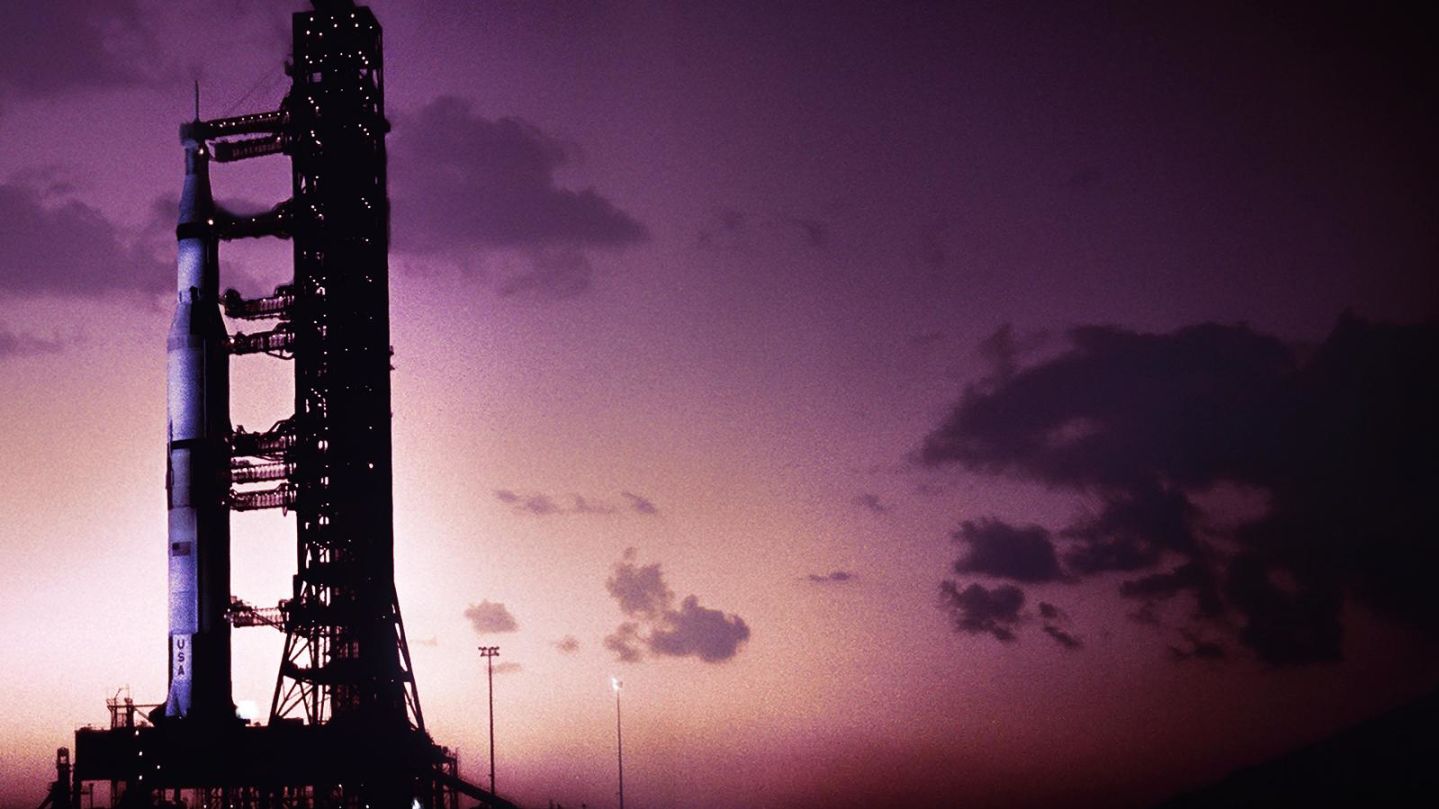

CNN Film ‘Apollo 11’ explores the exhilaration of humanity’s first landing on the moon through newly-discovered and restored archival footage. Watch the TV premiere of this documentary Sunday, June 23 at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

One of the best questions that astronaut Dr. Mae Jemison has ever received was from a 12-year-old girl: “How did being a dancer help you be an astronaut?”

Jemison, who became the first African American woman in space during her 1992 shuttle mission, was the child of two scientists. She looked up at the stars with wonder. She wanted to be a scientist, a dancer, an architect and a designer. Jemison took studio art classes, making ceramics, silk screenings and other forms of art. She didn’t know that she would become an astronaut; she thought maybe she could be those other things in space.

“At the core of them are creativity, because I wanted to help influence where the world went,” Jemison said. “I wanted to use my energy and my ideas to design new things, to explore the world around me. And we’re very physical beings, so dance is a way of physically exploring the world.”

Jemison explained to the girl that dancers must be disciplined, practicing and rehearsing constantly and paying attention to those around them while maintaining the choreography in their head. Dancing also requires the ability to take criticism and apply it.

Jemsion is an advocate for maintaining the arts in schools, in addition to science, technology, engineering and mathematics, a group of fields known as STEM.

“The sciences help us understand and convey ideas about the world as it’s experienced by everyone,” Jemison said. “And I think of the arts as helping us to convey understanding of the world as it’s experienced by the individual. Both of them are required for creativity. Both of them are required to move the world forward. It makes us full, rounded human beings. And it also keeps us interested.”

Diversity of all kinds is crucial to push the boundaries of space exploration; art is often lost in that part of the story. But for 50 years, art has also been helping tell the story of how humans are exploring space.

Artistic astronauts

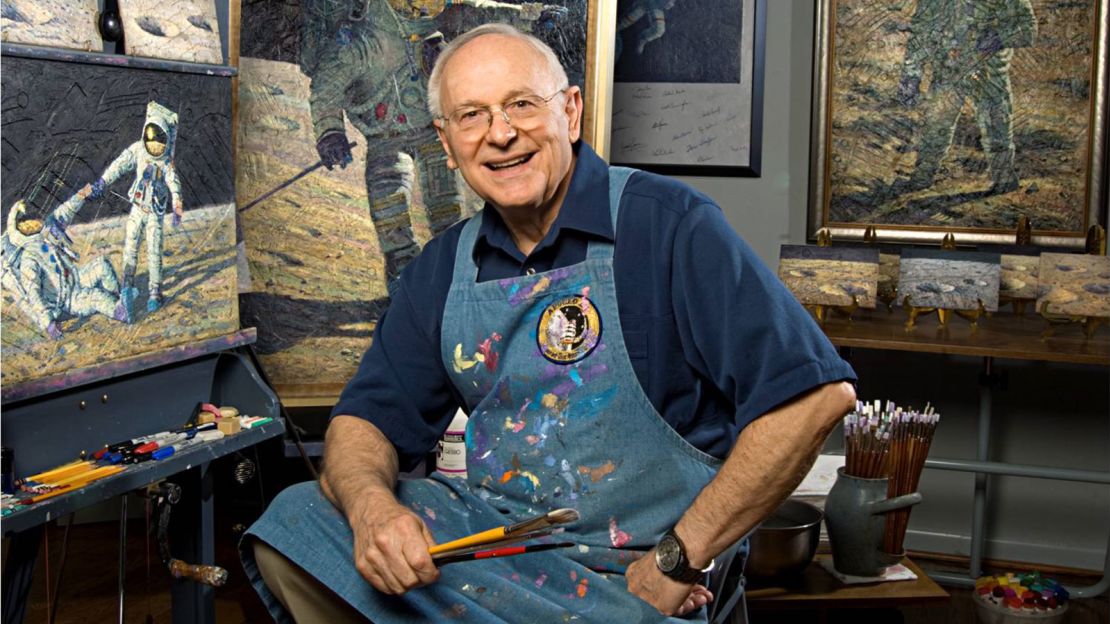

Alan Bean, the lunar module pilot for Apollo 12 and the fourth man to walk on the moon, had taken art classes before he became an astronaut. The artwork he created after returning to Earth tells the story of his mission, as well as the missions of other Apollo astronauts. When he resigned from NASA in 1981, he set out to share the truth and beauty of what they had seen.

His artwork has been exhibited at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

“Alan Bean and his astroartistry recreate the drama and excitement of man’s exploration of the moon as only could be chronicled by one who has been there,” astronaut Neil Armstrong said, according to Bean’s website.

Throughout his works, Bean used pieces of his spacesuit, the imprints of moon boots, marks from tools like a hammer and core tube bit he used on the lunar surface, and even small pieces of foil insulation and dust from the Apollo 12 landing site, known as the Ocean of Storms.

Bean, who died in 2018, was inspired by other explorer artists. “My paintings record the beginnings of a quest never to end, our journey out among the stars,” he wrote on his website.

Fellow astronaut John Glenn said, “he saw the same monochromatic world as the other astronauts, yet with an artist’s eye he also saw intrinsic beauty in the rocks and boulders and their textures and shapes.”

He was the first artist to land on the moon, but he wasn’t the only astronaut with a passionate connection to art.

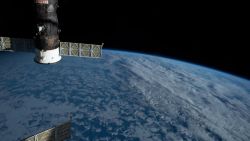

Astronaut Nicole Stott, who spent 104 days living and working in space during two missions became the first to paint with watercolors in space during her 2009 mission.

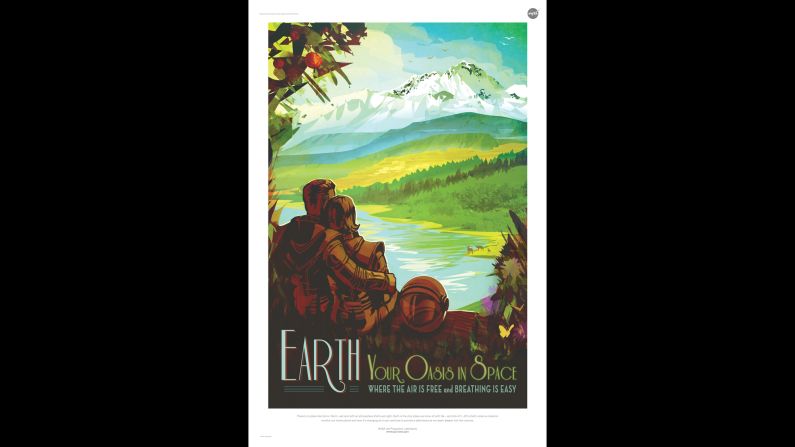

Stott shares her unique view of space and the Earth through her work, aiming to promote the importance of science and art as well as the desire to care for our planet. She said that every astronaut has that moment when they come back to Earth: What do I do next? She couldn’t stop thinking about painting in space.

“Being able to look out the window and see something and paint my interpretation of it seemed meaningful,” Stott recalled. “Maybe my artwork is a way to uniquely share my experience. It’s been a really wonderful way to connect with people about appreciating where we live on this single planet. We need to take care of it.”

Stott is also the founder of the Space for Art Foundation, a nonprofit that creates space-inspired art therapy programs, research and exhibits. The Spacesuit Art Project was one of the recent aims of her foundation, which continues the quest for awareness around childhood cancer.

The project completed three suits made of art created by children in hospitals: Hope, Courage and Unity. On September 16, 2016, the stark whiteness of the International Space Station became an art gallery when astronaut and cancer researcher Kate Rubins donned the Courage suit and called down to Earth to speak with some of the patients.

“The spaceflight experience I’ve had is going to allow me opportunities to participate in projects like this,” Stott said. “It’s the most meaningful thing I’ve ever supported.”

“It’s always nice to meet a kindred spirit,” Bean said when he met Stott, according to her website. “I’m delighted that Nicole is the first astronaut of the Space Shuttle/Space Station era to choose art as her next step in life. All of us that have been fortunate enough to fly in space find it difficult to describe the beauty of our universe in words alone. I am thankful that Nicole has chosen to help share these amazing sights we have all seen through her very beautiful artwork.”

A window to space

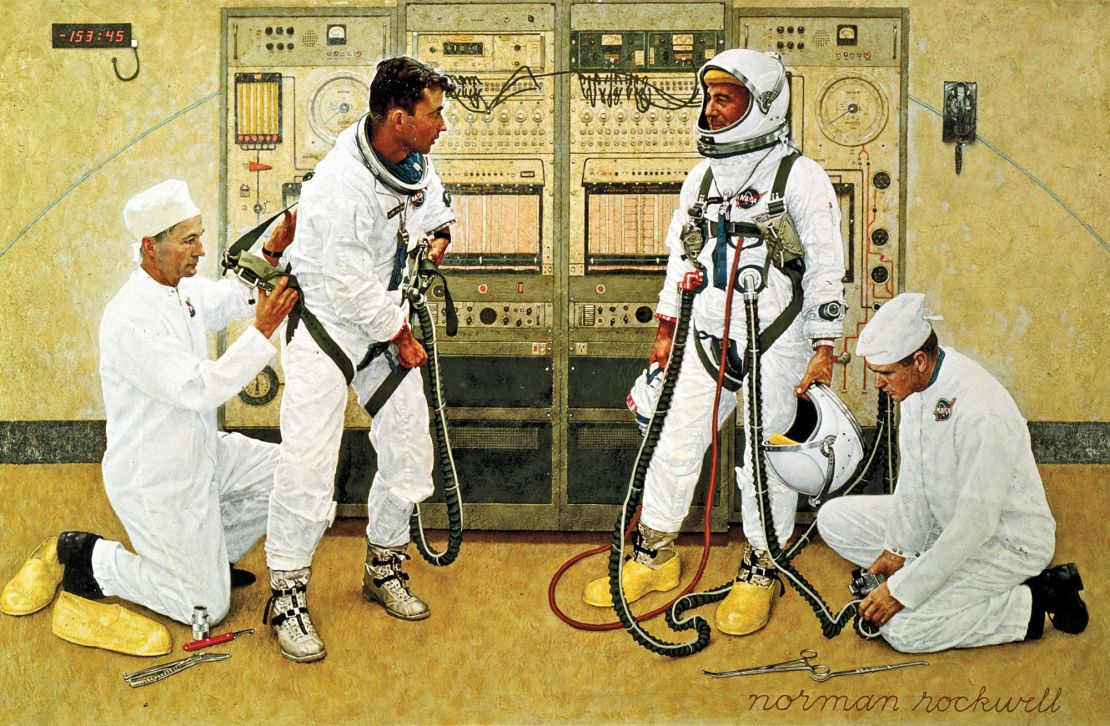

Art was a priority for NASA’s second administrator, Jim Webb. He established NASA’s art program in 1962 and allowed artists to start coming to the agency in 1963. He saw a need for art to capture the history that was being made and portray it for the American people. And the artists were given free rein.

The leading artists of the time were invited to capture history. Norman Rockwell’s famous painting of astronauts Gus Grissom and John Young originated during the early days of the program in 1965. NASA loaned a spacesuit to Rockwell so he could accurately capture the details.

“Art is part of what makes us human,” said Bill Barry, NASA’s chief historian. “It captures the feeling of what it means to explore, which is what discovery is all about.”

Much of the art from that program is at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

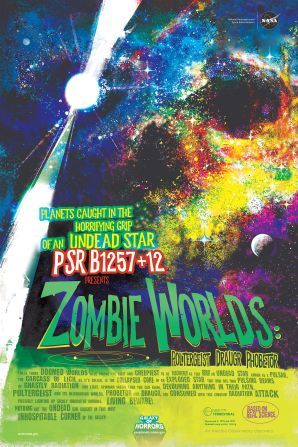

Separate from that program, art is still being produced out of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, through The Studio, and from artists Robert Hurt and Tim Pyle at the California Institute of Technology.

The Studio brings together artists and designers who work with scientists and engineers at NASA to inspire awe about the work and research being done at the agency.

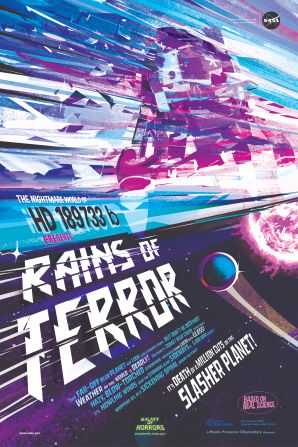

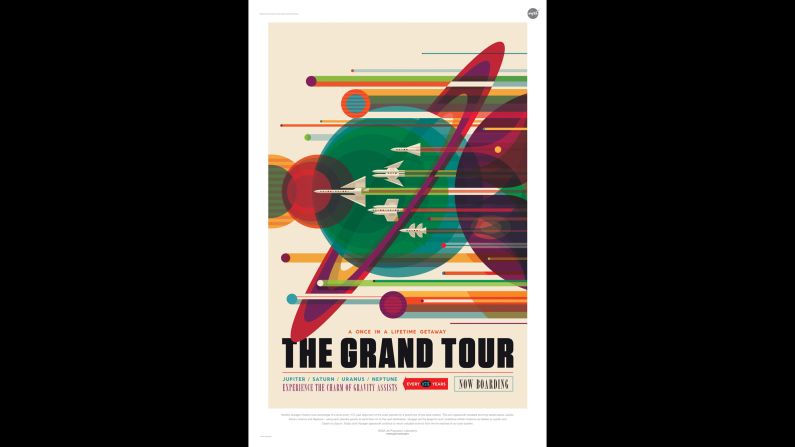

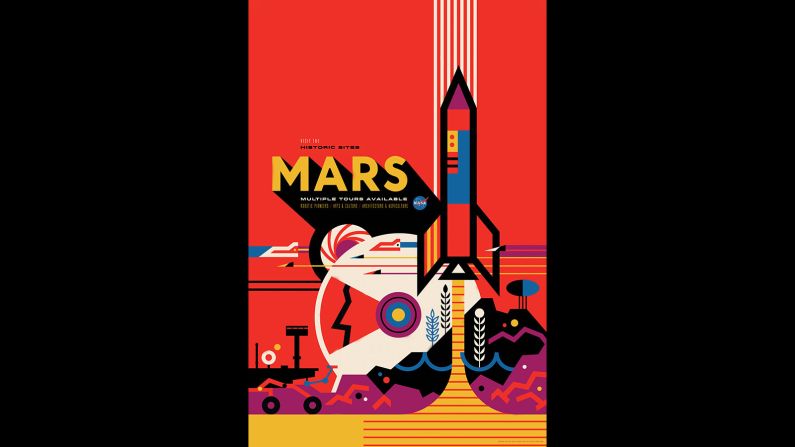

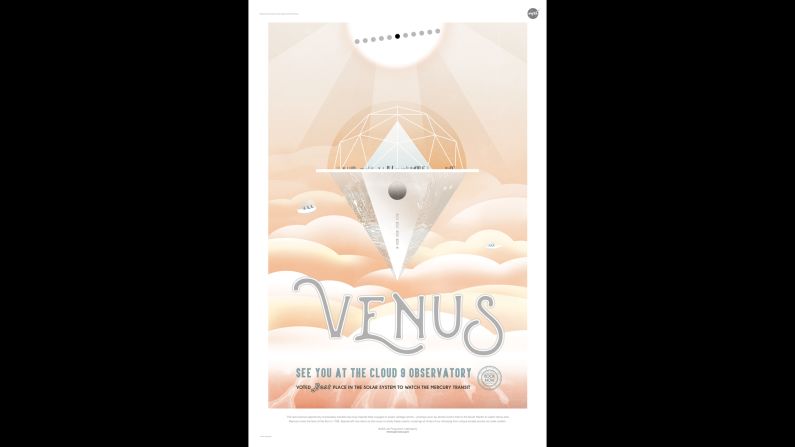

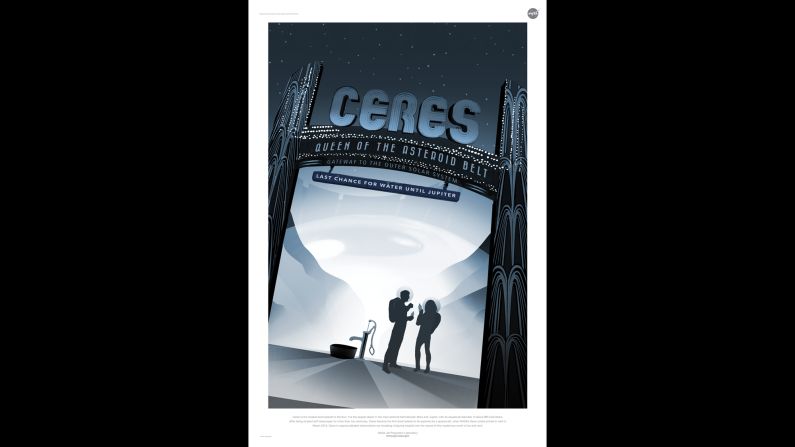

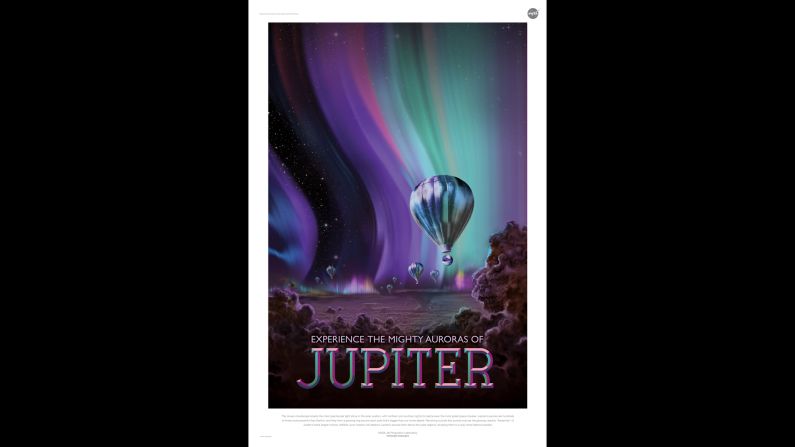

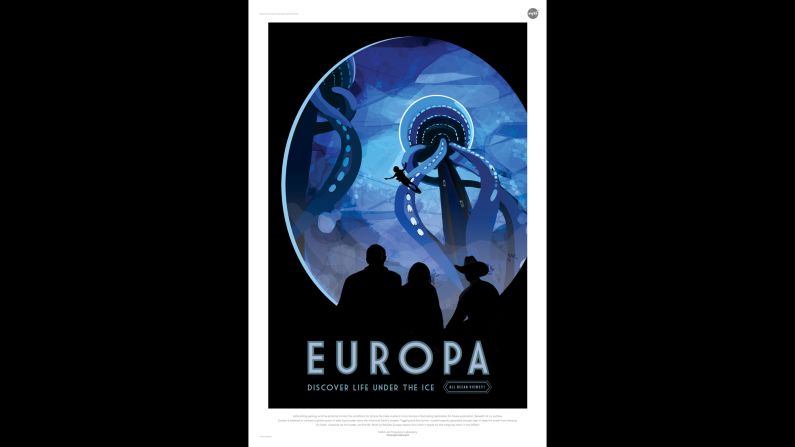

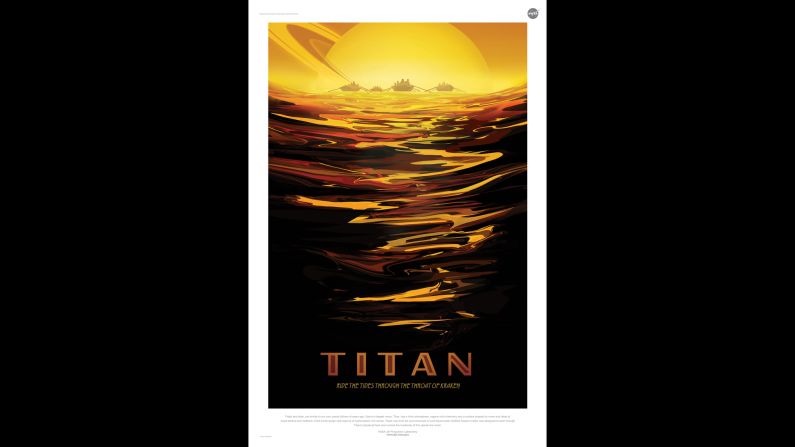

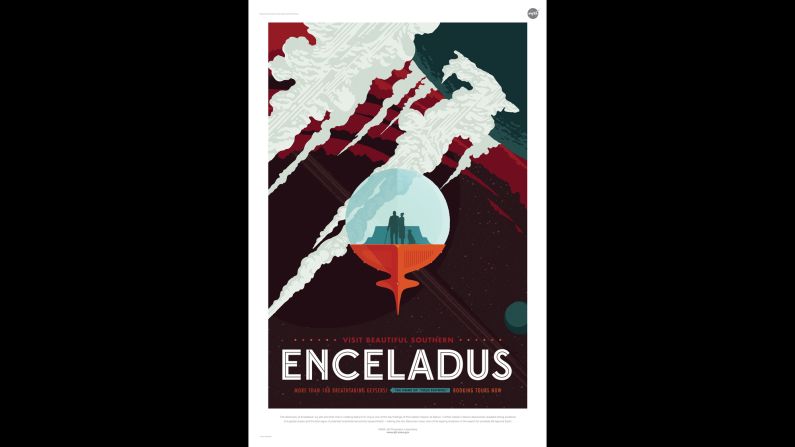

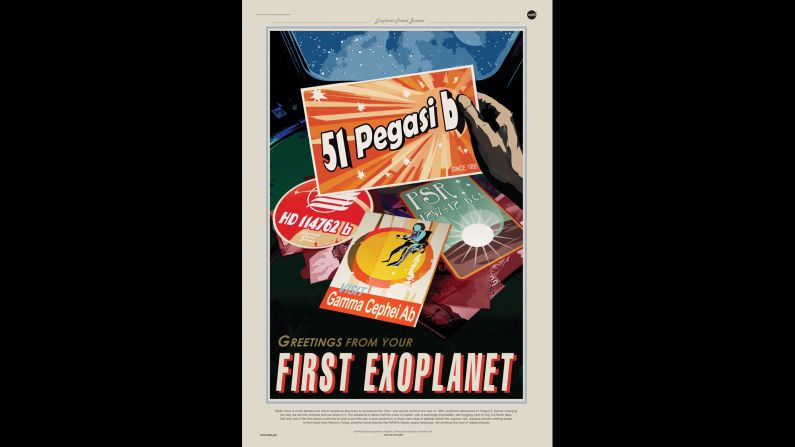

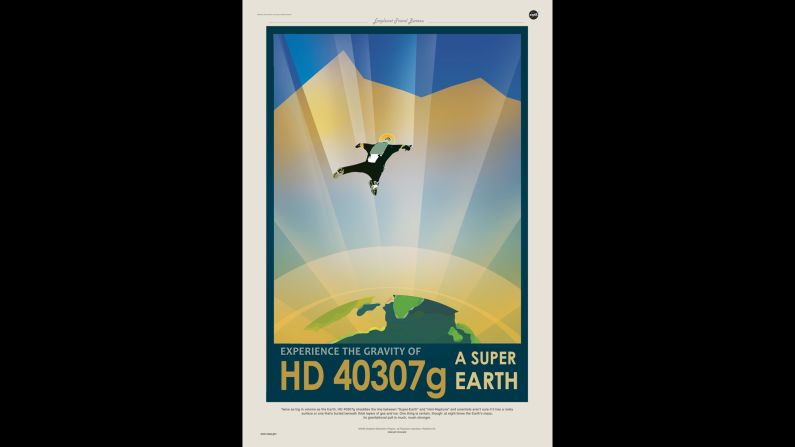

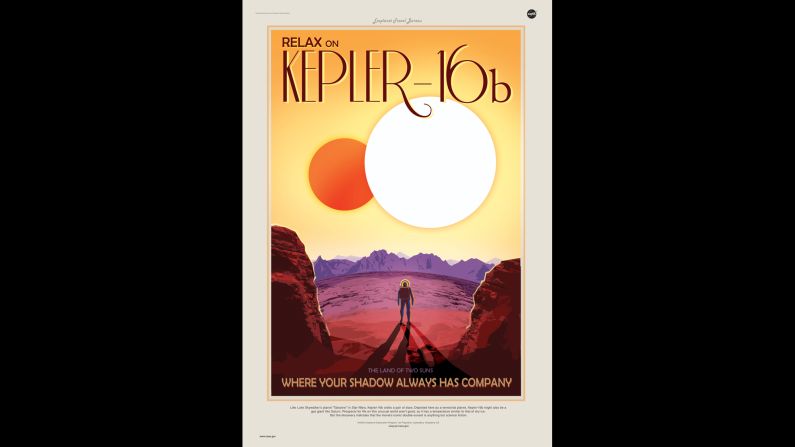

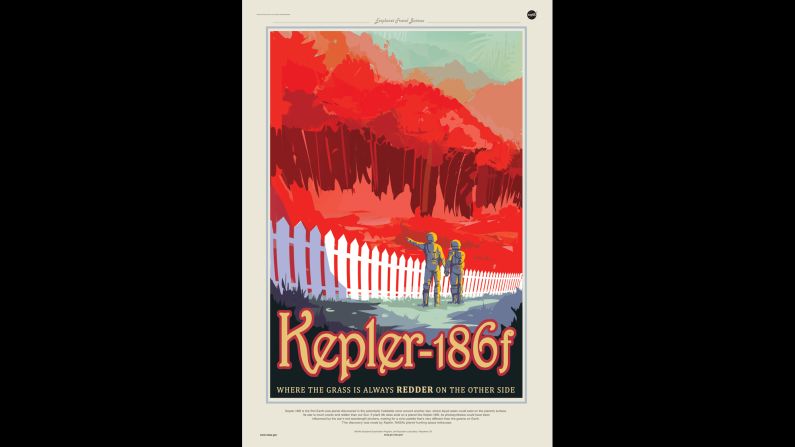

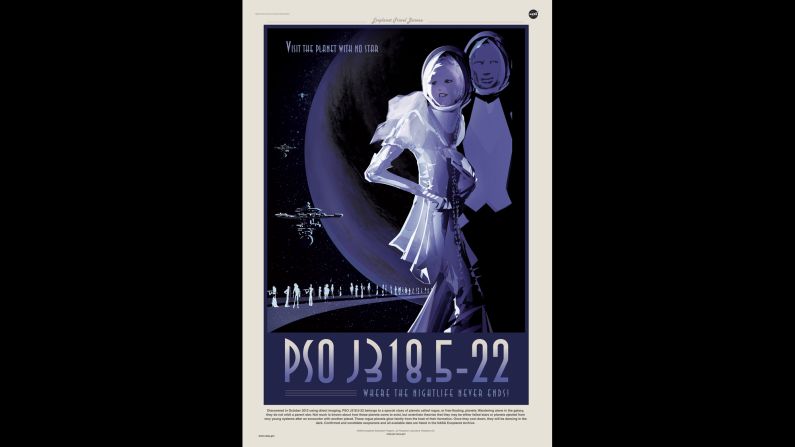

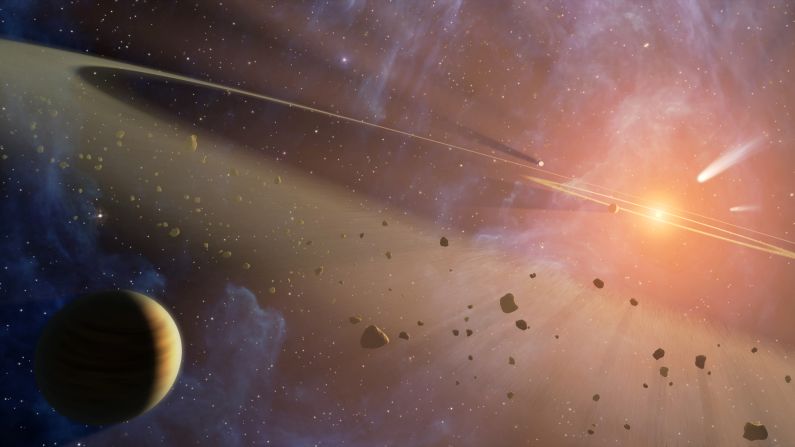

In 2016, they released a series of posters inspired by the Works Progress Administration posters of the late 1930s and early 1940s that encouraged people to visit national parks. The Studio’s “Visions of the Future” posters portrayed places in our solar system being visited by missions, as well as envisioning exoplanets. The posters went viral.

NASA's Exoplanet Travel Bureau

Joby Harris, a visual strategist and designer at The Studio, said they were motivated by the question “why would you want to go there?” He hoped that the exoplanet posters in particular might inspire the next generation to figure out how we might reach them, since current technology would require thousands of years.

The power in the art they’re creating is leaving room for people to create themselves by piquing their interest and inviting their curiosity, he said. It’s a different experience than looking at photos taken by cameras mounted on spacecraft.

“What I love about art that’s so different from photography is that it’s so organic, especially when it has to do with the future,” Harris said. “Art fills in the blanks between the facts where space is undefined. And when data goes through another human, it becomes emotional and real.”

Before working at The Studio, Harris was a concept designer and effects artist for films and TV shows, designing props, spacesuits and spaceships, like the suits seen in “Solaris” and “Star Trek: Enterprise.” The artists work with scientists to talk about ongoing missions in experiential ways and ask what excites them about the missions.

“The posters opened up the value of NASA creating art that ignites peoples imaginations again,” Harris said.

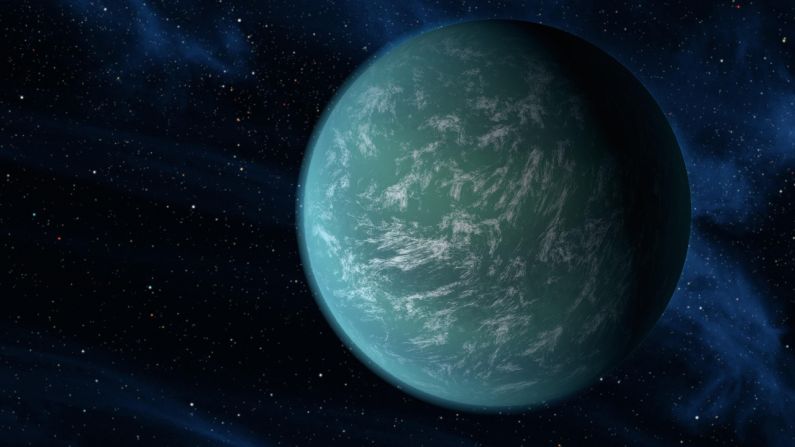

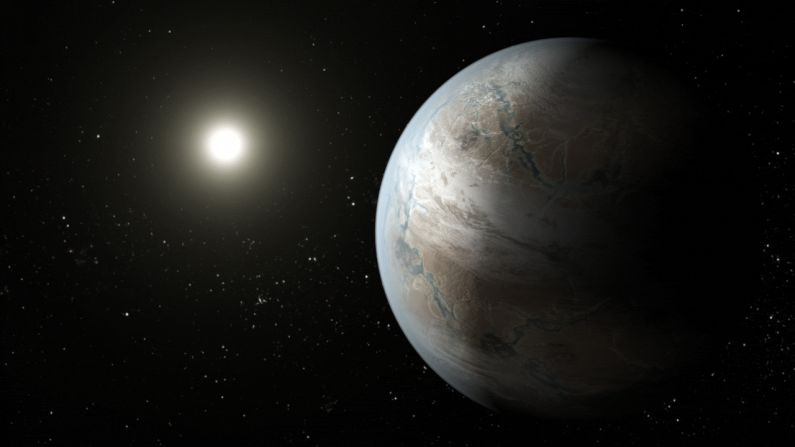

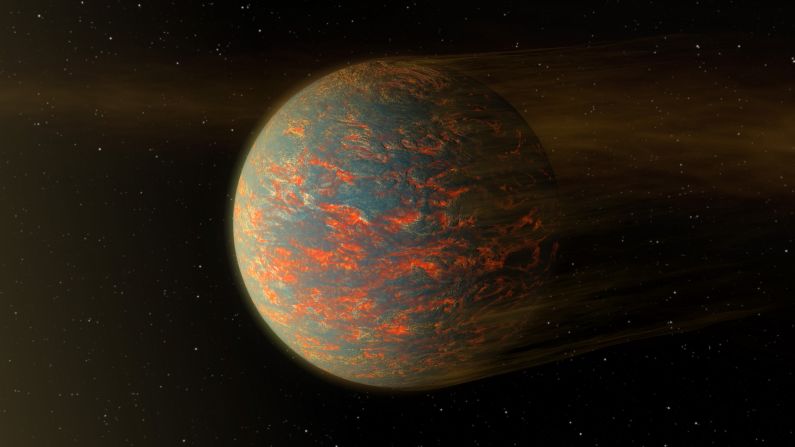

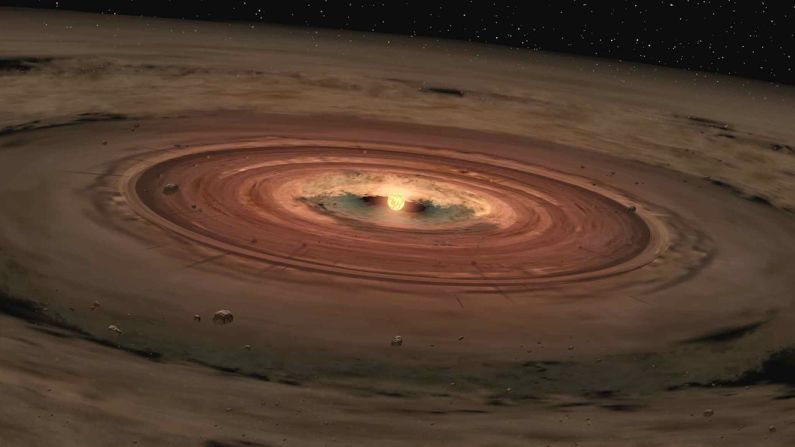

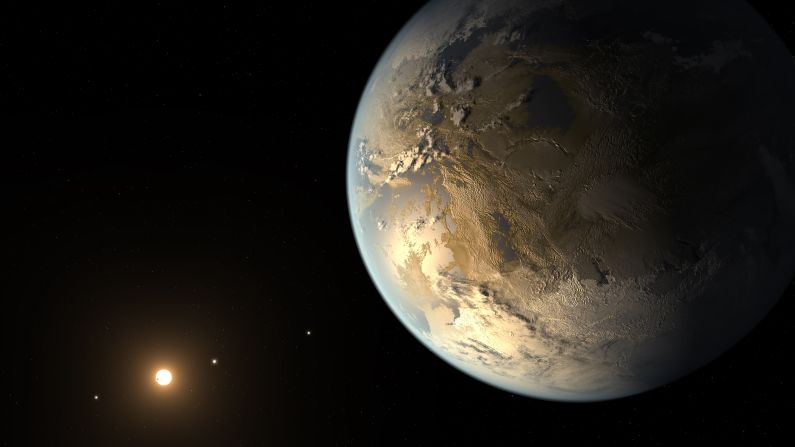

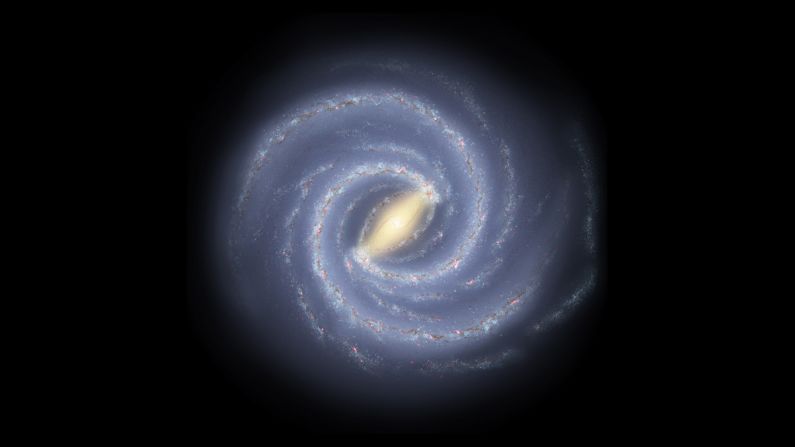

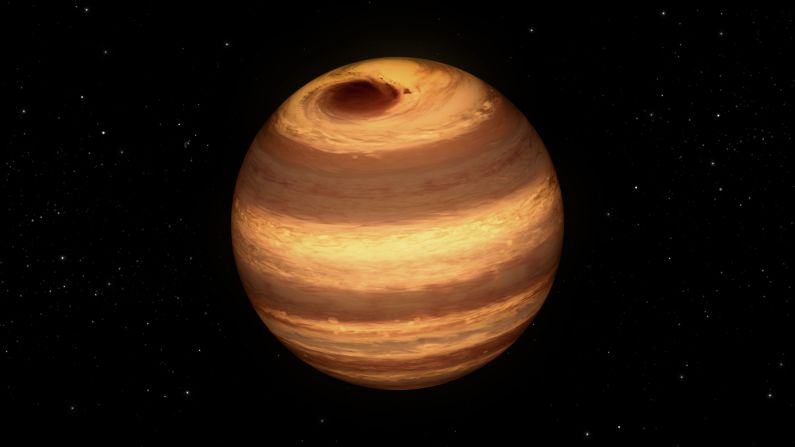

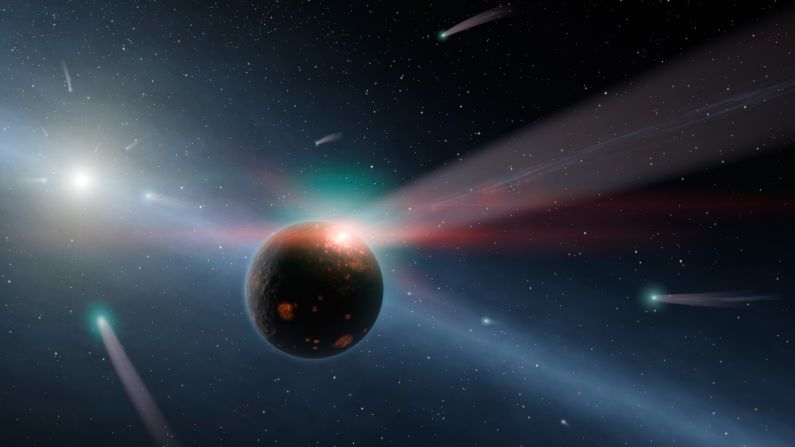

For the past 15 years at Caltech, the artistic duo of Robert Hurt and Tim Pyle has been creating illustrations of how gravitational waves, myriad exoplanets and even the top of the Milky Way might look if we could see them for ourselves. The images look so realistic that the captions have to remind people that they’re artistic renderings.

Hurt took the route of an astronomer in college, and Pyle pursued film production, but both are creative.

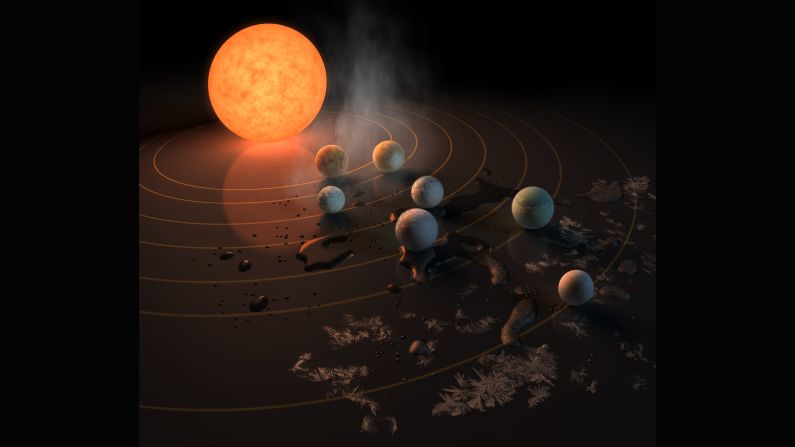

In addition to creating the images that people now associate with the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanet system, found 40 light-years from Earth, Hurt and Pyle have expanded into videos and virtual reality experiences in recent years.

In 2018, they rented a spaceship set for a day and brought in two actors from the TV show “The Expanse” to film an episode of NASA’s “Universe of Learning.” In the five-minute video, the explorers visit a planetary system in hopes of finding a planet in the habitable zone, which may be just the right temperature to support liquid water on its surface and thus life. It offers a play on “The Twilight Zone.”

The material Pyle and Hurt create opens the NASA science releases to cross boundaries. Sometimes, when they sit down with the scientists who author studies on the discoveries of exoplanets and ask “what do you think it looks like?” it’s the first time the scientists have thought about it visually. Then, they literally begin “world-building.”

Up close with alien planets

“At end of day, we want a bullet list of two or three primary science points that we want someone who looks at the image to take in,” Hurt said. “The artwork, by nature, has to fill in thousands of hypotheses of things we don’t know, but as long as all of that is generated around framework of what we do know, that is a successful science illustration. The purpose I really want this artwork to serve is that when someone glances at this image, if they can come into the article already knowing what its about on some level, not only does it drive curiosity, but it promotes understanding.”

And it gives them the perfect position to be some of the first to learn about a scientific discovery. They have the joy of being able to the shape the way the story is told.

Each day could bring a new discovery. They’ve gotten goosebumpy and teary-eyed learning about some of the first detections of things they never thought they’d see in their lifetimes.

So what do they want to illustrate next?

“A life-covered exoplanet would be awesome. And we’re learning more about the origin and history of the universe. But mostly, I’m looking forward to what I don’t know I’m looking forward to,” Pyle said.