Maybe what’s going on with Trump and Congress and executive privilege is relatively tame, since it has to do only with a report on allegations of Russian election interference and obstruction of justice.

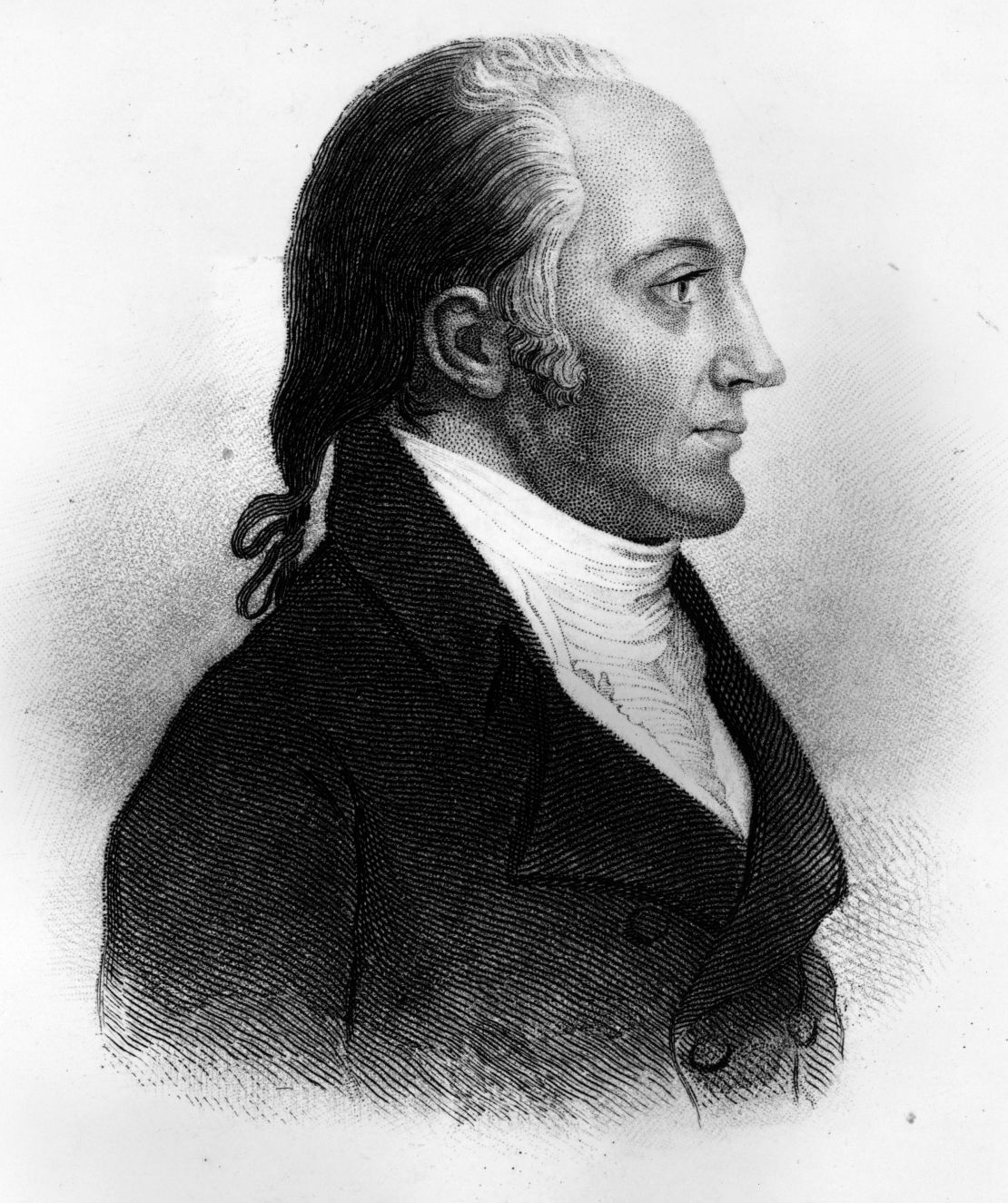

When President Thomas Jefferson argued in 1807 that he didn’t have to fully comply with a subpoena for documents, he was having his former vice president tried for treason for attempting to incite a revolution out West. The former-vice-president-turned-frontier-revolutionary on trial was Aaron Burr, of “Hamilton” dueling fame. The Supreme Court, in the voice of Jefferson’s foil Chief Justice John Marshall, disagreed with the President’s argument, Jefferson ultimately coughed up the documents Burr wanted for his defense and Burr ultimately walked free.

Fast-forward 170 years, and Chief Justice Warren Burger used the Burr trial in deciding that President Richard Nixon had to comply with a subpoena by the special counsel for his taped Oval Office conversations.

None of these cases are exactly the same. Jefferson was responding to a subpoena in a criminal trial. Nixon was responding to a subpoena by a special prosecutor. Trump, in invoking a blanket claim of executive privilege Wednesday, was responding to a subpoena from Congress for the Mueller report.

But they all share the idea that presidents should be able to keep secrets from Congress in order to do their jobs. The term itself – executive privilege – dates back only to the Eisenhower administration. And while it isn’t in the Constitution, the idea has been a matter of considerable debate since George Washington first employed it with regard to congressional inquiries about the postwar Jay Treaty of 1795 between the US and Great Britain.

This is not a secret or under-analyzed subject. Books upon books have been written about it and just about every recent generation has had a knock-down crisis moment fight about it, particularly when presidents have used the idea of executive privilege to cover up missteps.

“The weakest claims of executive privilege involve administrations attempting to cover up embarrassing or politically inconvenient information, or even outright wrongdoing,” write Mark Rozell of George Mason University and Mitchel Sollenberger of the University of Michigan-Dearborn in one study.

They point out, however, that there is a sound need for the president to get candid advice and also to keep information from the public.

“Presidents rely heavily on being able to consult with advisers, without fear of public disclosure of their deliberations,” write Rozell and Sollenberger. “Executive privilege recognizes this notion. Indeed, in U.S. v. Nixon, the Supreme Court not only recognized the constitutionality of executive privilege, but the occasional need for secrecy to the operation of the presidency.”

A brief history

In his memoirs, Nixon expressed regret that he had weakened the principle.

“I was the first president to test the principle of executive privilege in the Supreme Court, and by testing it on such a weak ground, I probably ensured the defeat of my cause,” he wrote.

There has been an ebb and flow ever since.

President Ronald Reagan sought to expand the idea.Bill Clinton tried to use it more than any other president since Watergate as he fought the Whitewater investigation and dealt with fallout from the Monica Lewinsky affair, according to the academics. He ultimately dropped the claim of executive privilege in regard to testimony to Congress about Lewinsky.

Congress considered but ultimately did not move on an impeachment charge against Clinton having to do with abuse of executive privilege, according to Rozell and Sollenberger. Clinton invoked executive privilege 14 times, according to a tally by the Congressional Research Service in 2012, more than twice the tally ofany other modern president.

President George W. Bush tried to expand it even further and strengthen the power of the presidency. He signed an executive order that gave the current president the ability to assert executive privilege over the documents of previous presidents. He also got into snits with Congress over using the idea to shield top aides like Karl Rove from congressional testimony. Back then, CNN’s Jim Acosta reported on where Congress might put someone like Rove in jail if it tried to arrest him. (Yes, Congress can technically arrest people, but it hasn’t tried in more than 70 years.)

President Barack Obama made a big deal of rolling back Bush’s view of executive privilege, but then he asserted it himself on behalf of his attorney general, Eric Holder, who was held in contempt of court over the Fast and Furious gun sale scandal. A federal judge ultimately made Holder turn over documents.

Trump’s claim is different

Trump’s assertion, however, is a blanket assertion of privilege for anything relating to the special counsel report on the Russia investigation. It’s nontraditional in some ways, since privilege is usually asserted for close aides and in Trump’s case it is for an investigation into his administration and 2016 political campaign. It’s also very broad, and seemingly pertains in a protective way to all congressional inquiries related to Mueller.

“This protective assertion of executive privilege ensures the President’s ability to make a final decision whether to assert privilege following a full review of these materials,” wrote Stephen Boyd, a Justice Department official, in a letter Wednesday to the House Judiciary Committee.

“Executive privilege claims customarily come with an underlying rationale such as national security, protecting internal deliberations or protecting ongoing DOJ investigations,” Rozell told CNN in an email. “In this case the President has claimed some ‘protective’ executive privilege which is entirely too broad and without any precedent (excepting equally broad claims such as President Nixon’s that failed the constitutional standard). It seems the President believes he can wall off any and all information or testimony by merely uttering the words ‘executive privilege.’ “

One problem for Democrats right now is that they have asked for essentially every document related to the Mueller report, something they may not ever get.

Timothy Naftali, a New York University historian who’s the former head of the Nixon presidential library, said Wednesday on CNN that they should be more specific and detailed in their requests.

“I think at this moment a lot of Americans are just seeing the Republicans and Democrats screaming at each other, and the details – which are so important – are being lost,” he said, arguing that Trump is making his broad claim of privilege because he thinks most people will see only the political back and forth rather than understand what, specifically, Democrats are trying to get.

“Usually disputes over executive privilege get resolved through an accommodation process between Congress and the White House,” Rozell observed. “We seem to be stuck now in a zero-sum game with each side digging in.”

Regardless, this is now a fight destined for the courts. And these things take time. It took a year from the time Nixon refused to release the tapes till the Supreme Court ruled against him. It was four years from the time Obama made his executive privilege claim regarding Fast and Furious before a judge rejected it. And even then the legal fight over the documents continued into the Trump administration.

Indeed, just on Wednesday the Democrat-led House and the Justice Department announced to a federal appeals court in Washington that they had reached a settlement in the Fast and Furious court case.