Beto O’Rourke entered the 2020 presidential race on Thursday, beginning his bid to recapture what made him a star during his Senate race last year while facing for the first time the larger Democratic electorate.

O’Rourke joins a crowded field of more than a dozen Democrats as a wildcard. As with his Senate bid, O’Rourke is building his presidential campaign around an aspirational, Barack Obama-esque call to move past partisan politics – heavy on emotional appeal and fueled by the force of his own personality. But he has not clearly defined himself in terms of what he actually believes or where his ideology will fit among a group of candidates who range from progressive to more moderate.

“The only way for us to live up to the promise of America is to give it our all and to give it for all of us,” O’Rourke said in his announcement video. “We are truly now, more than ever, the last great hope of Earth.”

The former US congressman enters as a formidable candidate. He rose to superstardom within the Democratic Party in 2018, raising $80 million and building a national following during his close loss to Republican Sen. Ted Cruz.

Even though he served three terms in Congress, he’s carved out an image as an outsider, mainly by running an unconventional campaign in Texas. His willingness to livestream his life on Facebook was a stylistic break from most politicians and helped create viral moments – leading millions of people to watch him defend NFL players who kneel during the National Anthem, see him skateboard through a Whataburger parking lot and switch from English to Spanish and back at town halls. Those moments will now play out on a bigger stage among candidates who take a more traditional approach to campaigning.

Can he recapture 2018’s energy?

O’Rourke’s entry into the race concludes a four-month stretch of public indecision. And as O’Rourke waited, the Democratic presidential field rapidly took shape around him.

“I think his chance in the fall was unique in that the Democratic Party felt really good after the elections, but we felt like we didn’t really have any superstars in the party, and he was seen as one of the only superstars,” said Sean Bagniewski, the Democratic chairman in Iowa’s Polk County.

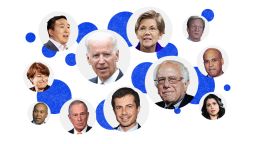

“But in the time since then, you know, you’ve got Joe Biden coming in – Joe Biden’s a superstar. Bernie, Kamala, Cory, Warren,” Bagniewski said. “Their stocks have gone up in the meantime.”

The early days of O’Rourke’s candidacy will begin to provide answer to one of the central questions of his campaign: Can he recapture the enthusiasm for his 2018 Senate race and harness it to win a presidential election?

In the months before his decision, O’Rourke took a road trip through several western states, writing on Medium while he traveled that he was “stuck lately. In and out of a funk.”

Most of his public political activity in that period has been focused on countering President Donald Trump on the border wall. O’Rourke staged a counter-rally when Trump visited El Paso, drawing thousands of supporters to an event opposing Trump’s calls for a wall. He continued the livestreams, talking about the safety of his community on the US-Mexico border and interviewing people he ran across – including, famously, his dental hygienist, on Instagram, while she had tools in his mouth – about life at the border.

As he moved toward a run for president, O’Rourke was also grappling with the realities of his sudden rise to political stardom: He was now a leading figure in a Democratic Party with which he had never really built strong connections.

O’Rourke’s father had switched from being a Democrat to a Republican as a local politician in El Paso. O’Rourke entered the House after ousting an incumbent Democrat in a primary. Once he was there, O’Rourke didn’t pay dues to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and, citing his support for term limits, wouldn’t vote to re-elect Nancy Pelosi as House minority leader in 2016. Then, during his Senate run, he swore off consultants and refused to hire a pollster.

It all left him with a thin roster of aides and associates with presidential campaign experience, compared to other Democratic contenders who spent months or even years preparing for the race.

His itinerary for his first three-day swing through Iowa offers a glimpse of how O’Rourke plans to approach the race. He is visiting eight counties that Obama won in 2012 and then Donald Trump won in 2016 – the sort of territory Democrats were accused of ignoring.

That matches O’Rourke’s tactics in last year’s Senate campaign. Even as Democrats made their most substantial gains in 2018’s elections in the urban regions of Texas, O’Rourke spent much of his campaign traveling to forgotten rural territory where supporters said they hadn’t seen a statewide candidate in decades, ultimately visiting all 254 counties in the state.

O’Rourke’s ability to draw huge crowds to places that had never before been on the political map – including heavily Republican portions of Texas – fed into perceptions of him as an inspirational, post-partisan figure similar to Obama in 2007. Obama and O’Rourke met in December, and in a podcast with former senior strategist David Axelrod, Obama praised O’Rourke’s Senate run.

“What I liked most about his race was that it didn’t feel constantly poll-tested,” Obama said. “It felt as if he based his statements and his positions on what he believed. And that, you’d like to think, is normally how things work. Sadly, it’s not.”

But O’Rourke is stepping into a much different political environment than Obama had entered.

In the Texas Senate race, O’Rourke became a Democratic superstar in part because of who he was running against. He could campaign on a more inclusive approach to politics because Cruz had built his personal brand on fighting against everything Obama was for. In a Democratic primary, though, he enters as just one of 15 candidates, all of whom have sharply criticized Trump’s policies and approach to politics.

“The best day of Beto’s campaign may have been about two months ago. Before the self-described ‘funk,’ before the self-indulgent road trip, before live-streaming his visit to the dental hygienist,” said Democratic strategist Krystal Ball. “I think it will be hard for Democrats to imagine that the way to win back the Midwest is with a privileged emo dude who couldn’t beat the most hated man in the Senate.”

Still, O’Rourke has signaled he doesn’t plan to change his approach. Toward the end of his January road trip, O’Rourke took to Medium again to lay out his own views.

“How do we come together? How do we stop seeing each other as outsiders? How do we reconcile our differences, account for the injustices visited upon so many, understand the pride that each of us feels for ourselves, our families, our point of view – and respond to the urgent needs of this great democracy at its moment of truth? As the country literally begins to shut down, how can we come together to revive her?” he wrote.

“I know we can do it. I can’t prove it, but I feel it and hear it and see it in the people I meet and talk with. … It’s complicated. But a big part of it has got to be just listening to one another, learning each other’s stories, thinking ‘whatever affects this person, affects me.’ We’re in this together, like it or not. The alternative is to be in this apart, and that would be hell.”

Questions about views

In addition to his approach to politics, now, for the first time, O’Rourke is also going to face tough questions about his views on policy.

Where O’Rourke fits into the race ideologically is less clear compared to progressive bulwarks like Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and candidates with a more centrist approach, like Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former Vice President Joe Biden.

In Congress, his voting record was moderate. He advocated free trade and was a member of the centrist New Democrat Coalition.

But O’Rourke has also taken progressive positions on issues like criminal justice. He has long advocated marijuana legalization. During last year’s Senate race, he embraced “Medicare for all” and said he would support impeaching Trump. This year, he caused a stir by saying he would tear down the border wall that already exists between El Paso and Mexico.

He’s also facing a reality that could hurt him, Biden and Sanders: Women and people of color make up much of the Democratic base – and many activists within the party say they would prefer not to nominate another white man.

In a Vanity Fair profile released Wednesday, O’Rourke said he would build a campaign and administration that “looks like this country.”

“But I totally understand people who will make a decision based on the fact that almost every single one of our presidents has been a white man, and they want something different for this country,” he said. “And I think that’s a very legitimate basis upon which to make a decision. Especially in the fact that there are some really great candidates out there right now.”