riot and more depressing than a President who tweets about rodents infesting my neighborhood.

I wonder if the young people in my family, and my neighborhood, will ever feel the optimism my father felt.

I wonder if most people in West Baltimore, and even many Americans, will ever feel that way about this country again.