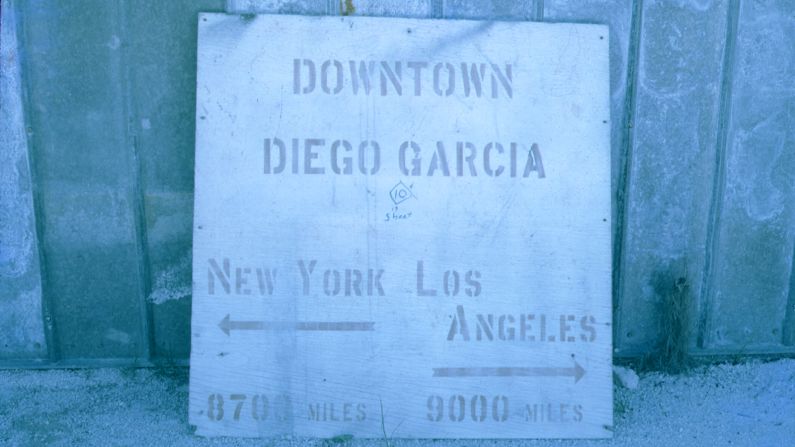

The secretive Diego Garcia military base may be 1,000 miles from the nearest continent, but it has all the trappings of a modern American town.

The troops here can dine on burgers at Jake’s Place, enjoy a nine-hole golf course, go bowling or sink a cold beer at one of several bars. The local command has nicknamed the base the “Footprint of Freedom.”

But while cars here drive on the right side of the road, this is not American soil: It is, in fact, a remote remnant of the British Empire.

That is because in 1965, in the middle of the Cold War, the United States signed a controversial, secret agreement with the British government to lease one of the 60 or so Indian Ocean atolls that make up the Chagos Islands to construct a military base.

That deal was secret because the UK was in the process of decolonizing Mauritius, of which the Chagos archipelago was a dependency.

The Chagos Islands never got its independence day. Instead, it was cleaved from Mauritius and renamed the British Indian Ocean Territory, a move that the United Nations’ highest court in 2019 ruled was illegal under international law.

Britain has now been instructed to properly finish the process of decolonization, and return the Chagos Islands, located half way between Africa and Indonesia, to Mauritius.

The ruling, though non-binding, potentially creates a huge problem for the United States. Today, Diego Garcia is one of America’s most important – and secretive – overseas assets.

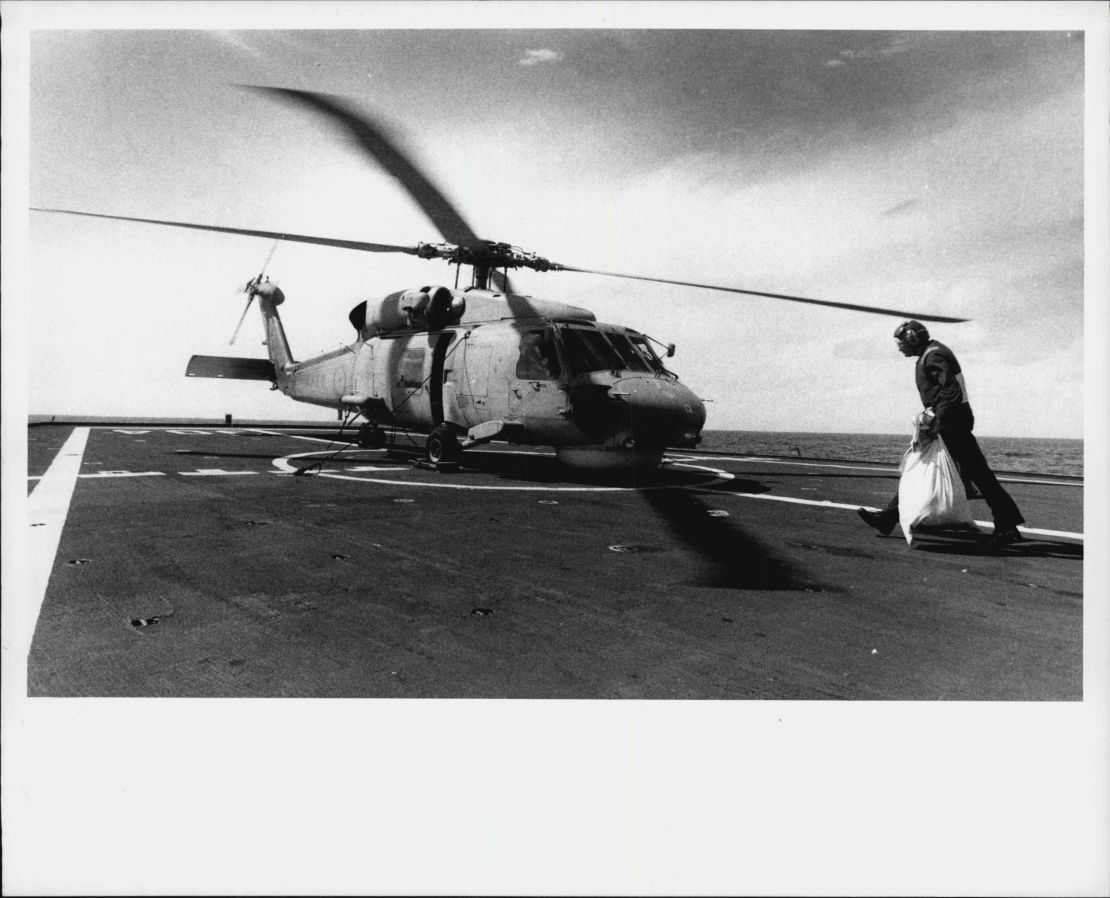

Home to over 1,000 US troops and staff, it has been used by the US Navy, the US Air Force and even NASA – the island’s enormous runway was a designated emergency landing site for the space shuttle. Diego Garcia has helped to launch two invasions of Iraq, served as a vital landing spot for bombers that fly missions across Asia, including over the South China Sea, and has been linked to US rendition efforts.

Many in Britain, including Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the country’s opposition Labour Party, are now calling for the UK to return the islands to Mauritius. Should that happen experts believe the ownership of Diego Garcia could be up for negotiation – a move that would make Mauritius a much more important country geopolitically.

A UK Foreign Office spokesperson said that the government would look at the judgment “carefully.” “The defense facilities on the British Indian Ocean Territory help to protect people here in Britain and around the world from terrorist threats, organized crime and piracy,” the spokesperson added.

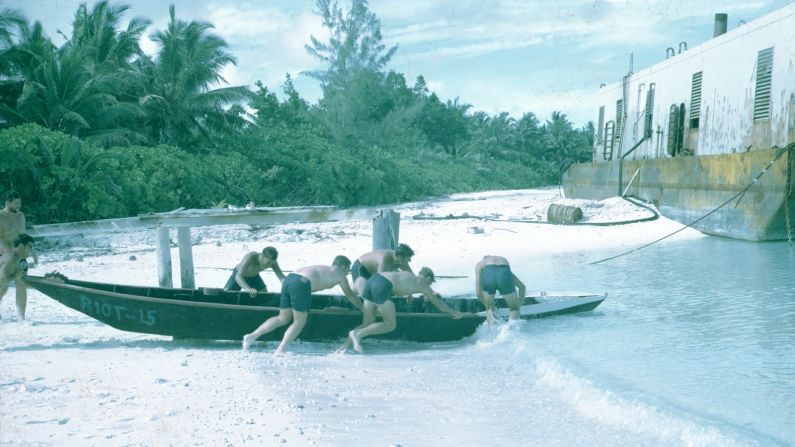

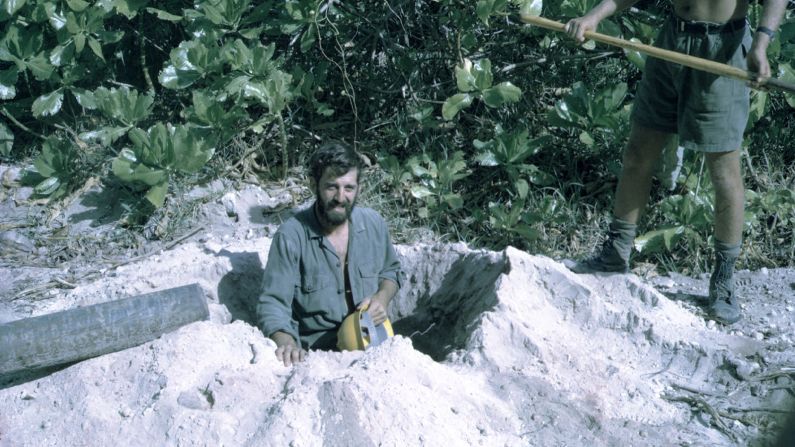

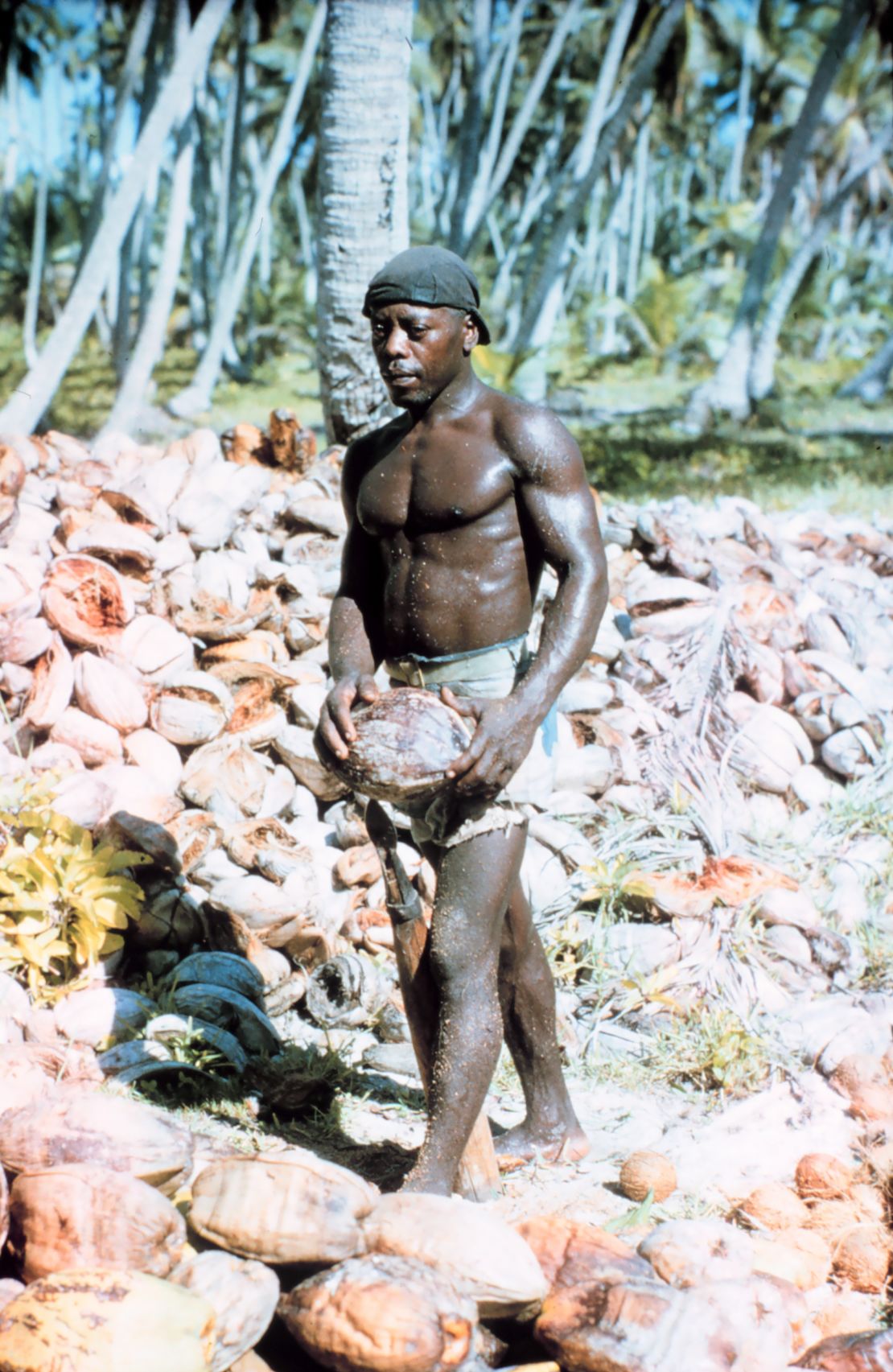

Tom Grenier was stationed at Diego Garcia in 1974 with USN Seabees. These are his images of Diego Garcia.

Covering all bases

From Singapore to Djibouti and Bahrain to Brazil, today the US operates about 800 military bases and logistical facilities outside its sovereign territory – more than any other nation.

“If you take all the other foreign bases owned by countries together there are only about 30,” says Daniel Immerwahr, a professor of history at Northwestern University.

Most of America’s bases were acquired during the era of decolonization, after World War II, when traditional colonial powers such as Britain and France were shedding colonies around the world, especially in Asia.

As Soviet influence increased during the Cold War era, the shrinking global footprint of its European allies made the United States and its allied partners worried that the West was “losing control of the world,” explains David Vine, author of “Island of Shame,” which documents the fate of the Chagos archipelago.

It was perhaps no coincidence that during this period America began what experts say was a concerted attempt to create a network of bases and facilities that offered military protection without the burden of ruling a colonial population.

“If you look at all the land globally occupied by the US, it’s not very much land mass, smaller than the state of Connecticut,” says Immerwahr, author of “How To Hide An Empire.”

“But, nevertheless, there are hundreds of points in foreign countries that the US controls and which are really important in protecting its power today.”

Many governments, such as South Korea, Japan and Bahrain, have sought long-term defense agreements with the US, viewing an additional military presence as a necessary means of protection.

In 1964, America approached Britain about leasing a tiny dot in the India Ocean.

“At the outset, the US didn’t particularly know what they would do with it,” says Vine. “It was a hedge for the future.”

In 1966, Britain and America signed an agreement without congressional or parliamentary oversight, which gave the US the right to build a military base on Diego Garcia, until its need for military facilities had disappeared – wording that was perhaps deliberately vague.

Mauritius was given £3 million ($3.9 million) for agreeing to the deal, and it was settled that America waive $14 million relating to an order of Polaris submarine missiles heading for England.

There was just one problem. The 3,000 Chagosians who lived on the islands.

‘Here go some few Tarzans’

In a 1966 memo, as Britain prepared to hand the Chagos Islands to the US, British civil servant Paul Gore-Booth wrote that the aim of the exercise was “to get some rocks which will remain ours.”

To which British diplomat Dennis Greenhill replied, in a cable brutally maligning the population of the Chagos Islands: “Unfortunately, along with birds go some few Tarzans … whose origins are obscure and who are hopefully being wished on to Mauritius.”

Had Greenhill illuminated himself he would have learned that the first inhabitants of the Chagos Islands were slaves shipped from Madagascar and Mozambique to work on coconut plantations by the French in the 18th century. After the Napoleonic wars, France ceded the Chagos Islands to Britain.

The Chagosians developed a pleasant lifestyle distinct to that on Mauritius, where back-breaking work was endured on sugar plantations, says Vine. They developed their own version of the Creole language, schools for their children, tended private gardens and led a peaceful way of life.

In 1967, the US and UK began tearing that life apart, exiling all the inhabitants from their land.

“Initially, people who went for special medical treatment to Mauritius were just never allowed to come back,” says Pierre Prosper, who was born on Peros Banhos, a northeast atoll of Chagos. “So a mother who gave birth would be left in Mauritius while the rest of the family would be in Chagos.”

Medical and food supplies to the island were gradually restricted, until eventually, in 1973, all those remaining were told they had to leave “overnight,” Prosper says.

According to witness testimony provided to CNN by former residents, the Chagosians were herded into the hold of two cargo ships, then dumped on the quayside in Mauritius or the Seychelles. The pets they left behind were rounded up by soldiers and gassed. Their houses left to the jungle.

“People were living in cemeteries or in cattle houses, anywhere they could get a roof over their heads,” says Isobel Charlot, whose family wound up in Mauritius. “The Chagos Islands were beautiful. Going to Mauritius abruptly made them depressed, many became alcoholics.”

In the 1980s, the UK paid some $5.2 million to more than 1,300 islanders on the condition they renounce their right to return.

Repeated indigenous exile

The exile of the Chagosians was not an isolated incident.

In 1946, 167 natives of the Bikini Atoll were persuaded to leave their paradise chain of 23 coral islands with twisting palm trees and aquamarine waters, after Commodore Ben H Wyatt, the military governor of the Marshall Islands, to which the atoll belonged, told them their land was needed for “the good of mankind and to end all world wars.”

In reality, that meant dropping 23 nuclear weapons on Bikini between 1946 and 1958, as part of the Cold War nuclear arms race – including the most powerful explosion ever detonated by the US.

The islanders were shipped to Rongerik, an uninhabited atoll about 100 miles away, and left food supplies for a few weeks. But crops on the Bikinians’ new home produced significantly less food than those on Bikini, and the nearby waters had far less edible catch.

Within two years, the population was on the verge of starvation.

In 1948, the US responded to their plight. Once more the Bikinians were uprooted – this time to Kwajalein, where they lived in tents next to a cement airstrip used by Americans. Six months later, they were shipped to Kili Island, 400 miles south of Bikini, where they again began to starve.

One attempt was made to resettle the Bikinians in the late 1960s when some 150 residents were returned to their atoll. But in 1978 it was revealed that within one year some residents had seen a 75% increase in radioactive material in their bodies, and all residents were once again moved, this time to Majuro Atoll.

In the early 1980s, the Bikinians filed a class action lawsuit against the US, which eventually resulted in the creation of a $90 million trust fund for their local government for cleanup and resettlement purposes.

‘Geopolitical manspreading’

When the US military decides to build a base it commits the “geopolitical equivalent of man spreading,” says Immerwahr – “taking out quite a lot of space for low density uses.”

So, on the Chagos Islands, for example, all of the inhabited atolls had to be cleared despite the fact only one would be used by the Americans.

In 2015, Canadian photographer Diane Selkirk moored her sailboat off Ile Boddam in the Chagos archipelago – sailors who seek permission from the British Indian Ocean Territory can stay for one month.

Selkirk describes a place more pristine than any Maldivian resort, where she waded among shark nurseries in the shallows and snorkeled through “the most diverse schools of fish” she’d ever seen. In the day, she explored abandoned schools, homes and churches, overgrown by jungle on the depopulated atolls.

“But the gravity of being permitted to use the nation of an exiled people as our personal tropical playground felt deeply wrong,” says Selkirk.

“From the US perspective, says Immerwahr, local populations like the Chagosians were “a problem.” The government’s aim was to create a quarantine zone around the base on the Chagos archipelago, where local people could not infect the operation.

Life on Diego Garcia

The hedge the Americans took on Diego Garcia soon began to pay off.

After the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979, Diego Garcia underwent the biggest expansion of any US military location since the Vietnam War, becoming fully operational in 1986.

One of the first things the US military did was deepen the harbor, says CNN military analyst Cedric Leighton, who was stationed on a US base on the island of Guam in the Western Pacific in the 1990s, from where he provided logistical support to Diego Garcia.

Today, that harbor is big enough for an aircraft carrier to use, says Vine. “There are also massive pre-positioned ships in the lagoon, each about the size of the Empire State Building, filled with enough weapons and supplies for material tanks, helicopters for an entire brigade of Marines.”

The military also built a 12,000-foot (2 mile) long runway capable of hosting B-1, B-2 and B-52 bombers.

Within weeks of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, the base received an additional 2,000 Air Force personnel, says Vine, and a 30-acre housing facility was built for the newcomers named Camp Justice.

Diego Garcia is also one of a handful of stations running the US military’s Global Positioning Systems. “If there is any type of conflict in space, Diego Garcia is important in the physical sense and the communications sense,” says Leighton.

“One of the jokes about Diego Garcia is that it’s basically a floating aircraft carrier. You could almost say the same about Guam,” he adds.

But, of course, Guam has a local population, a civilian airport, doesn’t boast such close proximity to the Middle East – and crucially doesn’t have such a remote location.

Secret base

Thanks to being miles from anywhere, Diego Garcia has become notorious for its mystery.

Leighton says that while military personnel based on Guam could bring their spouse, those working on Diego Garcia, which is just 38 miles long, had to go alone.

No journalists have ever been, although a Time magazine correspondent filed a dispatch from the tarmac, after he touched down there for a quick refueling stop while aboard Air Force One with President Bush. The reporter described it as “paradise in concrete.”

The only people permitted onto the island outside military personnel are the largely Mauritian and Filipino contract staff, who cook and clean for the Americans.

The reason for a level of secrecy higher than on nearly any other US military facility – even Guantanamo Bay, which journalists have been allowed to visit – has caused many to question what happens at Diego Garcia.

In 2008, after years of denials and claims that the relevant flight logs had been damaged by water, the British government finally admitted that two CIA rendition flights containing detainees had transited through Diego Garcia in 2002.

Lawrence Wilkerson, who was chief of staff to US Secretary of State Colin Powell between 2002 and 2005, later told Vice News that his CIA contacts had indicated “interrogations took place” on Diego Garcia as part of the CIA’s rendition efforts.

The US Senate’s damning 2014 report on CIA black sites, the culmination of a five-year investigation that shed light on the CIA’s interrogation techniques, did not mention Diego Garcia.

In 2008, then CIA director Michael Hayden said in a statement: “There has been speculation in the press over the years that CIA had a holding facility on Diego Garcia. That is false. There have also been allegations that we transport detainees for the purpose of torture. That, too, is false. Torture is against our laws and our values.”

Human rights investigators have long been banned from visiting.

The future

The ruling from The international Court of Justice last week is not legally binding, meaning Britain could choose to ignore it.

The matter of who holds sovereignty over the Islands, located more than 2,000 miles off the east coast of Africa, will now be debated by the United Nations General Assembly – which referred the case to the ICJ despite London’s protests.

Stephen Robert Allen, who specializes in international law relating to the Chagos Islands, says that “it will be a very significant thing if the UK decided to ignore such a ruling.”

“As the UK forges a path post Brexit these political matters are going to be significant. Adhering to the international rule of law is going to be even more important than it would have been otherwise,” he adds.

Pravind Jugnauth, the prime minister of Mauritius, called the ruling a “historic moment for Mauritius and all its people” and said that it paved the way for the Chagossians and their descendants to “finally be able to return home” – something they have been campaigning for legally for decades.

The Mauritian government did not respond to CNN’s emails and phone calls.

CNN emails and phone calls to the UK Foreign Office requesting comment on the rendition at Diego Garcia and the expulsion of the people of the Chagos Islands were not returned.

For Emmanuel Ally, a 21-year-old law student living in London who was born in Mauritius after his family was evicted from the Chagos Islands, it’s not even about being able to repatriate to Chagos.

“It’s not about going back anymore because it’s been so long,” he says. “The question would be about having a country you could visit or go and stay there. Just knowing that the island is not a military base anymore would be great.”

Leighton, who was based in Guam, believes the chances of Mauritius evicting the Diego Garcia military base is minimal, as leasing it would earn the government important revenue and, potentially, military protection.

But there is nothing to say that the Mauritians will continue to lease the base to the same country.

“This could potentially get into an area where there is a degree of competition between the US and China when it comes to access to the Indian Ocean,” he says.

For Isabol Charlot, who now resides in London, the dream is for Chagosians to be allowed to return to Chagos. “Already, Diego Garcia has people living there. So why can’t I as well?”