Ten years after the Kepler Space Telescope launched and revolutionized exoplanet discovery, Kepler-1658 b has finally been confirmed as the first exoplanet that the mission ever detected.

It’s taken so long because the initial estimate of Kepler-1658, the planet’s host star, was wrong. This also made the size estimate for the planet incorrect as well, and both of them were underestimated.

The incorrect numbers contributed to confusion that made the planet candidate seem like a false positive, and it was set aside. Then, University of Hawai’i graduate student Ashley Chontos focused her first year graduate research project on re-analyzing host stars of Kepler planet candidates.

Together, Chontos and an international team of astronomers have a paper on the planet that has been accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal.

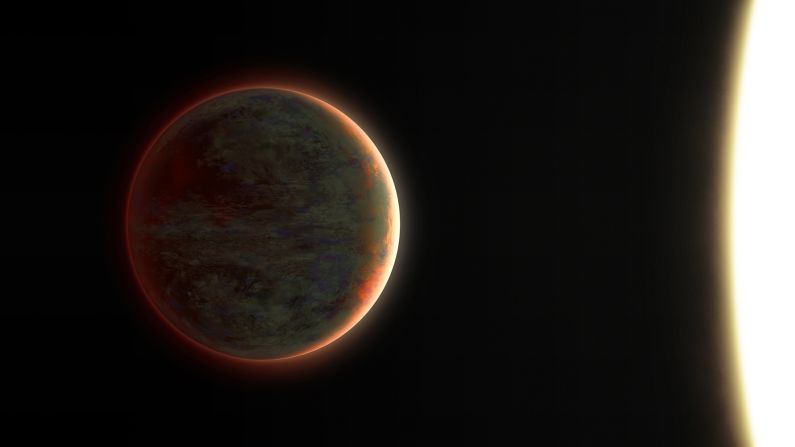

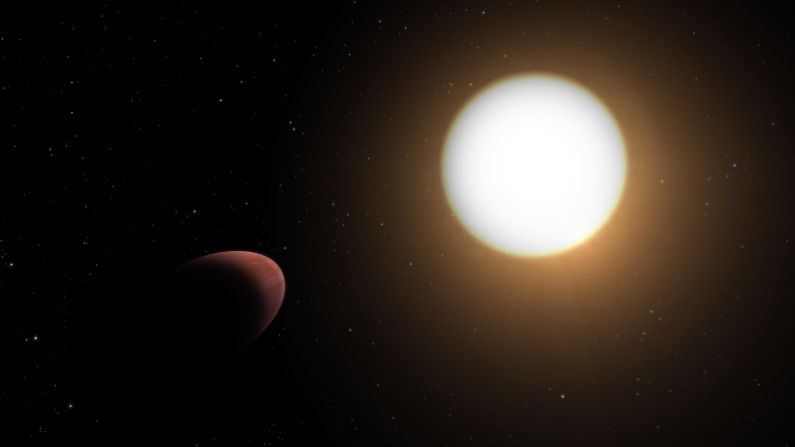

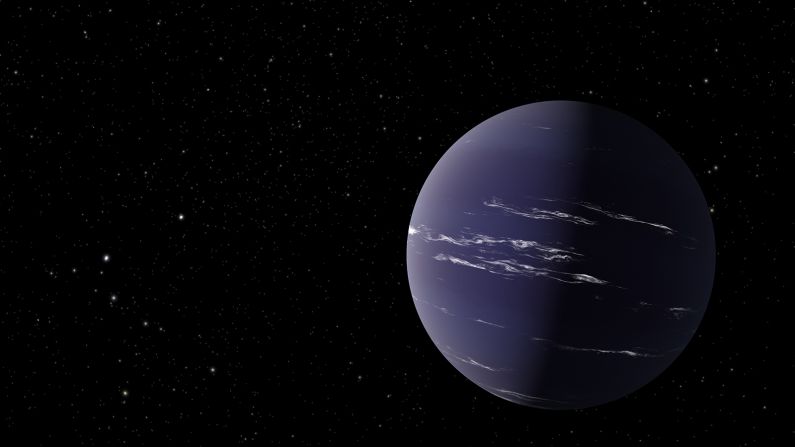

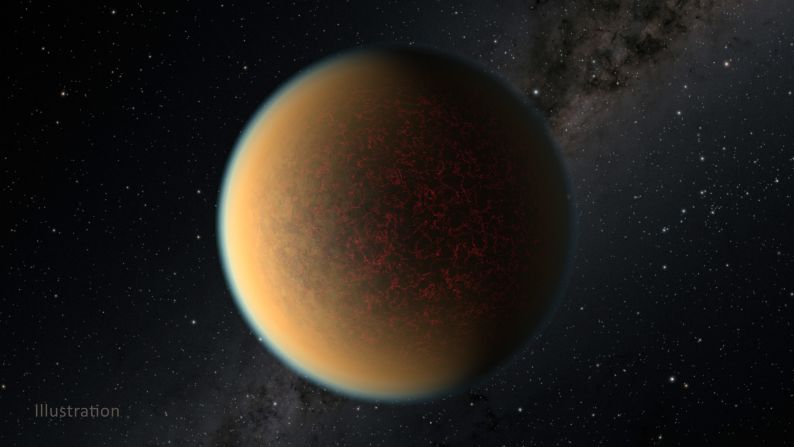

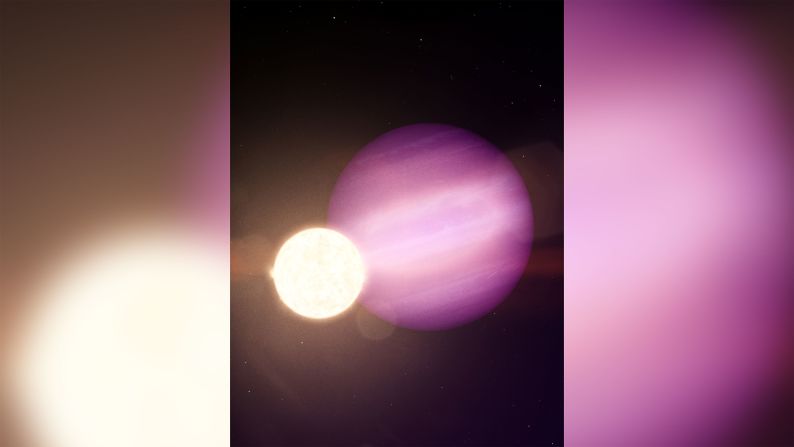

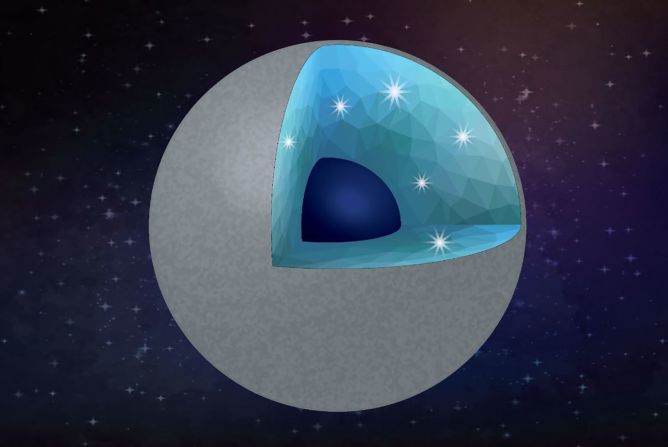

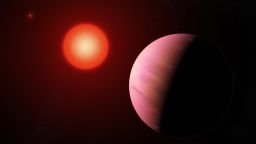

“Our new analysis, which uses stellar sound waves observed in the Kepler data to characterize the star, demonstrated that the star is in fact three times larger than previously thought. This in turn means that the planet is three times larger, revealing that Kepler-1658 b is actually a hot Jupiter,” Chontos said in a statement.

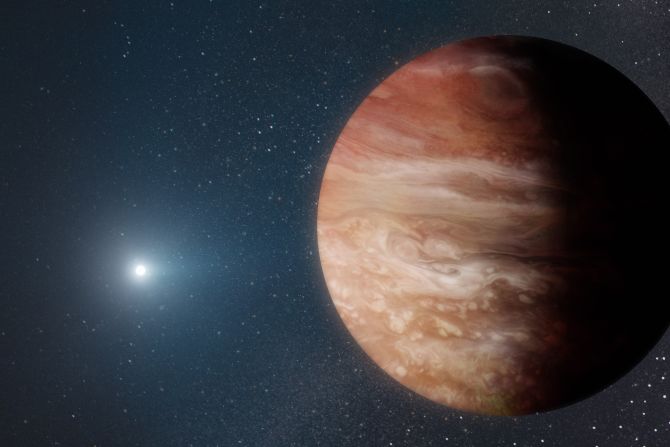

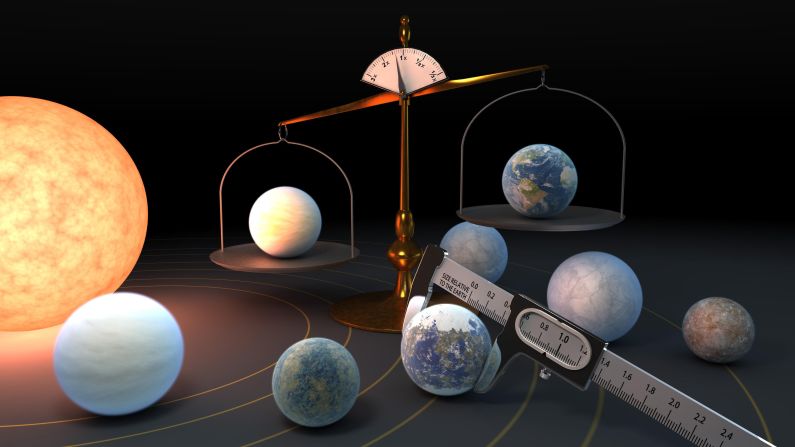

Hot Jupiters were common discoveries during the early days of exoplanet hunting because they were easy to find, but they represent only about 1% of known exoplanets now. They were replaced by smaller sub-Neptune-sized planets as the most common.

The data collected by Kepler showed that Kepler-1658 b was a planet, but they needed new observations using other telescopes to be sure.

“We alerted Dave Latham and his team collected the necessary spectroscopic data to unambiguously show that Kepler-1658 b is a planet,” said Dan Huber, co-author and astronomer at the University of Hawai’i. “As one of the pioneers of exoplanet science and a key figure behind the Kepler mission, it was particularly fitting to have Dave be part of this confirmation.”

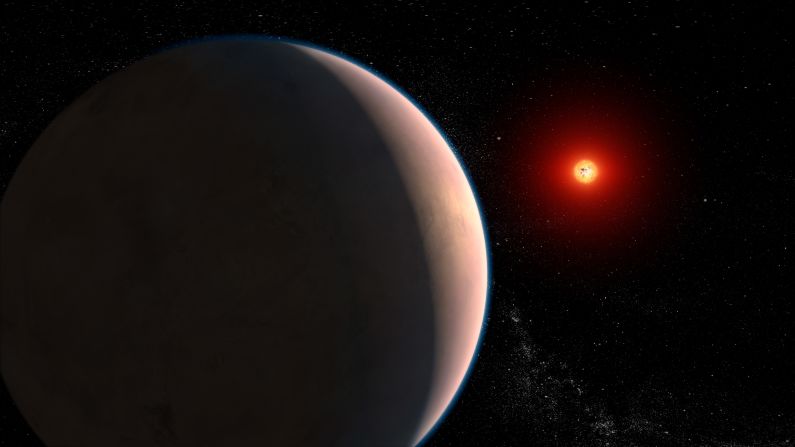

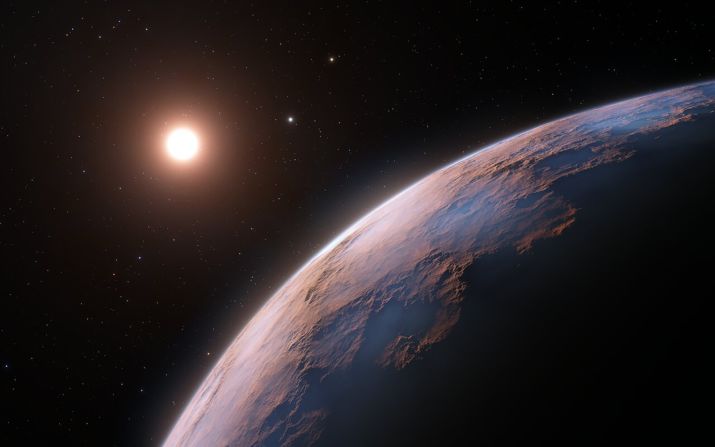

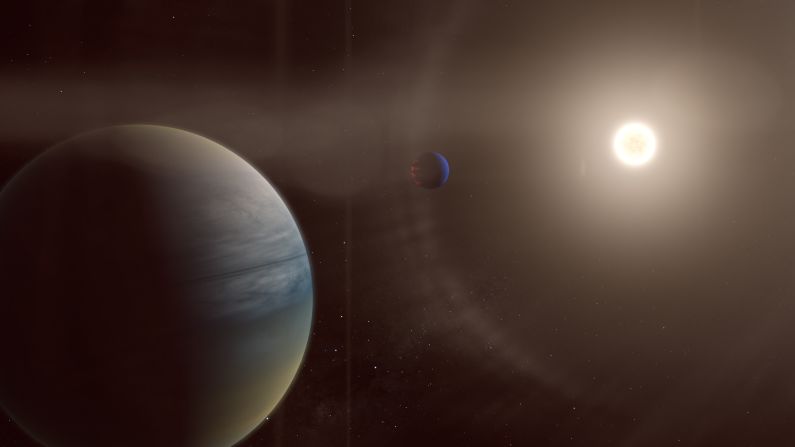

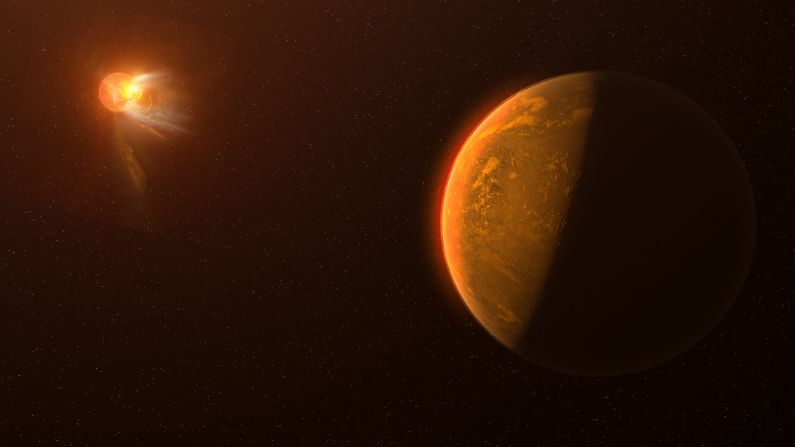

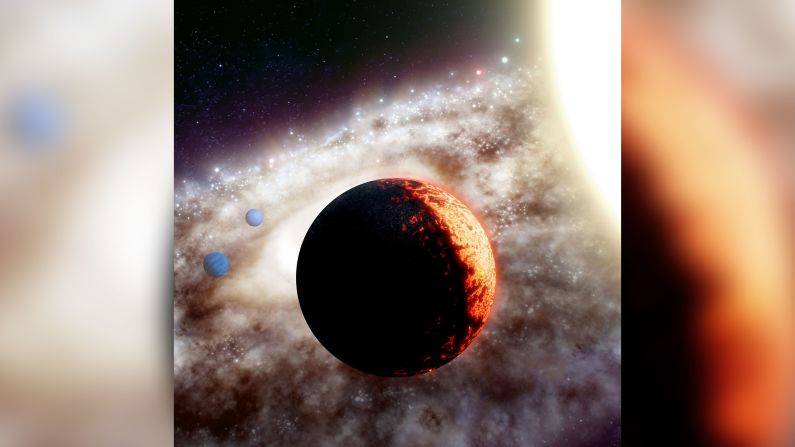

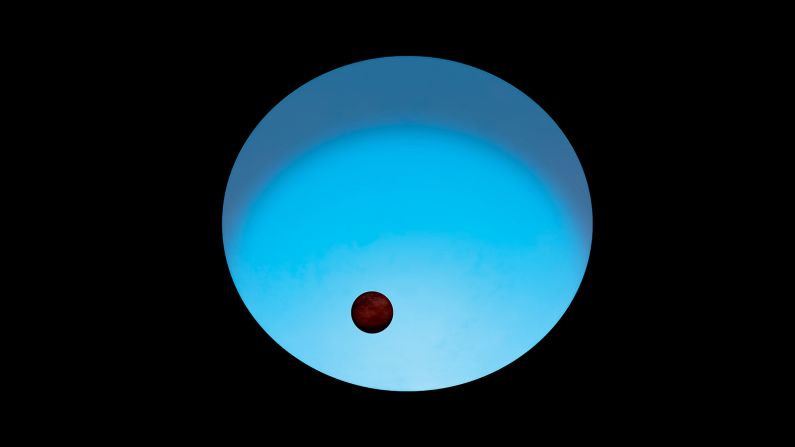

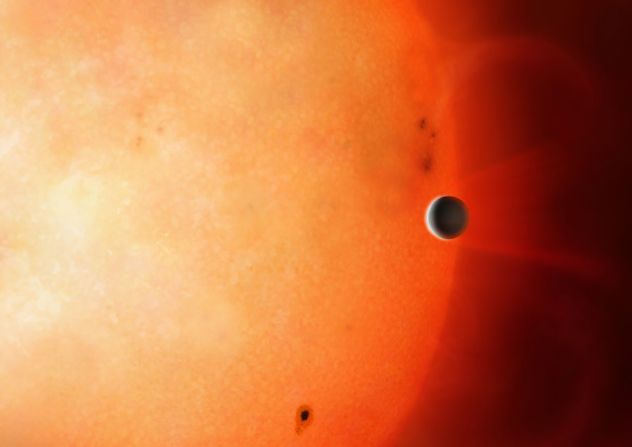

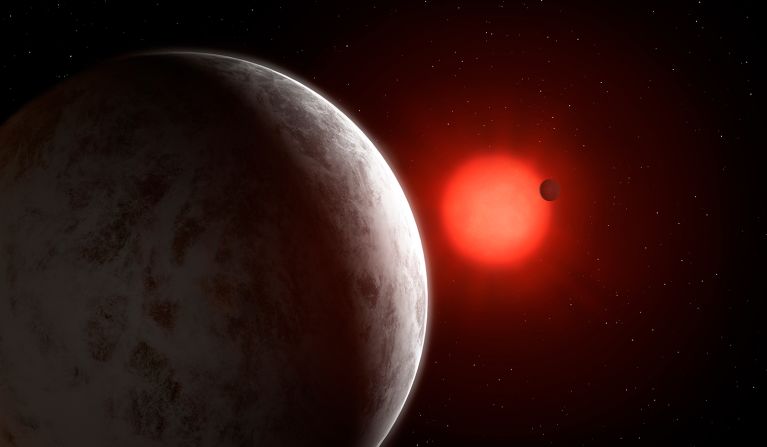

The star has 50% more mass than our sun, and it’s three times larger. The planet orbits closely, only about twice the star’s diameter away from it. This makes the planet one of the closest to its host star, which is a more evolved star that mirrors what our sun will be like in the future. The star is a massive, evolved subgiant, according to the study.

The quick orbit sends the planet around the star every 3.85 days. Giant planets with short orbits around subgiant stars are rare.

If you could stand on the planet, the star would seem 60 times larger in diameter than the sun does when we see it from Earth.

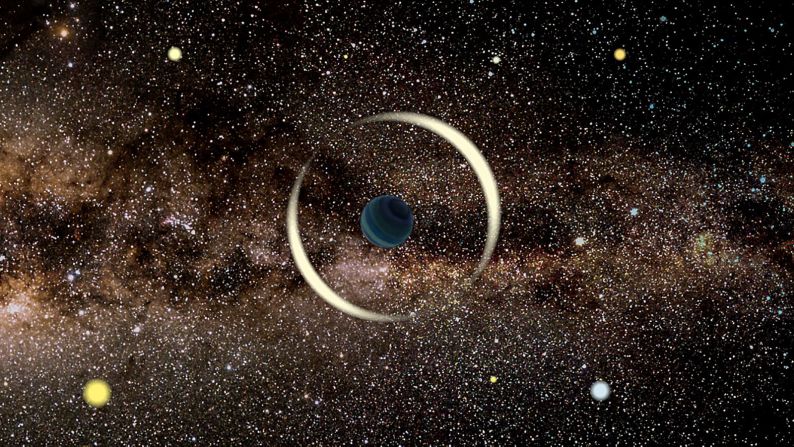

The planet is rare, although astronomers don’t know why planets orbiting evolved stars are so absent. But because the planet is so extreme, astronomers can study the processes behind what causes some planets to spiral into their host stars. That’s a possible theory as to why closely orbiting hot Jupiters are so rare.

Kepler-1658 b is ideal for follow-up observations by other space telescopes in the future to learn how hot Jupiters evolve and form.

“Kepler-1658 is a perfect example of why a better understanding of host stars of exoplanets is so important,” Chontos said. “It also tells us that there are many treasures left to be found in the Kepler data.”

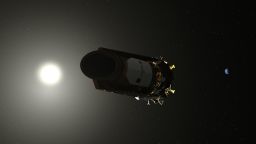

The Kepler Space Telescope ran out of fuel in October and its 9-year mission came to an end.

The planet-hunting mission discovered 2,899 exoplanet candidates and 2,681 confirmed exoplanets in our galaxy, revealing that our solar system isn’t the only home for planets.

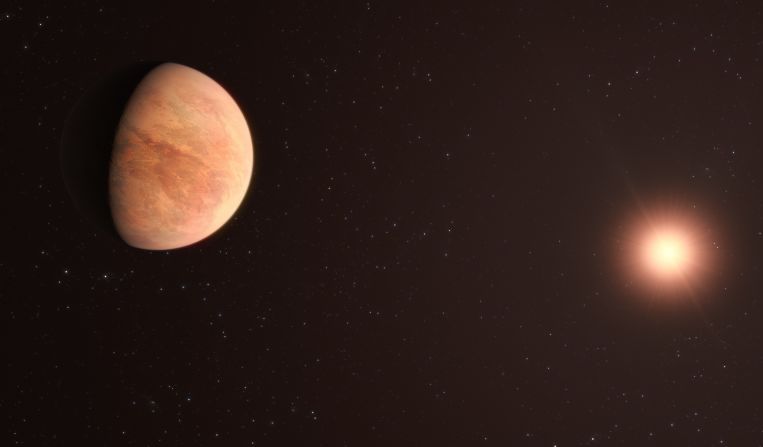

Kepler allowed astronomers to discover that 20% to 50% of the stars we can see in the night sky are likely to have small, rocky, Earth-size planets within their habitable zones – which means that liquid water could pool on the surface, and life as we know it could exist on these planets.

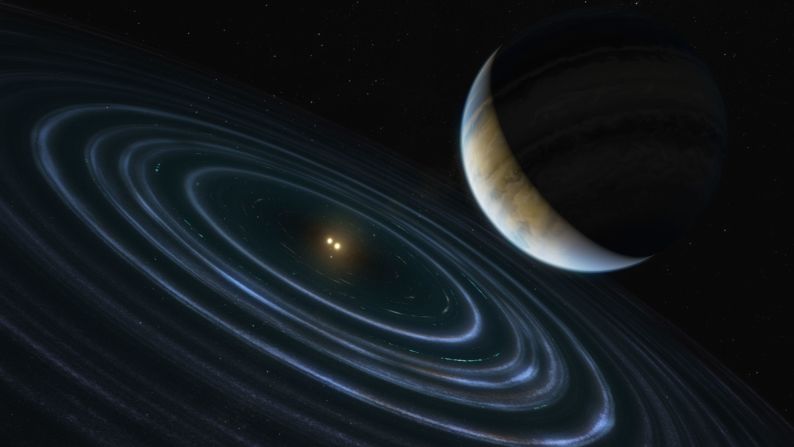

And those discoveries have helped shape future missions. TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, launched in April 2018 and is the newest planet hunter for NASA. It began science operations in late July, as Kepler was waning, and is looking for planets orbiting 200,000 of the brightest nearby stars to Earth.