Black history is American history.

It’s easy to say. But while most grade school teachers agree that the experience and contributions of African-Americans are essential to understanding the nation’s past, only about 9% of total class time – about one or two lessons – gets devoted to it, a 2015 study by the National Council for the Social Studies found.

Part of why, the study found, is that teachers often lack the confidence to teach black history and aren’t sure “how and what content should be delivered.”

Certainly worthy are these trailblazers, who excelled in fields that, until they made their mark, had been off-limits to black women.

The first published poet

Phillis Wheatley was the first African-American poet to publish a book.

Born in 1753, she was brought to New England from West Africa as a slave when she was nearly 8 years old.

The Wheatley family purchased and named the young girl, and after discovering her passion for writing (they caught her writing with chalk on a wall), tutored her in reading and writing.

She studied English literature, Latin, Greek and The Bible. With the family’s help, Phillis Wheatley traveled to London in 1773 and published her first poems. Soon after, when she returned to America, she was granted her freedom.

The first college graduate

Mary Jane Patterson was 16 years old when her family, among others, moved to Ohio in hopes of sending their children to college. The daughter of a master mason, Patterson became the first black woman to graduate from an established American college, Oberlin College.

Three years after her completing her studies in 1862, Patterson was appointed a teacher assistant in the Female Department of the Institute of Colored Youth in Philadelphia, according to the African American Registry.

She later taught at the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth, renamed Dunbar High School, serving as the school’s first black principal from 1871 to 1874.

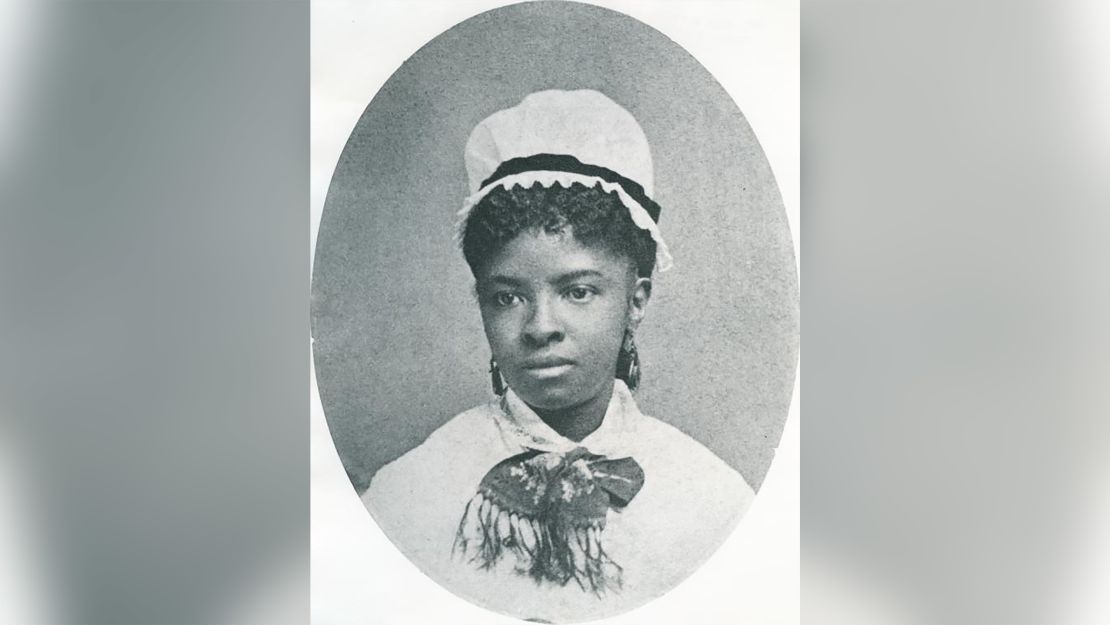

The first nurse

Mary Eliza Mahoney, born in 1845, had been a cook, a janitor and a washerwoman before she began working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, according to Jacksonville University.

When she was 33, she entered the hospital’s 16-month nursing program and earned her certification.

In a 40-year career, Mahoney directed the Howard Orphan Asylum in Long Island, New York, and was a founding member of the group that became the American Nurses Association.

After retirement, Mahoney continued to fight for minority rights and in 1920 became one of the first women to register to vote in Boston.

The first bank president

Maggie Lena Mitchell, the daughter of a former slave, went to public schools in Richmond, Virginia, became a teacher and established a newspaper before founding the St. Luke Penny Savings bank in 1903, according to the National Park Service.

In chartering the bank and serving as its first president, Mitchell broke gender and racial barriers.

She later she served as board chairwoman when the bank merged with two other Richmond banks, the park service reports. The resulting entity until 2009 was recognized as the nation’s oldest continually African-American-operated bank.

The first to refuse to give up her seat

Claudette Colvin broke ground nearly 10 months before Rosa Parks.

In March 1955, Colvin, then just 15 years old, was arrested for violating an ordinance in Montgomery, Alabama, that required segregation on city buses, according to a Stanford University entry. Colvin went to jail without a chance to call her family, a University of Idaho researcher wrote.

Colvin and other women challenged the law in court. But black civil rights leaders, pointing to circumstances in Colvin’s personal life, thought Parks would make a better icon for the movement.

“Being dragged off that bus was worth it just to see Barack Obama become president,” Colvin said in the 2017 book “Still I Rise.” “So many others gave their lives and didn’t get to see it, and I thank God for letting me see it.”

The first White House correspondent

Alice Dunnigan was mostly ignored during White House news conferences – until John F. Kennedy became President. That’s when Jet Magazine, in 1961, ran the headline, “Kennedy In, Negro Reporter Gets First Answer in Two Years,” according to The Poynter Institute, a journalism school and think tank.

Dunnigan, born in 1906 in rural Kentucky, was the daughter of a tenant farmer and a laundress. She began penning columns at just 13 years old.

She graduated from Kentucky State University and taught for 18 years before moving to Washington. In 1947, she became chief of the Associated Negro Press and the first African-American woman accredited to cover the White House, according to the Kentucky Commission on Women Foundation.

The fastest in the world

Wilma Rudolph was dubbed “the fastest woman in the world” and in 1960 became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track and field at the same Olympic Games, according to the National Women’s History Museum.

Rudolph also championed civil rights, refusing to attend a segregated homecoming parade in her honor.

Rudolph later earned a degree from Tennessee State University and was inducted into the US Olympic Hall of Fame.

The first Nobel Peace Prize winner

Kenyan ecologist Wangari Maathai became the first black woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

An outspoken environmentalist, Maathai was honored in 2004 for standing at the “front of the fight to promote ecologically viable social, economic and cultural development in Kenya and in Africa,” according to the African American Registry.

Maathai earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at American universities before completing her doctorate and founded the Green Belt Movement, the largest tree-planting campaign in Africa. She has been recognized as Time Magazine’s “Hero of the Planet.”

The first in space

Mae Jemison began studying at Stanford University when she was just 16 years old. She earned a degree in chemical engineering and in 1981 a doctorate in medicine from Cornell University.

Jemison was chosen for NASA’s astronaut program in 1987 and became the first black woman to travel in space in 1992 after launching with the Space Shuttle Endeavour crew.

Afraid of heights, she nevertheless logged 190 hours, 30 minutes, 23 seconds in space, NASA said.

The first trans politician

Andrea Jenkins in 2017 became the first openly transgender person of color elected to public office in the United States.

By the time voters chose her to serve on the Minneapolis City Council, she’d notched more than 25 years of public service experience, working as a policy aid, nonprofit director and employment specialist.

Jenkins campaigned on issues including reducing police violence, combating climate change, ending voter suppression and making available more affordable housing. She is a writer, performance artist, poet and transgender activist.