Anheuser-Busch InBev built a sprawling beer empire by borrowing heavily to acquire rival SABMiller.

That monster deal allowed the king of beer to push into fast-growing markets in Africa and away from the United States, where drinkers are switching to craft beer from mass-market beers like Bud Light and Budweiser. But the SABMiller takeover also left AB InBev with more than $100 billion in debt.

Under pressure from Wall Street and credit ratings firms, AB InBev (BUD) has been forced to attack that mountain of debt by raising cash so it can repair the balance sheet. AB InBev (BUD) has cut its dividend in half, unloaded its Australian business for $11.3 billion and explored an IPO for its Asia-Pacific division.

“Everyone was expecting them to deleverage faster,” said Laurent Grandet, beverage and food lead analyst at Guggenheim Securities.

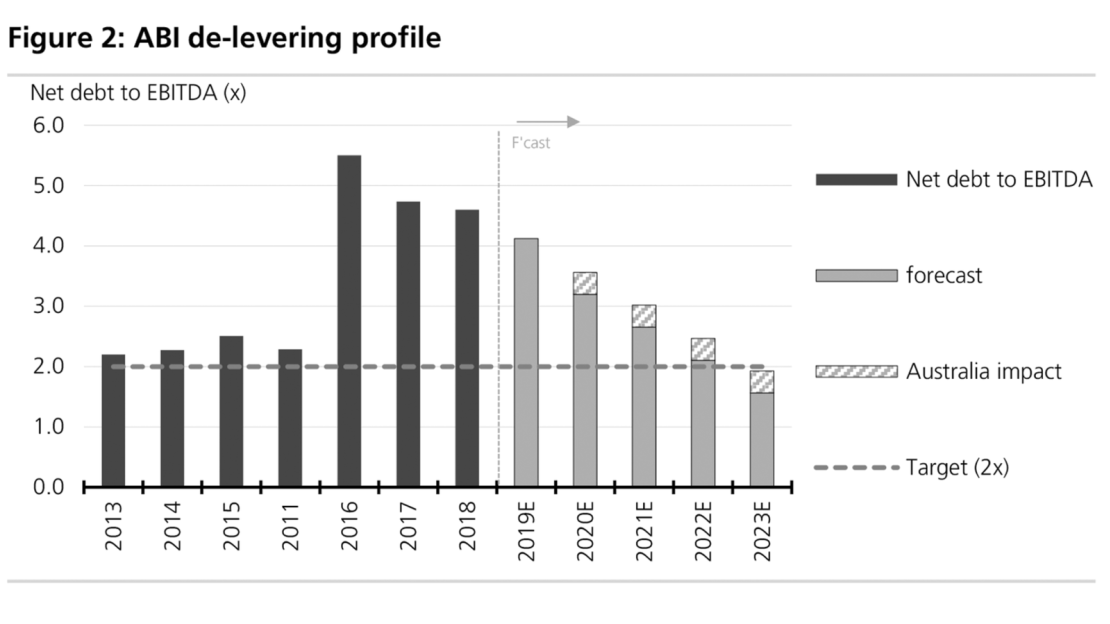

AB InBev’s leverage — its debt to cash ratio — spiked after the $108 billion SABMiller deal closed in late 2016. By the end of that year, the company’s net debt rose to about 5.5 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or EBITDA. That’s more than double the company’s pre-deal leverage and well above its target of two times EBITDA.

That amount of borrowing worried credit ratings firms. Companies with too much leverage face higher borrowing costs and can run into financial trouble in a downturn or if credit markets freeze up. Even in good times, strained balance sheets leave companies with little money to invest in the future.

“It’s at the bottom of the investment grade scale because of the high pile of debt that has so far not materially diminished since they concluded the acquisition of SABMiller,” said Giulio Lombardi, an analyst at Fitch Ratings.

Craft beer problem

AB InBev’s debt paydown was slowed in part by continuing problems in the United States.

“Their market share has been constantly eroding for the past 10 years in the United States,” said Lombardi.

During the first quarter, AB InBev’s core, light and value brands lost another percentage point of market share. The company said its mainstream segment “remains under pressure as consumers move to higher-price tiers.”

“The hot spot for the past decade has been super-premium beer because the economy has been strong and consumers have been trading up,” said Linda Montag, senior vice president at Moody’s Investors Service.

AB InBev was also hurt by economic trouble. The SABMiller deal increased the company’s exposure to fast-growing, but volatile emerging markets. Although that makes sense given the softness in the United States and mature markets like Western Europe, it backfired at first because Brazil and South Africa tumbled into recession.

Dividend cut not enough

Those problems, coupled with the mountain of debt, forced AB InBev to slash its dividend by 50% in October to save about $4 billion in cash a year.

Fitch’s Lombardi questioned why AB InBev didn’t make that painful decision sooner.

“Had they started paying down debt by reducing dividends early on they wouldn’t have this pile of debt,” he said.

In any case, Lombardi said the dividend cut “was not sufficient” to reduce leverage to a level that would avoid a credit rating downgrade.

That’s why AB InBev was hoping to raise as much as $9.8 billion by listing a piece of its Asia-Pacific business in Hong Kong. It would have been the largest IPO of the year. At the high end of the range, the deal would have also been the biggest food and beverage IPO on record, according to Dealogic.

However, AB InBev suddenly pulled the IPO earlier this month, citing “several factors including prevailing market conditions.” Given that the decision to yank the IPO occurred during a bullish moment in global markets — US stocks had just hit record highs — the move suggests AB InBev struggled to receive an attractive price for the assets.

Asia IPO could still happen

AB InBev quickly moved to Plan B: unloading the slower-growing portion of the Asia-Pacific division. Last week, the company agreed to sell its Australian unit to Japanese beer giant Asahi.

In a nod to market fears about its debt load, AB InBev promised to use “substantially all” of the proceeds to pay down debt and reiterated its goal of slashing debt-to-EBITDA ratio below 4 by the end of 2020.

AB InBev also kept the door open to an IPO of the remaining Asia-Pacific business, “provided that it can be completed at the right valuation.”

The strategy is a bit of addition by subtraction. The Asia-Pacific business may look more attractive now because Australia is growing much slower than the remaining Asian markets such as China.

“We believe the transaction makes sense given ABI’s high leverage and our view that Australia is not a ‘strategic’ asset,” UBS analyst Nik Oliver wrote to clients last week.

What if there’s a recession?

Analysts are optimistic that after its slow start, AB InBev is finally on the path to cleaning up its balance sheet.

Although the king of beer has a ton of debt, it’s also generating vast amounts of cash and has many ways to raise more of it.

“It’s not a situation where we have concerns they may not be able to repay the debt,” said Fitch’s Lombardi.

Of course, time is of the essence.

AB InBev’s deleveraging could be complicated if the economic and financial market backdrop deteriorates. A recession would make it more difficult for highly-leveraged companies to refinance debt and sell down assets.

The silver lining is that a recession might not dent beer volumes.

“The nice thing about the alcoholic beverage industry is that people tend to drink in good times — and in bad,” said Montag.