An analysis of the genetic makeup of more than 94,000 people in the United States and Europe with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s led to the discovery of four new genetic variants that increase risk for the neurodegenerative disease.

These genes, along with others previously identified, appear to work in tandem to control bodily functions that affect disease development, the study found.

“This is a powerful study, and a step forward for our understanding of Alzheimer’s,” said neurologist Dr. Richard Isaacson, who directs the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at Weill Cornell Medicine.

“Finding these new genes allows clinicians to one day target these genes with therapeutic interventions,” said Isaacson, who was not involved in the study. “It also gives us a greater insight to potential causes of Alzheimer’s.”

The study’s findings will not change anyone’s “day-to-day life or medical practice any time soon,” said Heather Snyder, the Alzheimer’s Association’s senior director of medical and scientific operations, who was also not involved in the new research.

“That said, they do give us potentially useful insights into the bodily processes that may cause or interact with the changes of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias,” Snyder added.

Unprecedented numbers

Led by a team from the University of Miami’s Hussman Institute for Human Genomics, an international consortium of researchers analyzed data collected by four centers, two in the United States and two in Europe, that make up the International Genomic Alzheimer’s Project.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Nature Genetics, was the second genome-wide association study to be performed by the group on individuals with known Alzheimer’s compared to a group of controls. The first study, published in 2013, looked at nearly 75,000 people and identified 11 gene “loci,” or locations, that had not been previously known to be associated with the development of Alzheimer’s.

By increasing the numbers to 94,000, the new study added 30% more data to the analysis, allowing the researchers to verify 20 previously found genes and add four.

How the new genes – IQCK, ACE, ADAMTS1 and WWOX – along with a previously discovered gene called ADAM10, affect the development of Alzheimer’s is under investigation. But once their specific functions are understood and examined, researchers say they will be able to begin to develop potential drug targets.

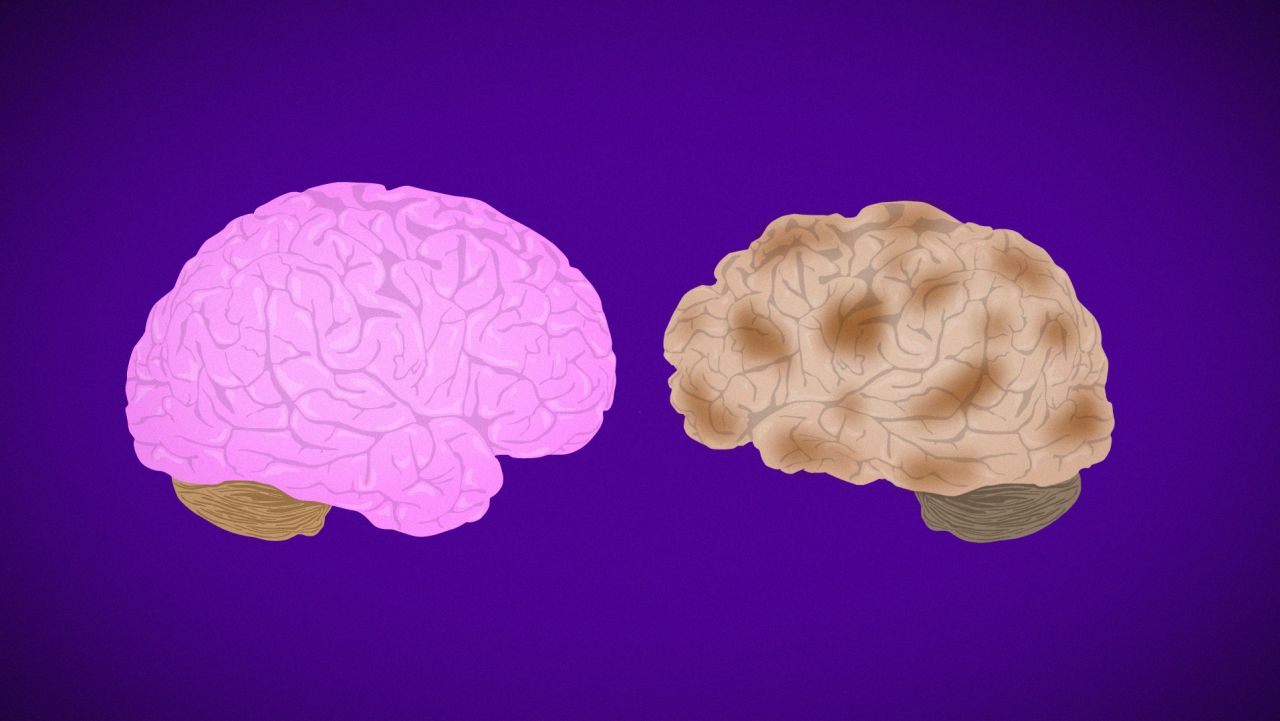

“Alzheimer’s is a complex disease. It’s not like Huntington’s or Parkinson’s, where one gene is altered and you get the disease,” said senior author Dr. Margaret Pericak-Vance, director of the Hussman Institute.

“With Alzheimer’s, it’s multiple genes acting together,” Pericak-Vance said. “We were trying to get at the very rare gene variants that could contribute to Alzheimer’s. And we couldn’t do that before. We just didn’t havethe sample size to do it.”

The study validated the previously discovered role of amyloid and immune system genes in the development of Alzheimer’s, said Harvard professor of neurology Rudy Tanzi, director of the Alzheimer’s Genome Project and a member of the international consortium.

“We had seen amyloid early on, but it had not been verified in a [genome-wide association study],” Tanzi said. “So I think one exciting thing is that it brings us back to amyloid as a major player.

“I should also say that we’re also seeing that the other major pathway besides the amyloid is innate immunity,” Tanzi said. “In this study we’re seeing even more innate immune genes affecting one susceptibility to neuroinflammation.”

A susceptibility to neuroinflammation is key, Tanzi says, “because at the end of the day, plaques and tangles may set the stage, but it’s neuroinflammation that kills enough neurons to get to dementia.”

Now having more than a dozen gene targets on how immunity ties into Alzheimer’s, Tanzi said, should “really facilitate a new drug discovery.”

Precision medicine

The increase in sample size allowed the researchers to discover “hubs of genes” that might impact the development of Alzheimer’s. “And some of those genes have the potential to have more than one function,” said lead author Brian Kunkle, an associate scientist at the Hussman Institute.

“They may be increasing risks through different disease pathways,” Kunkle said. “Prediction of risk and treatment for each individual will rely on what type of changes a person has in each of those 25 genes or other biomarkers.”

Isaacson said the ongoing work could lead to “precision medicine at its finest.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“A person can take many different roads to Alzheimer’s,” Isaacson said. “If we can find out what road a person is on through identifying certain genes, we can target specific interventions that may work preferentially for that specific person.”

As to when that might occur, Kunkle is cautiously optimistic.

“It’s difficult to say if it will help someone that has Alzheimer’s now,” he said. “Hopefully, we will have treatments developed for their family members that may have these genes that are putting them at risk.”