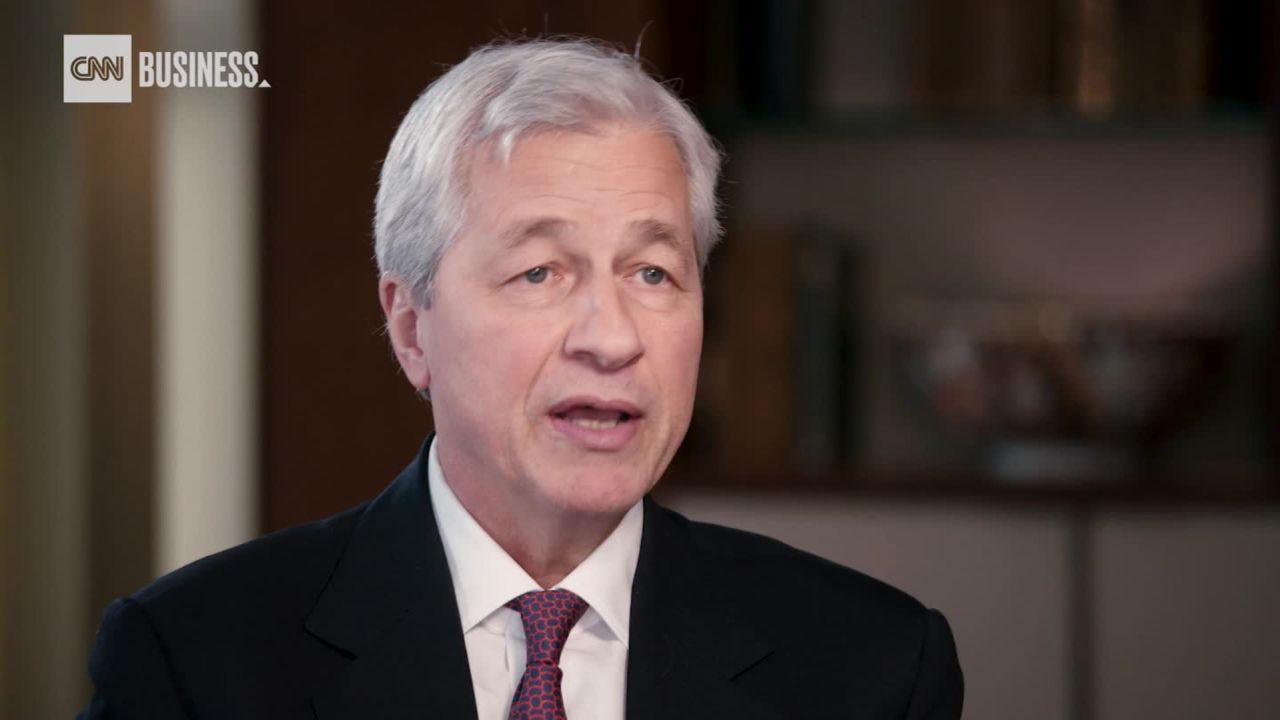

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon talks a lot about the need to train workers for the jobs of the future. Now the bank says it will spend $350 million over the next five years to make it happen.

The company, which previously made a $250 million five-year commitment to job training in 2013, said Monday it will invest in a variety of initiatives, including a development program for community college presidents and new research.

“The new world of work is about skills, not necessarily degrees,” Dimon said in a statement. “Unfortunately, too many people are stuck in low-skill jobs that have no future and too many businesses cannot find the skilled workers they need.”

One of the bank’s projects will be in partnership with the Aspen Institute. JPMorgan (JPM) will fund a program for community college presidents that will focus on curriculum development, boosting graduation rates and helping students secure good jobs after graduation.

JPMorgan will also team up with PolicyLink, a think tank focusing on economic and social equality, and the National Fund for Workforce Solutions, a nonprofit that advocates for better job training. The collaboration will generate workforce data in 10 US cities. It’s meant to help identify job training opportunities in those areas, particularly for disadvantaged groups.

Additionally, the bank will work with MIT to identify where more job training is necessary within JPMorgan’s own workforce.

“Building a future-ready workforce is a key priority,” Robin Leopold, JPMorgan’s head of human resources, said in a press release. “That is why we are proactively identifying the skills we need and understanding the skills and education our employees have.”

About 75% of the US positions the bank posted in 2018 didn’t require a college degree, she added.

“How many college graduates do you think want to be a teller? Very few,” Dimon said at an event in New York on Monday announcing the initiative. He said the bank probably made a mistake, from a business standpoint, in requiring a college degree for some positions.

Dimon added that companies need to work with local government and education systems to get people the skills they need to fill open jobs.

“These problems are not aging well,” he said.

The US economy has added jobs for the last 101 months. But the United States has long struggled with a skills gap that can make it hard for companies to find qualified candidates for certain positions — the result of the rapid pace of automation, and a lack of effective training programs.