On the banks of the Mahoning River in Northeast Ohio, not far from where the first steel mill in the area once operated, sits a warehouse where the future of manufacturing is slowly taking shape.

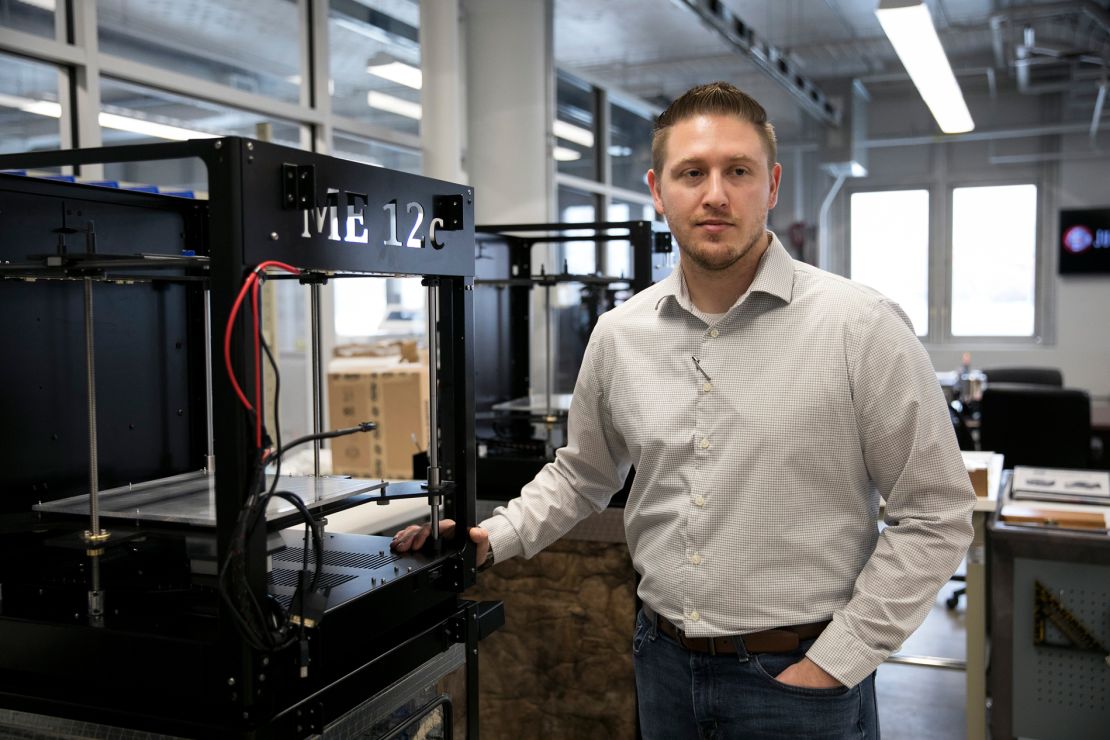

A massive 3D printer fills the space: A 12-foot by 25-foot steel plate on the floor is surrounded by 8-foot steel walls, and on top, a beam holds what looks like a giant ballpoint pen. Proprietor Michael Garvey has been test-running the machine on large hunks of black plastic, which could eventually take the shape of anything from a boat hull to an airplane wing.

It’s a far cry from the noisy, belching metal industries that once employed tens of thousands of people here — but local leaders are trying to make 3D printing technology as important to their economy as the Bessemer steel process was decades ago.

Although 3D printing is currently just a side project for Garvey, he plans to scale the business rapidly. He’s already staked out a facility where he can put several more of these gigantic, room-sized printers, fed by melted-down plastic pellets, which he figures he can bring in by railcar loads.

Unlike Silicon Valley, which has scant experience with heavy manufacturing, this faded industrial hub has all the know-how necessary to reinvent how America makes things in the future.

“With our history in Youngstown, we’ve got to learn how to adapt,” Garvey said. “We have the skill sets that we developed in a legacy industry, and we’re transitioning those skill sets to more of a 21st century digital environment.”

History is one thing, but it’s also Youngstown, Ohio’s present, with the closure this week of the Mahoning Valley’s last major manufacturer: General Motors’ Lordstown Chevy Cruze assembly plant, which employed 4,500 people as recently as 2017, plus thousands of others at local suppliers that will also shut down as a result.

In recent years, the federal government has poured money into a lively collaboration between academics and industry focused on preserving US manufacturing for the next generation. And plenty of existing companies are adopting other new technologies to get leaner and more productive. But even if they succeed, the thousands of solid, middle-class jobs that local residents could get from GM with just a high school diploma probably aren’t coming back.

Rather, the new manufacturing industry will require a smaller number of highly-educated engineers, programmers and machine operators — the types of skills that today are in short supply not just in the US, but around the world.

Garvey came back to Youngstown from a trading floor job on Wall Street in the 1980s to rescue his father’s bronze foundry, which had suffered along with the steel mills that used to line the river. He started a company that allowed those plants to run more efficiently by measuring imprecisions in the operation of their machinery, thereby reducing downtime.

The giant printer project will ultimately run using robots that talk to each other with little human involvement, known in manufacturing jargon as “Industry 4.0.” It’s part of a progression that started with water and steam power, advanced with electricity, leapt forward with computer chips, and now involves devices communicating with each other and learning on their own through artificial intelligence.

It may employ fewer people per widget produced, but the way Garvey sees it, the area has no other option.

“We are a community at risk,” he said. “And if we don’t get involved in Industry 4.0 in a substantial way, we’re pretty much sealing our fate.”

The Silicon Valley of 3D printing

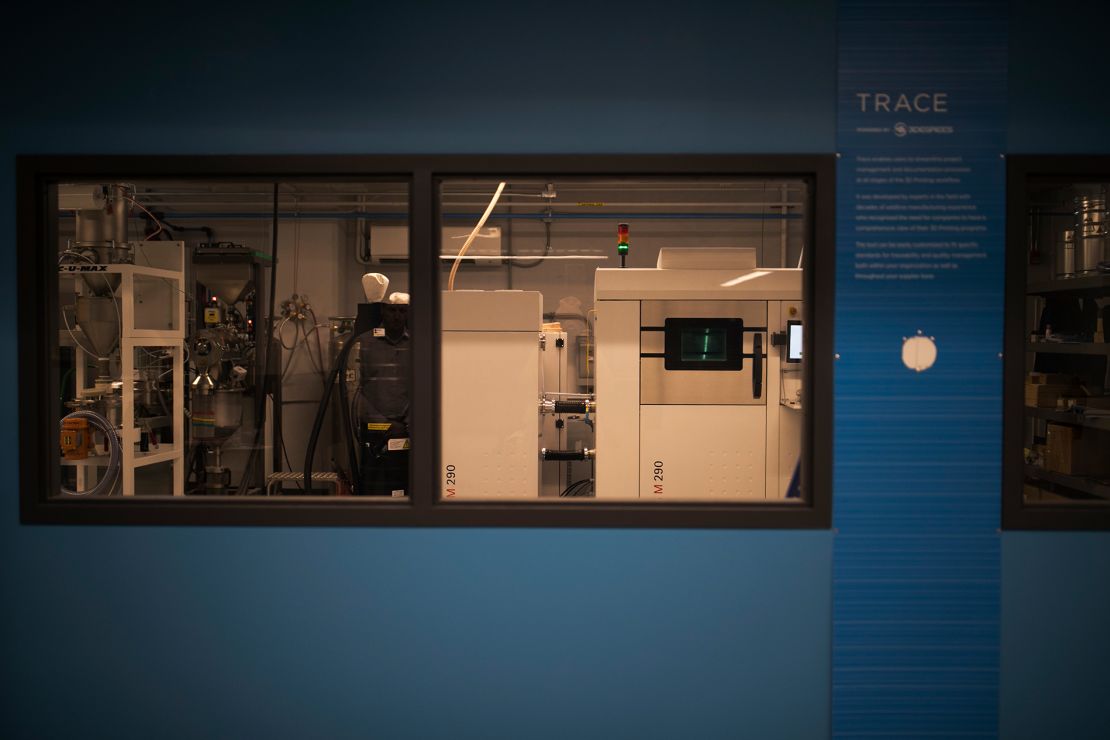

The Mahoning Valley’s transformation began in earnest in 2012, as the number of manufacturing workers in the area started rising from an all-time low, when the Obama administration put one of its five National Manufacturing Institutes in Youngstown.

This one was focused on a process called “additive” manufacturing — i.e., 3D printing. The local business incubator, which had been trying to nurture information technology startups, pivoted to focus on advanced manufacturing. So did Youngstown State University, which lured some of the best faculty in the field with more than $10 million worth of equipment.

That model, bringing in federal funding and academic brainpower, is one that’s worked well before in developing innovation clusters and enriching communities down the line. Silicon Valley, for example, couldn’t have happened without the US Department of Defense buying the microchips that Bay Area companies started to produce, or if Stanford University hadn’t fostered entrepreneurs who then patented technologies and spun out their own companies.

3D printing has been around for a decade now, and it’s still often seen as a novelty way to pump out plastic trinkets and models. People working with the technology in Youngstown, however, saw the machines as a way to extend and enhance the region’s existing industrial base, strengthening the mom-and-pop machine shops that still dot the city like corner pubs.

Take the production of all the devices needed to make things out of metal, like gauges, clamps and drill bits. Traditionally, tools and other parts are cast with molds made out of sand, producing rough steel forms that have to be further sanded down. They take several steps and sometimes weeks to make, can break easily and aren’t able to handle delicate details.

That’s why some startups at the Youngstown Business Incubator specialize in 3D printing the molds for those tools — which can take a tenth of the time — and are working with big manufacturers to incorporate the process into their production lines.

In 2014, a Youngstown State graduate named Zac DiVencenzo started a company called Juggerbot 3D at the incubator. He works with plastics companies like DSM Additive to align his products as closely as possible to what equipment manufacturers are looking for: A quick way to experiment with and produce parts, from gearboxes to pump houses. Youngstown is an ideal location, he said, as it’s less than a few hours drive from plenty of big assembly plants. “My partners might not be as close,” DiVencenzo said, “but my customers are.”

On top of making precision parts and molds for heavy manufacturing, Juggerbot sells its own proprietary 3D printer, and is experimenting with medical devices and surgical implants, like a prosthetic knee socket or a perfectly-fitted shoe insert, that can be printed to order.

Other activities at the incubator include producing spare parts for the US Air Force’s older airplanes that it can’t get anywhere else, and soon, 3D printing eyeglasses to fit peoples’ features based on a facial scan.

The point to all these endeavors is to create a flexible manufacturing base that can adapt to customers’ needs quickly, rather than the rigid assembly line at the now-shuttered GM plant in Lordstown. That plant is configured to only be able to manufacture one model of car, and shifting to something different would require millions of dollars of investment, plus months of idle time.

Incorporating additive manufacturing is also a way for smaller Youngstown companies to remain resilient and make products at a lower cost, so that when downturns come or a large client moves away, they can pivot to other markets. Factories like a large aluminum can manufacturer have gotten in touch with Youngstown State to see if there are ways they can incorporate 3D printing into their operations.

“They know their world is going to change too,” said Jim Tressel, president of Youngstown State. “Don’t know how. But they know, like Thomas Edison said, ‘there’s a better way, find it.’”

If Youngstown can turn itself into a 3D-printing manufacturing base, it will still be smaller scale and more distributed, rather than relying on enormous tent-pole companies of years past. It won’t be as visible to the outside world — but it will be less vulnerable to the whims of any one institution.

“Lordstown is very unfortunate. However, it’s the thing that everybody sees every day,” said Ethan Karp, director of a coalition of manufacturers called MAGNET. “What they don’t see is the wide world of much smaller companies in our region that are healthy and growing and improving.”

Of course, there’s no guarantee that getting an edge in additive manufacturing will turn around Youngstown’s fortunes. Even if the area becomes a global center of 3D printing innovation — YSU is hosting a worldwide conference on the technology in 2020 — other places are also pursuing the technology, and competition for talent is fierce. That’s why the university is also investing in research areas like natural gas extraction and biomechanical engineering, just to hedge its bets.

“I think it’s our big stack of chips,” said Mike Hripko, vice president of external affairs for Youngstown State, of 3D printing. “But it’s not our only stack of chips.”

Fewer man-hours, more robots

Even if technology allows manufacturing to continue in the Mahoning Valley — whether through 3D printing or other advanced techniques — it likely still won’t be the jobs dynamo that the automakers and the steel mills were at their peak.

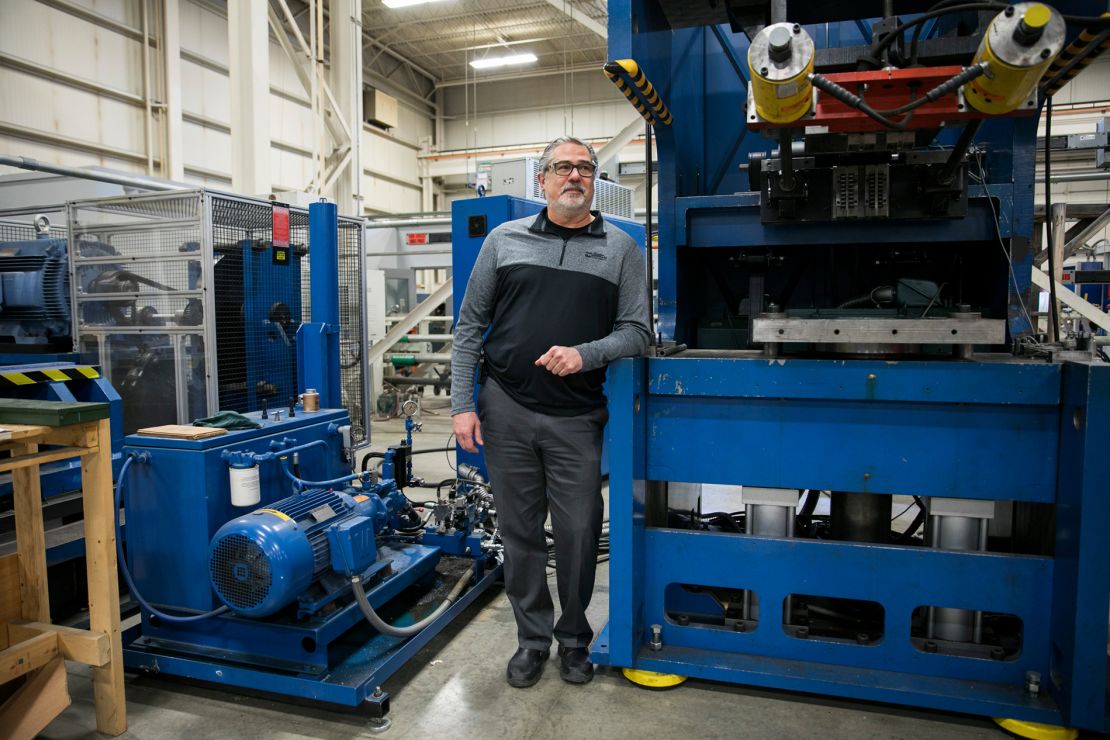

Vallourec, a French producer of steel pipes that employs 750 people on the site of the former Youngstown Sheet and Tube factory, has been automating production and removing human hands from the most dangerous parts of its process for years now.

Eric Shuster, the plant manager, said that threading pipes used to require a team of 10 workers, but now needs only seven or eight people. “There is going to be some loss,” he said. “You have to expect that. We don’t see the growth in the head count.”

Despite technological advancements that have cut down on the man-hours involved in manufacturing, the industry says it’s in dire need of workers, because the economy is doing well and a generation of people who went into the profession decades ago is now retiring. Last fall, the job openings rate climbed to its highest point on record, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That scarcity of trained workers, in turn, fuels further attempts to squeeze humans out of the process.

Taylor-Winfield is a Youngstown-based company of 87 people that’s been around for more than a century making tools and systems of tools for manufacturers all over the world. It has an R&D lab with sensors and lasers that allows teams of robots to turn out products with almost no human touch.

“What we hear time and time again is that hiring people throughout the country is difficult,” said the company’s president, Frank Deley. “So once we figure out the process, we figure out how to automate it.”

Deley hires people from local universities, reasoning they usually have family ties to the area and won’t just leave for a better salary somewhere on the coasts. It’s a strategy many companies have had to rely on, since Ohio can be a difficult place to lure people to if they don’t have some pre-existing relationship there.

In recent years, the industry has been taking this problem into its own hands.

Jack Schron runs a company called Jergens outside Cleveland, which produces hooks, racks and fasteners that hold things in place, from machines to concert speaker systems. The products haven’t changed that much, but the process of making them has. One person now tends two giant machines at once, requiring specialized knowledge and extensive on-the-job training. Schron starts people as temps, hires them on if they work out, and moves them all around the factory floor as they learn new things.

He’s also been pushing for cooperation among manufacturers, like support for shared training programs. Their graduates might end up somewhere other than the company where they gained their skills, but overall, the pool of new recruits gets bigger.

“We trust that we’ll get our fair share,” Schron said. “We have to wake up to the fact that manufacturing is not Lordstown. It’s all of us working together.”

READ MORE ON GM

And what about all the Lordstown employees being laid off? Even with manufacturers complaining loudly about how desperate they are for workers, the jobs they have to offer are often very different from the ones GM is cutting.

For one thing, they’ll require more education, which is available through various state and federal programs but difficult to undertake if you’re already over 50 and were counting on being able to finish out your working years at the plant. It may mean starting over at the beginning, where years of seniority don’t matter, and making far less than unionized auto workers did in the past.

“I think there will be some pain in that transition,” said Glenn Richardson, managing director of advanced manufacturing at Jobs Ohio, the state’s private sector economic development partner. “If you’re having to retrain, you’re coming in at an entry-level position. But I think the potential is there to get back to that.”

And right now, there aren’t a ton of training programs in 3D printing, given how new the technology is.

Barb Ewing runs the Youngstown Business Incubator, and believes in the power of entrepreneurship to revitalize the local economy — but less is known about the power to create enough work for everyone.

“How do you prepare your community for jobs that don’t even exist?” she said.