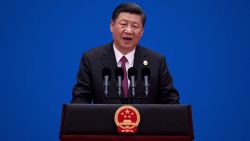

Two years ago, Indonesian President Joko Widodo – also known as Jokowi – stood shoulder to shoulder with Xi Jinping for a group photo to celebrate the Chinese leader’s Belt and Road project.

Yet now, as Jokowi seeks re-election, he appears to be distancing himself from Beijing and downplaying the importance of Chinese-funded projects in Indonesia.

It’s a pattern emerging across southeast Asia and beyond, and one that will be of great concern for Beijing as Chinese investment and ties become an awkward – if not downright toxic – election issue.

The growing skepticism over Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) risks exacerbating existing tensions many countries in the region have with Beijing over territorial disputes, as both China and the US continue to jockey for power amid a drawn-out trade war.

Better deal

“It is not true if people think President Jokowi has special preference for China-funded projects,” his spokesman Ace Hasan Syadzily said last week.

If Widodo’s camp sounds defensive, it’s because his alleged ties to Beijing have become a key attack line for rival Prabowo Subianto. After Jokowi undercut Prabowo’s criticisms of him being not Muslim enough by selecting an Islamist cleric as his running mate, the retired general has gone hard after Chinese investments in Indonesia once touted by the President.

In January, Prabowo – echoing US President Donald Trump – vowed to get a “better deal” from Beijing, and called for Jakarta to review its trade policies with China.

Anwita Basu, an analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit, said that “over the course of the campaign period, anti-China rhetoric has been on the rise.”

“The Chinese community in Indonesia – who have mainly been business owners and traders - have long faced resentment and discrimination for controlling large amounts of wealth,” she told CNN by email. “These issues are touted and popularized during election periods and this year, (Prabowo) has used them as a means to question Jokowi’s loyalty to his own nation.”

China is Indonesia’s biggest trading partner by far, according to the World Bank. In the first two months of this year, trade between the two countries was worth more than $10.4 billion.

Under Jokowi, Indonesia has joined both the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank as well as Xi’s BRI. The initiative has come under increasing criticism in recent months, amid claims it saddles poorer countries with unsustainable debts and projects that benefit Beijing more than host nations.

Beijing has funded major infrastructure projects in Indonesia, most notably a $6 billion high-speed railway linking Jakarta with the city of Bandung, the capital of West Java.

That project is due to be completed next year. But it has come under criticism for alleged budget overruns, poor planning and construction delays. Even supporters of greater Chinese investment in Indonesia have turned on it – Tom Lembong, the country’s investment chief, told Bloomberg it “represents everything that’s wrong with Belt and Road.”

“It’s opaque and non-transparent – even us cabinet members are having trouble getting data and information,” Lembong said.

Running on anti-China

While the Indonesian election still seems Jokowi’s to lose, and a Prabowo presidency appears to be a long shot, recent history shows Beijing can little afford to be complacent.

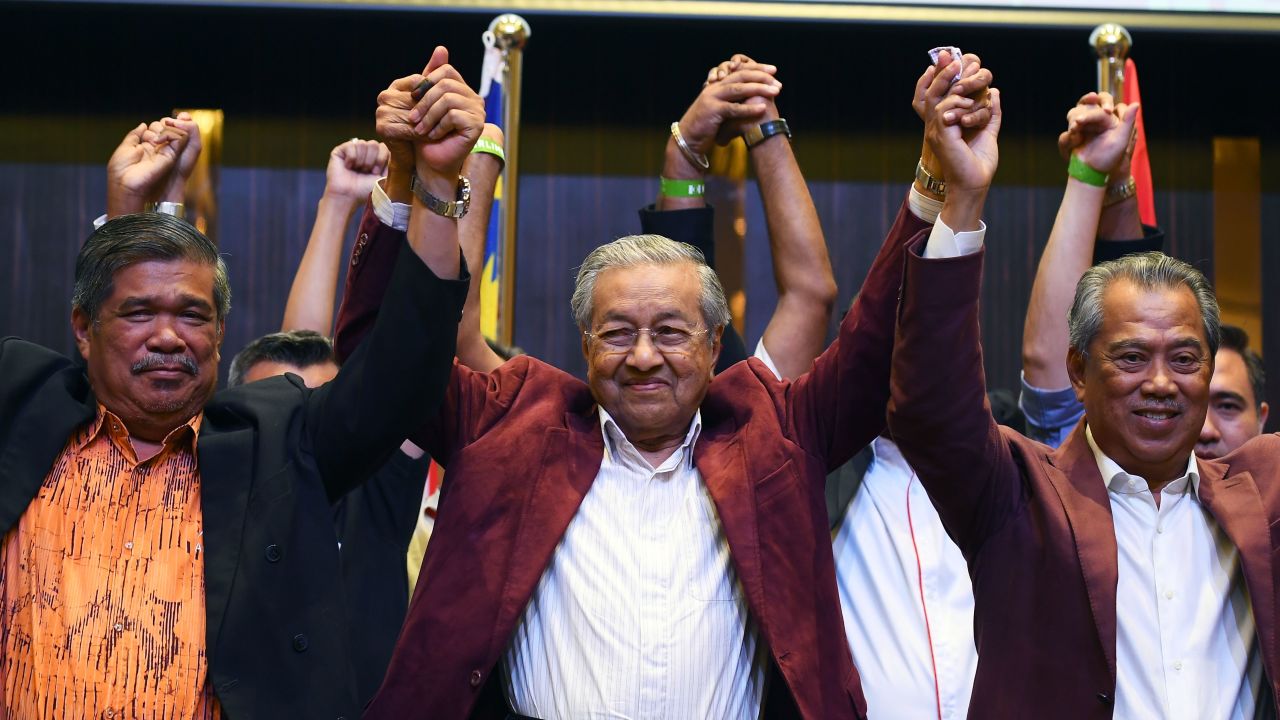

Chinese investment and alleged influence played a role in Malaysia’s elections last year. And while it was not the driving factor in Mahathir Mohamad’s upset victory in May, the 93-year-old has followed through on promises to be tougher on Beijing since becoming President.

Nor were such concerns limited to the Malaysian election. During a poll in the Maldives last year, incumbent and eventual loser Abdulla Yameen was repeatedly attacked over his close ties to Beijing.

In January 2018, former President Mohamed Nasheed accused Yameen of allowing China to stage a “land grab” in the country. After his Maldivian Democratic Party took power, it pledged to end “China’s colonialism” and renegotiate loans with Beijing.

Other countries, such as Myanmar, have scaled back BRI projects amid concerns over debt and sustainability.

Beyond Asia, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta faced claims – which he dismissed as “pure propaganda” – that a key port in Mombasa was at risk of being seized by Beijing over unpaid debts. The public relations storm was sparked by an actual move by China to take over Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port, after the country could not pay back the billions of dollars it owed Beijing.

China has vigorously pushed back against such criticism, saying it is being subjected to double standards.

“It is unreasonable that money coming out of Western countries is praised as good and sweet, while coming out of China it’s sinister and a trap,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Hua Chunying said in September.

Losing its sheen

As China prepares for a key Belt and Road summit later this month, there are signs Beijing is looking to overhaul the initiative in an attempt to address some of its most pressing issues and defuse criticisms from foreign partners.

While she felt the backlash against China in countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia was outweighed by others like the Philippines moving closer to Beijing, EIU analyst Basu predicted “many countries will remain cautious over the lack of transparency in the terms of funding offered” for BRI deals.

The backlash against BRI, which appears to have caught Chinese leaders off guard, has highlighted that beyond investment, Beijing has little to offer its neighbors – many of which are either neutral or opposed to it on key foreign policy issues.

“China’s increasingly assertive policy in the South China Sea since 2009 has reinforced concerns about whether the country’s rise will continue to be peaceful, especially in light of Beijing’s perceived role in undermining Asean unity,” Jakarta-based political analyst Dewi Fortuna Anwar wrote last month.

Both Indonesia and Malaysia have territorial disputes with China, and in December Jokowi oversaw the opening of a military base on the Natuna Islands at the southern tip of the South China Sea. Malaysia too has expressed concern over Beijing’s sprawling claims in the disputed waters.

Governments in the two Muslim-majority countries are also facing increasing pressure to stand up to China over its treatment of the Uyghur minority, hundreds of thousands of whom have allegedly been sent to “re-education” camps amid a wider crackdown on Islam.

As it attempts to balance an increasingly hostile US – and ward off the ill effects of a temporarily paused trade war with Washington – China is finding that its traditional methods of winning friends in Asia is losing its sheen. And the closer it gets to superpower status, the more its influence and power can be used against it.