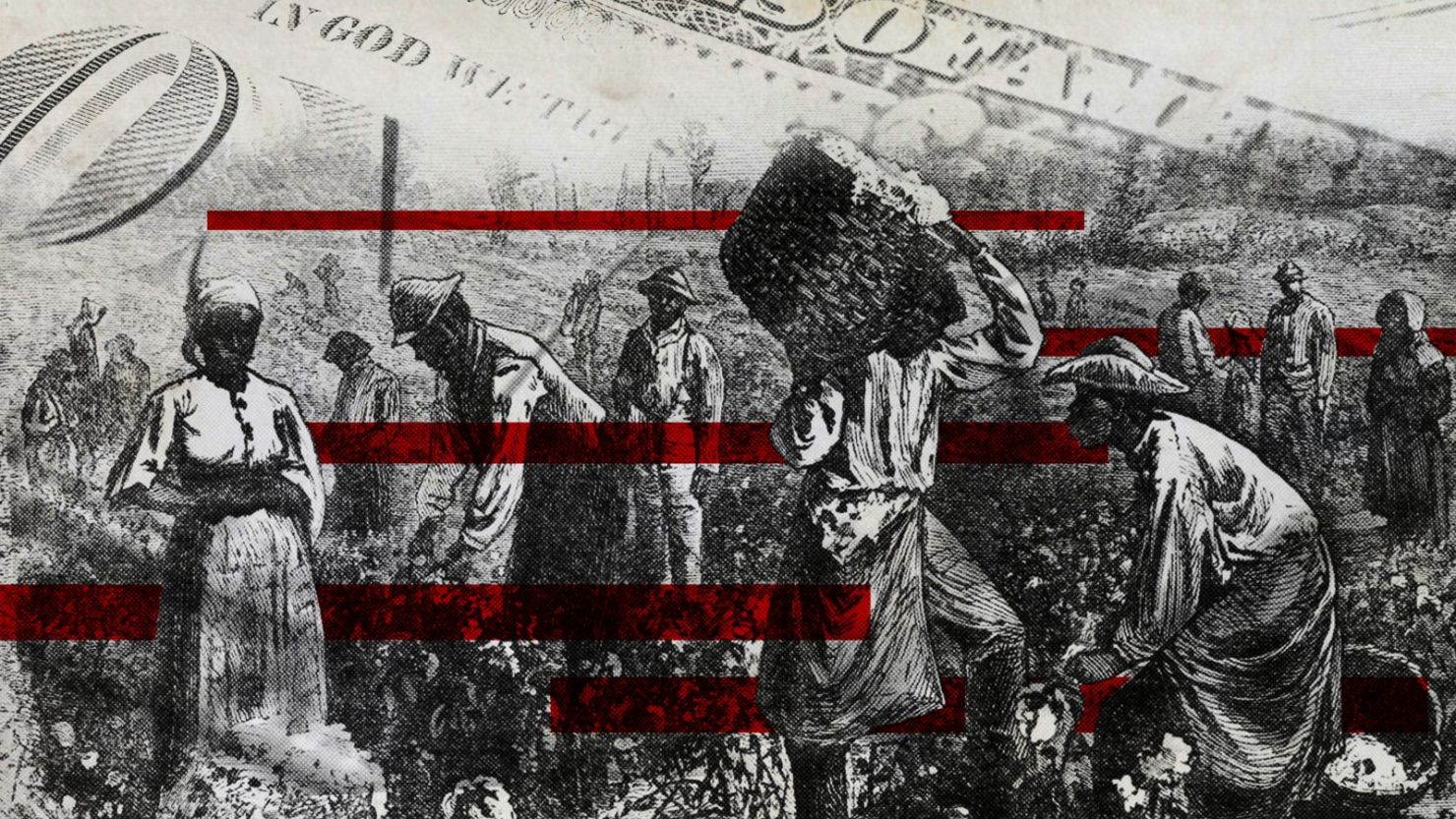

W. Kamau Bell visits New Orleans to explore the topic of reparations on “United Shades of America” Sunday, August 16 at 10 p.m. ET.

If you feel like you’re hearing more about slavery reparations, it’s not your imagination.

The widespread protests against police brutality and racial injustice following the death of George Floyd have brought a new urgency to the debate around compensating the descendants of American slaves.

This summer, Democratic lawmakers called for a vote on a bill to study reparations, and a handful of cities and states have weighed in with their own proposed plans to examine the issue.

But just how would reparations, focused specifically on slavery, work? Read on for background on this complex and thorny subject.

Why are reparations in the news?

The idea of giving Black people reparations for slavery dates back to right after the end of the Civil War (think 40 acres and a mule). For decades, it’s mostly been an idea debated outside the mainstream of American political thought.

But writer Ta-Nehisi Coates reintroduced it to the mainstream with his 2014 piece in The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations.” Since then, the conversations surrounding reparations have intensified.

Last year it was a hot topic on the campaign trail, with Democratic presidential candidates voicing support for slavery reparations.

Presumptive Democratic presidential nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden told The Washington Post he supports studying how reparations could be part of larger efforts to address systemic racism. Biden’s newly appointed running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, has co-sponsored a bill that would study the effects of slavery and create recommendations for reparations.

And in the midst of America’s current racial reckoning, reparations are being explored on the local level, too.

In June, the California Assembly passed a bill to create a reparations task force, moving the legislation on to the state’s senate. In July, the city of Asheville, North Carolina, voted unanimously to approve a reparations resolution for Black residents.

And that same month, the mayor of Providence, Rhode Island, signed an executive order to pursue “truth, reconciliation and municipal reparations” for Black Americans, Indigenous people and people of color in the city.

How do you put a cash value on hundreds of years of forced servitude?

This may be the most contested part. Academics, lawyers and activists have given it a shot, though, and their results vary.

Most formulations have produced numbers from as low as $17 billion to as high as almost $5 trillion.

– The most often-quoted figure, though, is truly staggering, as anthropologist and author Jason Hickel notes in his 2018 book, “The Divide: Global Inequality from Conquest to Free Markets”:

“It is estimated that the United States alone benefited from a total of 222,505,049 hours of forced labor between 1619 and the abolition of slavery in 1865. Valued at the US minimum wage, with a modest rate of interest, that is worth $97 trillion today.”

Other formulations are more modest. Research conducted by University of Connecticut associate professor Thomas Craemer amounted to an estimate of nearly $19 trillion (in 2018 dollars).

As Craemer explains to W. Kamau Bell in Sunday’s episode of “United Shades of America,” he came up with that figure by estimating the size of the enslaved population, the total number of hours they worked and the wages at which that work should have been compensated, compounded by 3% interest.

However, Craemer notes in a 2020 report that this estimated total is still conservative because he only deals with the slavery that happened from the time of the country’s founding until the end of the Civil War, so his estimate doesn’t account for slavery during the colonial period or the decades of legalized segregation and discrimination against Black Americans that followed emancipation.

Where would the money come from?

Generally, advocates for reparations say that three different groups should pay for them: federal and state governments, which enshrined, supported and protected the institution of slavery; private businesses that financially benefited from it; and rich families that owe a good portion of their wealth to slavery.

“There are huge, wealthy families in the South today that once owned a lot of slaves. You can trace all their wealth to the free labor of Black folks. So, when you identify the defendants, there are a vast number of individuals,” attorney Willie E. Gary told Harper’s Magazine in November 2000, during the height of the last, big time of reparations talk. Gray was talking about how these families could be sued for reparations since they benefited directly from slavery.

As you might imagine, suing large groups of people to pay for reparations wouldn’t go over well. Others have suggested lawmakers could pass legislation to force families to pay up. But that might not be constitutionally sound.

“I don’t think you can legislate and have those families pay,” Malik Edwards, a law professor at North Carolina Central University, told CNN. “If you’re going to go after individuals you’d have to come up with a theory to do it through litigation. At least on the federal level Congress doesn’t have the power to go after these folks. It just doesn’t fall within its Commerce Clause powers.”

The Commerce Clause refers to the section of the US Constitution which gives Congress the power to regulate commerce among the states.

But reparations mean more than a cash payout, right?

It could. Reparations could come in the form of special social programs or land resources. It could mean a mix of cash and programs targeted to help Black Americans.

“Direct benefits could include cash payments and subsidized home mortgages similar to those that built substantial White middle-class wealth after World War II, but targeted to those excluded or preyed upon by predatory lending,” Chuck Collins, an author and a program director at the Institute for Policy Studies, told CNN. “It could include free tuition and financial support at universities and colleges for first generation college students.”

Reparation funds could also be used to provide one-time endowments to start museums and historical exhibits on slavery, Collins said.

In the case of Asheville, the city council resolution does not mandate direct cash payments to descendants of slaves. Instead, the city plans to make investments in areas where Black residents face disparities.

What are the arguments against reparations?

There are many. Opponents of reparations argue that all the slaves are dead, no White person living today owned slaves or that all the immigrants that have come to America since the Civil War don’t have anything to do with slavery. Also, not all Black people living in America today are descendants of slaves (like former President Barack Obama).

Last year, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said he opposed the idea, arguing “none of us currently living are responsible” for what he called America’s “original sin.”

Others point out that slavery makes it almost impossible for most African Americans to trace their lineage earlier than the Civil War, so how could they prove they descended from enslaved people?

Writer David Frum noted those and other potential obstacles in a 2014 piece for The Atlantic entitled “The Impossibility of Reparations,” which was a counterpoint to Coates’ essay. Frum warned that any reparations program would eventually be expanded to other groups, like Native Americans, and he feared that reparations could create their own brand of inequality.

“Within the target population, will all receive the same? Same per person, or same per family? Or will there be adjustment for need? How will need be measured?” asks Frum, a former speechwriter for President George W. Bush. “And if reparations were somehow delivered communally and collectively, disparities of wealth and power and political influence within Black America will become even more urgent. Simply put, when government spends money on complex programs, the people who provide the service usually end up with much more sway over the spending than the spending’s intended beneficiaries.”

In a column for The Hill last year, conservative activist Bob Woodson decried the idea of reparations as “yet another insult to Black America that is clothed in the trappings of social justice.” He also told CNN he feels America made up for slavery long ago, so reparations aren’t needed.

“I wish they could understand the futility of wasting time engaging in such a discussion when there are larger, more important challenges facing many in the Black community,” Woodson, the founder and president of the Woodson Center, told CNN. “America atoned for the sin of slavery when they engaged in a civil war that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Let’s for the sake of argument say every Black person received $20,000. What would that accomplish?”

This isn’t the first time reparations have come up, is it?

After decades of languishing as something of a fringe idea, the call for reparations really caught steam in the late 1980s through the ’90s.

Former Democratic Rep. John Conyers first introduced a bill in 1989 to create a commission to study reparations. Known as HR 40, Conyers repeatedly re-introduced the bill, which has never been passed, until he left office in 2017. Texas Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee has taken up the HR 40 baton.

Activist groups, like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America and the Restitution Study Group, sprang up during this period. Books, like Randall Robinson’s “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” gained huge buzz.

Then came the lawsuit. In 2002 Deadria Farmer-Paellmann became the lead plaintiff in a federal class-action suit against a number of companies – including banks, insurance company Aetna and railroad firm CSX – seeking billions for reparations after Farmer-Paellmann linked the businesses to the slave trade.

She got the idea for the lawsuit as she examined old Aetna insurance policies and documented the insurer’s role in the 19th century in insuring slaves. The suit sought financial payments for the value of “stolen” labor and unjust enrichment and called for the companies to give up “illicit profits.”

“These are corporations that benefited from stealing people, from stealing labor, from forced breeding, from torture, from committing numerous horrendous acts, and there’s no reason why they should be able to hold onto assets they acquired through such horrendous acts,” Farmer-Paellmann said at the time.

The case was tossed out by a federal judge in 2005 because it was deemed that Farmer-Paellmann and the other plaintiffs didn’t have legal standing in the case, meaning they couldn’t prove a sufficient link to the corporations or prove how they were harmed. The judge also said the statute of limitations had long since passed. Appeals to the US 7th Circuit Court of Appeals and the US Supreme Court proved unsuccessful, and the push for reparations kind of petered out.

But Coates’ 2014 article in The Atlantic reignited interest in the issue. New reparations advocacy groups, like the United States Citizens Recovery Initiative Alliance Inc., took up the fight. Black Lives Matter includes slavery reparations in its list of proposals to improve the economic lives of Black Americans. Even a UN panel said the US should study reparations proposals.

So, what are the prospects of reparations moving forward?

Slavery reparations still face an uphill battle.

The idea isn’t popular with the American public. A 2020 poll from The Washington Post and ABC News found that 63% of Americans don’t think the US should pay reparations to the descendants of slaves. Unsurprisingly there’s a racial divide to this. The Post-ABC News poll found that while 82% of Black Americans support reparations, 75% of White Americans don’t.

After the failure in the courts of Farmer-Paellmann’s lawsuit more than a decade ago, taking legal action to secure reparations doesn’t seem like the most promising route either.

Still, the HR 40 bill – titled “H.R.40 - Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act” – continues to make the rounds in Congress.

The bill calls for a commission that “aims to study the impact of slavery and continuing discrimination against African-Americans, resulting directly and indirectly from slavery to segregation to the desegregation process and the present day,” said Jackson Lee.

Her office said it has the support of 128 members of the House – more than half of the Democratic caucus.

The bill’s next stop is a full committee hearing, followed by a vote in the House.

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer’s office told CNN that the bill will get a vote if it comes out of committee.

Whatever happens, there is wide agreement that something needs to be done to cut down the huge wealth gap between Whites and Blacks that slavery helped create. Chuck Collins, the author and scholar, said his own research showed that the median wealth of a White household is $147,000, which is about 41 times greater than the median wealth of a Black family, which is $3,600.

“This can only be explained through an understanding of the multigenerational legacy of White supremacy in asset building,” he told CNN.

“People say, ‘slavery was so long ago’ or ‘my family didn’t own slaves.’ But the key thing to understand is that the unpaid labor of millions – and the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow laws, discrimination in mortgage lending and a race-based system of mass incarceration – created uncompensated wealth for individuals and White society as a whole. Immigrants with European heritage directly and indirectly benefited from this system of White supremacy. The past is very much in the present.”

NOTE: A version of this piece previously appeared in April 2019.

CNN’s Zachary B. Wolf, Veronica Stracqualursi, Sunlen Serfaty and Shawna Mizelle contributed to this report.