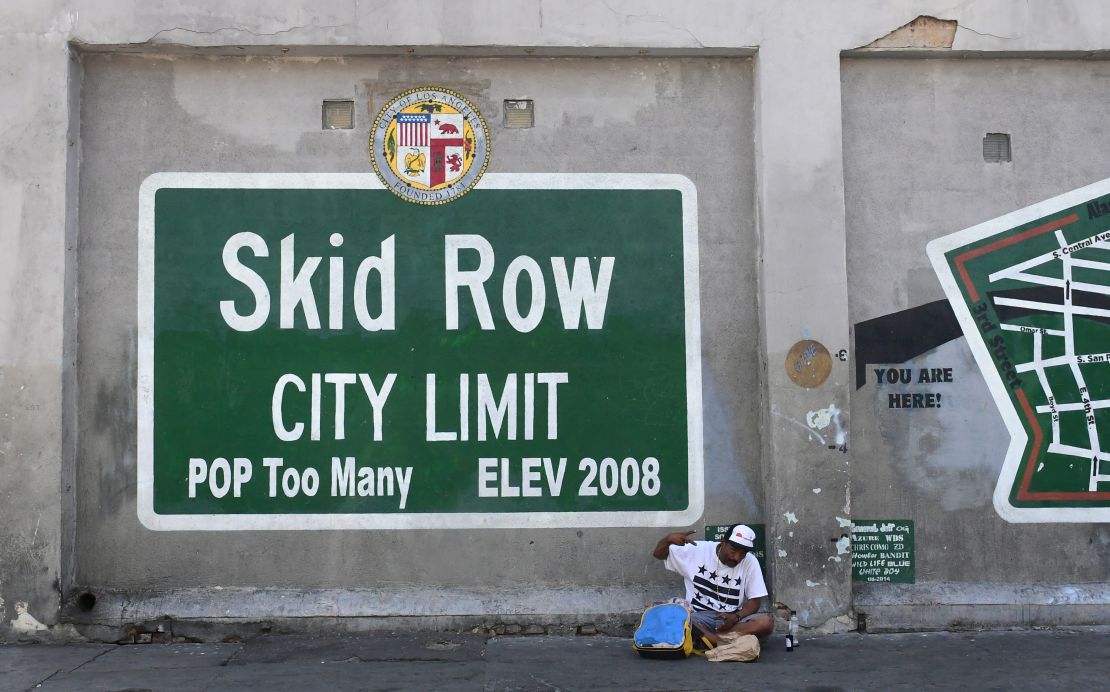

In Los Angeles’ Skid Row, tents line entire city blocks. These makeshift shelters for the city’s homeless are now an almost permanent fixture of the city’s landscape, with barbecue grills and clusters of bikes standing alongside them.

Some residents have tethered their tents to nearby fences and industrial buildings. Others run long power cords from their tents to nearby light poles to tap into the city’s power grid. A few Skid Row pet owners have created small dog yards next to their tents under tarps to block out the sun and makeshift fencing. On a recent evening in this industrial part of LA’s downtown, a young woman was washing her hair and her tank top in the jet of water gushing from a fire hydrant into the street.

As Los Angeles city and county officials struggle to shelter and build housing for nearly 60,000 people who are living on the streets, they are facing resistance – not just to new structures in neighborhoods where residents fear more crime and blight, but also from some within the homeless community, who insist they would rather continue living independently on the streets in their tents.

While the homeless crisis is perhaps most visible in California, it is gripping so many other cities, including Washington, that many of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates are beginning to face questions from voters about their plans. In 2018, about half of all Americans experiencing homelessness lived in one of five states – California (24%), New York (17%), Florida (6%), Texas (5%) or Washington state (4%), according to the 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, presented to Congress in December.

In dozens of interviews with unsheltered people in LA over the past year, many told CNN they won’t apply for housing because they are afraid of the police, or unable to access the right documents to apply for ID, or sometimes simply wary of losing their independence if they are forced to live under rules that might be imposed if they moved into subsidized housing facilities.

IN PICTURES: L.A.’s homelessness crisis

Tents are now all over LA County. But the so-called “shelter-resistant” population is most evident in Skid Row, the portion of downtown where many of the city’s homeless shelters, temporary housing and homeless services have traditionally been concentrated.

At the root of this tremendously complex problem is the fact that many within LA’s unsheltered population are grappling with substance abuse addictions and untreated mental illness. Another major factor is that a series of lawsuits against the city – aimed at preserving the rights of homeless people to protect their property – has created a semipermanent tent culture in some sectors of LA.

Under city policy, tent-dwellers are required to take down their tents during daylight hours to clear the streets for pedestrians and business owners. But because of the lawsuits, that policy is not being uniformly enforced. In some areas it does not appear to be enforced at all.

The lawsuits and court injunctions against the city have had other unintended consequences. Because of the proliferation of tents, police say, it is much harder to identify and halt drug dealing and human trafficking. The legal battles have also complicated the city’s ability to clear trash-strewn streets, because it is not easy to identify what bedding or clothing might belong to an unsheltered person living nearby.

Homeless women most vulnerable

The way in which tent culture feeds resistance to housing is one of the greatest frustrations for Los Angeles Police Officer Deon Joseph, who has worked in Skid Row for more than two decades both as a homeless advocate and enforcer.

During several nighttime patrols through Skid Row, he reeled off countless stories of unsheltered women who he has tried to get into the pipeline for housing, in part because they are among the most vulnerable to sexual assault, domestic violence and even demands for money from gang members who try to charge rent on certain blocks.

Several times a year, Joseph holds what he calls “Ladies Night” for the women of Skid Row – a workshop where he brings in advocates to teach self-defense, how to report assault and rape, and legal rights.

He often cites the example of a 70-year-old woman named Lena living in Skid Row who he got to know well but who was resistant to housing: “I tried to house her, tried to house her, tried to house her,” Joseph said, “and then one day I came back and someone found her dead in a pile of garbage. A human being found in garbage.”

Joseph notes that scores of well-meaning volunteers and church groups show up on Skid Row each month to try to help the population by providing food, clothing and even new tents. But in Joseph’s view, that assistance often perpetuates the cycle of people living on the street.

“The shelters and the missions here, they give food and clothes to draw people in to get the services to that help people get on their feet – like drug programs, alcohol programs, domestic violence program, job programs,” Joseph said. “But many of the folks from here won’t use them, because they’re getting their needs met on the streets of Skid Row.”

Rising homeless rate

As a result of several ballot measures approved by LA voters in the past few years, the city and the county spent hundreds of millions of dollars last year to address the homeless crisis. But the number of people living without shelter still went up 12% in the county and 16% in the city. Homelessness among youth and children rose 24% over the previous year, according to the 2019 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Results.

Of the nearly 60,000 people who are homeless in LA County, 19% told officials they came to LA County from out of state, 15% said they arrived from another part of California and 1.2% said they came from outside the United States.

While the homeless count in Los Angeles was shocking, the rise in homelessness in neighboring counties was equally bracing. Homelessness was up 43% in Orange County over the previous year, 28% in Ventura County and 50% in Kern County.

When questioned about why they had fallen into homelessness, 53% of those who said they were homeless for the first time in LA County cited “economic hardship”– with the lack of affordable housing serving as a major driver for many.

The staggering homeless count rose despite the fact that LA’s coordinated city-county homeless crisis response system helped 21,631 people move into permanent housing last year.

Another 31,500 people have been assessed by case managers and are waiting for housing or rental subsidies, according to city and county homeless officials. The county has opened eight new mental health urgent care centers and a sobering center to expand its outreach.

Housing for the homeless

While Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti has confronted serious opposition in some neighborhoods even for his initial goal of placing 15 new shelters in City Council districts across the city, residents of some parts of Los Angeles County have been more receptive to housing for the homeless.

One example is the former Tiki Motel in LA County, a notorious site of neighborhood crime and blight that appeared in the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie “The Terminator.”

Al Nunez, who grew up in East Los Angeles and was homeless for three years after his mother died of lung cancer, is one of the residents who now live at the converted Tiki Apartments.

Nunez was paralyzed by a gunshot wound to the spine 16 years ago. He often got sick during the time he was homeless, and would go days, he said, sleeping in his wheelchair.

“They would call me ‘the statue,’ ” he recalled in an interview. “I was just alone because I was ashamed and embarrassed. Especially, where I was at – it was my neighborhood where I grew up.”

Former friends and acquaintances would often pass him on the street: “They wouldn’t even acknowledge me or say anything to me. But I understand, it’s because it’s a stigma like – ‘You’re homeless’ – It’s like I wasn’t the same person.”

“All I could think about is that I was going to either die from getting sick – from being in my wheelchair – or to the point where I wanted to take my own life because it was just a lot of suffering,” he said. “The only time I would go lay on a bed was when I would end up in the hospital. But … once I was stable, it was like, ‘You’ve got to go back on the street and fend for yourself.’ “

At another housing development called Mosaic Gardens at Willowbrook, in an unincorporated area of LA County, formerly homeless residents or those who were housed here because they were on the brink of homelessness have a playground, a computer lab and financial literacy programs, as well as access to services to help treat substance abuse or mental illness.

Suny Lay Chang, the chief operating officer of LINC Housing Corp., which built the project, notes that they involved the community in the design, from the paint colors to the city-in-the-country feel that they tried to create with a community garden and kitchen.

“We have groups come in to lead cooking classes and demonstration classes to help people learn how to eat healthy, cook healthy. We’ll use some of the vegetables from the community garden to do that,” Chang said. “It’s part of treating the whole individual.”

The project got off the ground, in part, because the community got behind it. One of the community leaders involved was Michael Torrence, a minister at nearby Fellowship Baptist Church who also directs a substance abuse prevention program for youth and families that is part of Volunteers of America of Greater Los Angeles.

Torrence said residents from the Willowbrook community were there “from the planning to the first shovel to the cutting of the ribbons.”

“We feel a great sense of ownership,” he said during an interview in the community kitchen of Mosaic Gardens at Willowbrook. “I’m not a resident here, but as far as I’m concerned this is my place too.”

When asked about the resistance in other parts of Los Angeles to building homeless housing units and shelters, Torrence said he would argue that those neighborhoods will be safer if currently unsheltered people have ready access to wraparound services for substance abuse and mental health issues.

“Not in my backyard is only because you have a backyard right now,” Torrence said. “We have to recognize the fact that these are people.”

“If we address this, and provide housing and assistance and support – then you can get past the whole notion of this is the other – and begin to see them as my neighbor,” he said.

“So, your backyard? If they’re invested in it, they will take care of the backyard.”

A national political issue

When Los Angeles County released its shocking homeless count this month, Sen. Kamala Harris tweeted that housing is a “human right,” noting that her proposed LIFT Act – to give lower-income working families a tax credit of up to $6,000 a year – as well as her “Rent Relief Act” are intended to address the crisis.

The California Democrat and presidential candidate, addressing the Poor People’s Campaign Forum in Washington on Monday, also introduced a new line in her campaign speech, saying, “What we learn in that parable is that neighbor is that person you are walking by who is homeless on the street.”

Julian Castro recently toured storm tunnels beneath the Hard Rock Café in Las Vegas where hundreds of homeless individuals have sought shelter – and on Monday he outlined his plan to “end chronic homelessness by the end of 2028.”

“It wasn’t lost on me or anyone else there that underneath hotels that are worth hundreds of millions of dollars,” Castro said, “you have people who are living in deep poverty, sleeping not even in the street but in a drainage tunnel.”

California voters approached both Joe Biden and Beto O’Rourke citing homelessness as a top concern during their respective visits to the Golden State. A voter in San Diego – a city that erected enormous tent shelters last year to temporarily house hundreds of people – told O’Rourke she was worried about the number of veterans living on the streets. The former Texas congressman noted that some of the homeless veterans he has spoken to in his home state had to wait so long for mental health treatment that they sought drugs on the street to treat their symptoms.

“If you cannot see a doctor and be well enough – then there’s a more likely chance that you’re going to be homeless in the first place,” O’Rourke told the voter during his San Diego town hall in late April. “So starting with health care for everybody – without exception, including mental health care – is so fundamental to being able to get this done. And in California, perhaps especially, where housing prices are going through the roof, we’ve got to make sure that we are creating enough housing units for the demand that is here.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont routinely highlights the growing number of homeless people nationwide as he rails against the fact that 40 million people are living in poverty while the “very rich” are “getting richer.” “Tonight some 500,000 Americans, including many veterans, will be sleeping out on the streets,” Sanders said during a speech earlier this month at George Washington University.