The young girl on the computer screen is adorable, with rosy cheeks, blue-gray eyes, wispy red toddler hair and lips just hinting at a smile.

But she doesn’t exist in real life. She’s a face generated on a website — aptly titled thispersondoesnotexist — by artificial intelligence. If you reload the page, she’ll be replaced by another face that’s equally compelling but just as unreal.

Launched earlier this month by software engineer Phillip Wang as a personal project, the site makes use of a recently-released AI system developed by researchers at computer chip maker Nvidia. Called StyleGAN, the AI is adept at coming up with some of the most realistic-looking faces of nonexistent people that machines have produced thus far.

Thispersondoesnotexist is one of several websites that have popped up in recent weeks using StyleGAN to churn out images of people, cats, anime characters and vacation homes that look increasingly close to reality, and in some cases are indiscernible by the average viewer. These sites show how easy it’s becoming for people to create fake images that look plausibly real — for better or worse.

The problem with fake faces

Wang, like many AI researchers and enthusiasts, is fascinated by the potential for this kind of AI. So much so that he created a second site called thiscatdoesnotexist that generates faux felines. Buthe is also concerned about how it could be misused.

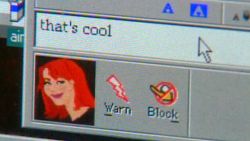

This makes sense, as the AI tactic underlying StyleGAN has also been used to create so-called “deepfakes,” which are persuasive (but fake) video and audio files that purport to show a real person doing or saying something they did not.

Those worries are echoed by prominent voices in the industry. Earlier this month, nonprofit AI research company OpenAI decided not to release an AI system it created, citing fears that it is so good at composing text that it could be misused.

But even though the images popping up on Wang’s site could be used to, say, help a scammer create realistic online personas, he hopes it will make people more aware of AI’s emerging capabilities.

“I think those who are unaware of the technology are most vulnerable,” he said. “It’s kind of like phishing — if you don’t know about it, you may fall for it.”

The allure (and tells) of fake folks

Many people aren’t quite sure how to feel about such easy access to fake faces. But they are interested in seeing them.

Wang, previously a software engineer at Uber, had been studying AI on his own for six months when he put up his website in February — shortly after Nvidia made StyleGAN publicly available. He posted about the site on an AI Facebook group on February 11. In the weeks since, about 8 million people have visited it.

“I think for a lot of people out there, they look at this and go, ‘Wow, The Matrix! Is this a simulation? Are people really in the computer?’,” Wang said.

The generator creates a new face every two seconds, Wang said, which you’ll see when you refresh the page.

“You can think of it as the AI is dreaming up a new face every two seconds on the server and displaying that to the world,” he said.

The faces visitors see vary infinitely, with a multitude of eye colors, face shapes and skin tones. Some wear lipstick or eyeshadow; a handful sport glasses. Occasionally a guy with facial hair appears; one even looked sweaty.

They have all kinds of facial expressions. Some smile, others pout or look serious. The youngest faces appear to be toddlers, but none seem to be older than middle aged.

Asrealisticas these faces may appear, there are still plenty of details that give away that they are not actual people. For instance, teeth often look a bit strange and like they are in dire need of braces, and accessories such as earrings might appear on just one ear. Frequently, a person will appear to have an otherworldly skin condition or serious facial scars. Clothing can look blurry, have swirls of colors, or just kind of, well, weird.

How the faces are made

In order to generate such images, StyleGAN makes use of a machine-learning method known as a GAN, or generative adversarial network. GANs consist of two neural networks — which are algorithms modeled on the neurons in a brain — facing off against each other to produce real-looking images of everything from human faces to impressionist paintings. One of the neural networks generates images (of, say, a woman’s face), while the other tries to determine whether that image is a fake or a real face.

Although the field of AI spans decades, GANs have only been around since 2014, when the tactic was invented by Google research scientist Ian Goodfellow. They’ve quickly gained prominence among many researchers as a major advance in the field.

StyleGAN is particularly good at identifying different characteristics within images — such as hair, eyes, and face shape — which allows people using it to have more control over the faces it comes up with. It can result in better-looking images, too.

GANs-produced fakery can be fun — if you know what you’re looking at — and potentially big business. A startup called Tangent, for example, says it is using GANs to modify faces of real-life models so online retailers can quickly (and realistically) tailor catalog images to shoppers in different countries rather than using different models or Photoshop. A video game company could use GANs to help come up with new characters, or iterate on existing ones.

This is not an Airbnb

Christopher Schmidt, a software engineer at Google, was one of the millions of people who saw Wang’s site soon after it launched. He noticed that Nvidia researchers had also trained StyleGAN to come up with realistic images of bedrooms and had the idea to build his own site, thisrentaldoesnotexist, to combine ersatz room images summoned by AI with AI-generated text. The text generator he used was trained on a bevy of Airbnb listings.

Nvidia declined to comment for this story. A spokesman said this is because the company’s StyleGAN research is currently undergoing peer review.

Looking and sounding like bizarre, confused versions of vacation rental listings, Schmidt’s AI-spawned results are way less believable than the faces on Wang’s site. (One included an image of a Dali-esque dining room table; another incorporated the line, “Minutes from Woods area, and there is a garden or summer or relaxing glow of all the electricity products.”)

Yet Schmidt, too, hopes sites like his will make people question what they see online.

“Maybe we should all just think an extra couple of seconds before assuming something is real,” he said.