NASA has touted its bold plan to return American astronauts to the moon by 2024 for months. Now we’re starting to get an idea of how much it will cost.

The space agency will need an estimated $20 billion to $30 billion over the next five years for its moon project, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told CNN Business on Thursday. That would mean adding another $4 billion to $6 billion per year, on average, to the agency’s budget, which is already expected to be about $20 billion annually.

Bridenstine’s remarks are the first time that NASA has shared a total cost estimate for its moon program, which is called Artemis (after the Greek goddess of the moon) and could send people to the lunar surface for the first time in half a century. NASA wants that mission to include two astronauts: A man and the first-ever woman to walk on the moon.

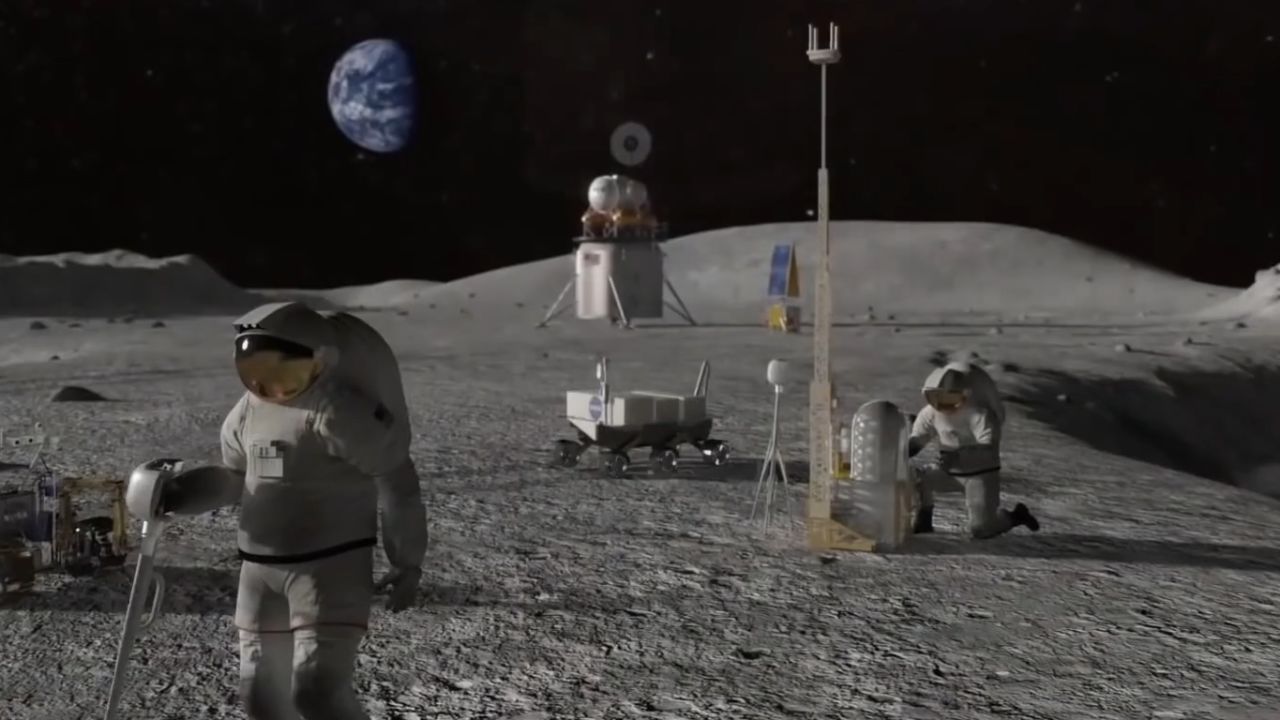

The overall goal of the Artemis program is to establish a “sustainable” presence on the moon, paving the way for astronauts to return to the surface again and again. Learning to live and work on another world, Bridenstine said, will prepare them for NASA’s long-term mission: to put people on Mars for the first time in human history.

The $20 to $30 billion cost estimate is less expensive than some had predicted — though they’re not necessarily the final figures. Bridenstine acknowledged that spaceflight can be dangerous and unpredictable, so it’s practically impossible to settle on an accurate price tag.

“We’re negotiating within the administration,” he said. “We’re talking to [the federal Office of Management and Budget]; we’re talking to the National Space Council.” (The National Space Council is a recently revived policy development group headed by Vice President Mike Pence.)

“Once we come to a determination within the administration,” Bridenstine said, “we will of course take that over to the Hill and make sure that our members of Congress are interested and willing to support that effort.”

Will NASA get its money?

Winning over lawmakers, however, will likely be the most difficult part.

Pence announced in March that the Trump administration wanted to speed up NASA’s moon ambitions, and launch the first crewed mission in 2024 instead of 2028, the agency’s earlier timeline. That’s just five years away. And all the hardware that NASA needs is either delayed, way over budget or doesn’t yet exist.

So far, NASA has formally requested only an additional $1.6 billion for Artemis, which Bridenstine has described as a small “down payment” for the overall program.

Meanwhile, members of Congress have been after the administration for a total cost estimate and a detailed plan on how it will spend the money. Bridenstine will also have to win over Democrats who are already skeptical.

Critics also point out that NASA has poured billions of dollars into deep-space programs over the past 15 years, though humans still have not been back to the lunar surface since the final Apollo mission in 1972.

The Apollo program also happened in a very different political environment. It was during a bitter Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, and the United States was in a mad dash to beat its enemy to the lunar surface. All told, the United States spent about $25 billion on the Apollo program, or nearly $150 billion in today’s dollars.

Some fear that NASA will end up diverting funds from its other programs, which include robotic exploration missions, Earth science and climate studies and other important scientific research.

“I will tell you my goal — and I’ve been very clear about this — is to make sure that we’re not cannibalizing parts of NASA to fund the Artemis program,” Bridenstine said.

And, he said he’s confident that NASA will convince Congress to get on board: “I think there is a strong desire. It’s bipartisan to explore, to learn, to understand the science and the history of our own solar system.”

Breaking down the budget

NASA and US taxpayers have already invested heavily in the rocket and spacecraft that will be used for the trip. But those projects have been routinely criticized. They’re years behind schedule and way over budget.

Space Launch System, or SLS, is the name of a gargantuan new rocket that promises to out-power any launch vehicle ever built and be capable of flinging people toward the moon or Mars.

SLS was once expected to cost about $9.7 billion and start flying in 2017. But NASA has already spent at least $12 billion, according to a recent Office of the Inspector General report, and it’s not expected to fly until next year at the earliest.

Similarly, Orion, the name of the spacecraft that will launch on top of SLS and carry astronauts out to the moon, is hundreds of millions of dollars over budget, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Other hardware NASA needs that doesn’t exist yet: A small space station that will orbit the moon and serve as an outpost for astronauts, called the Lunar Gateway, along with a lander that’s capable of taking people from the station down to the moon’s surface.

These are not cheap projects.

Still, NASA’s expenses have been a drop in the bucket compared to many other departments. The annual Defense Department budget, for example, has reached $1.3 trillion per year. Health and Human services gets about $90 billion per year. And Homeland Security annually receives about $50 billion.

What it means for business

NASA isn’t the only organization talking about going back to the moon. The United States has a booming commercial space industry, and SpaceX, the rainmaker of the industry, has its own plans to build a giant rocket and fly tourists around the moon.

And NASA is paying attention: A significant chunk of research and development for the Artemis program will come from the private sector. It’s part of NASA and Bridenstine’s plan to lower costs and make space an entrepreneur-friendly environment.

“We’re going back to the moon, but we’re doing it entirely different than we did in the 1960s,” Bridenstine told CNN Business. “The reason we need commercial operators is because they can drive innovation if they’re competing on cost and innovation.”

NASA has long worked with corporate contractors. Boeing, for example, helped build the Saturn V rocket that powered the Apollo program. And these days, Lockheed Martin and Boeing are primary contractors for Orion and SLS.

But NASA’s commercial partnerships are different: The space agency wants private-sector companies to design, test and build technologies and then compete for lucrative government contracts. Essentially, Bridenstine says, NASA will become just another customer for companies in the business of space travel.

The space agency has already made it clear it wants to turn to the private sector to take care of lunar landers. Three small companies that build robotic landers were awarded tens of millions of dollars from NASA to drop cargo off at the moon. And startups such as Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, which is building a crew-worthy lander called Blue Moon, are gunning for space agency contracts.