Hollywood moviemakers may have to rethink their intergalactic tactics as new scientific research suggests blowing up asteroids on a collision course with Earth may be trickier than previously believed.

According to researchers from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, asteroids are considerably tougher and require a greater force of energy to destroy them than scientists had calculated.

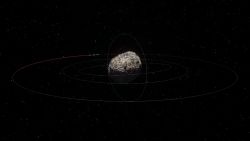

The conclusion was reached after simulating the collision of two asteroids: a target asteroid, with a diameter of 16 miles (25 kilometers), and a smaller asteroid with a diameter of under a mile, which struck the target at a velocity of three miles per second.

The experiment suggested that instead of the small asteroid shattering the larger one, as previous experiments predicted, the large asteroid remained relatively undamaged.

“We used to believe that the larger the object, the more easily it would break, because bigger objects are more likely to have flaws,” Charles El Mir, an author of the study and a researcher with the Whiting School of Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said in a statement. “Our findings, however, show that asteroids are stronger than we used to think and require more energy to be completely shattered.”

The findings may have cast doubt on Hollywood’s methods for destroying earth-bound asteroids in movies such as “Armageddon” and “Deep Impact” (though the latter deals with a comet, not an asteroid), but its authors also say they have serious implications for the Earth’s security.

“It may sound like science fiction but a great deal of research considers asteroid collisions,” El Mir said. “For example, if there’s an asteroid coming at earth, are we better off breaking it into small pieces, or nudging it to go a different direction? And if the latter, how much force should we hit it with to move it away without causing it to break?”

The research suggests that previous simulations didn’t account for the slow speed of fractures within asteroids. Millions of cracks spread in the impacted asteroid, the scientists found, while parts of the rock “flowed like sand” and a crater developed.

However, when the impact of gravity on the dispersed fragments of the asteroid’s surface was examined over several hours, the researchers found that “gravitational reaccumulation” took place, meaning that the gravitational pull of the asteroid’s “large damaged core” drew the fragments back together.

The findings pose questions for scientists looking for ways to deal with asteroids heading towards Earth. “We are impacted fairly often by small asteroids,” K.T. Ramesh, director of the university’s Hopkins Extreme Materials Institute, said in the statement.

“It is only a matter of time before these questions go from being academic to defining our response to a major threat,” he added. “We need to have a good idea of what we should do when that time comes – and scientific efforts like this one are critical to help us make those decisions.”

To illustrate the potential danger Ramesh gave the example of a meteor that exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in 2013.

Albert Zijlstra, an astrophysics professor at the University of Manchester who was not involved in the study, told CNN that the “very thorough” research could offer a new understanding about the composition of asteroids.

“It may help explain why some asteroids appear to be rubble piles, fragmented by collisions,” he said. “The study finds that asteroids can survive quite significant collisions, and keep much of their mass, but very broken up.”

The study may also provide insight into the origins of the solar system. “At that time, planets were beginning to grow, starting as dust grains and becoming pebbles, rocks, mountains and finally proto-planets,” Zijlstra said. “There were lots of collision between them. This study may help understand how they survived these collisions.”