New York (CNN Business)It's a big, fat, scary round number: The national debt reached $22 trillion on Monday.

That's bigger than the entire economic output of the United States in a year. Is it time to panic?

No. But it may be time to worry a bit about the direction the debt is heading.

What is debt?

The first thing to know is that $22 trillion is a misleading number, because it includes two types of debt: The money the federal government owes to itself, and the money the federal government owes to everybody else.

The former, known as intragovernmental debt, is mostly what the Treasury owes to trust funds like Social Security. That's important, but not as important as debt held by the public, which is what can impact the economy by fueling inflation or crowding out private investment.

Right now, debt held by the public stands at $16.2 trillion. Even if you measure it as a share of the economy, that's a lot of money: It's about 76% of gross domestic product, which is very high by historical standards. It ballooned in the wake of the Great Recession, when the federal government spent liberally to save the economy from total collapse, and hasn't been paid down much since.

Another important note: The debt is different from the deficit, or the difference between what the federal government spends and what it collects in revenue each year. The debt represents the accumulation of deficits over time.

Deficits have been rising over the past several years, and jumped to 3.9% of GDP in 2019 ŌĆö the highest share since 2013, when the country was still emerging from a deep recession, in part because of tax cuts that sharply reduced government income.

Is debt bad?

Not necessarily. It depends on what you're using it for.

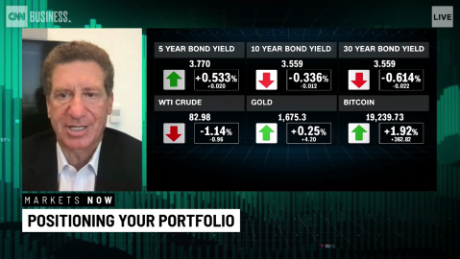

The problem with debt is that servicing it costs money. The US paid $325 billion in net interest in 2018, according to the Congressional Budget Office, which forecasts that number to jump to $383 billion in 2019 and $928 billion in 2029 under current law.

As a percentage of gross domestic product, that will approach levels not seen since the 1980s, when interest rates ŌĆö the cost per unit of debt ŌĆö were spiraling out of control. Interest rates are rising slowly now, as the Federal Reserve tapers off a period of near-zero rates. But they remain low.

It's also unusual at a time when the economy is in very good shape, raising the question of what happens when the government has to spend its way out of the next recession.

"If we go through a business cycle and we're starting at this level, then the business cycle would lead to very large deficits," said CBO director Keith Hall at a briefing with reporters last month. "I think that's a concern as a risk going forward."

However, it still could be worth it to rack up debt and pay a lot in interest, if what the government is spending money on generates a larger economic return than the cost of credit.

A shift in the economic winds

In recent months, economists have been taking another look at their longstanding consensus that high debt levels are unequivocally bad for economic growth ŌĆö a view that led to austerity budgets in both the United States and Europe following the Great Recession, which may have slowed the recovery.

Voices on the left have been arguing that governments can spend as much as they want in their own currency and control inflation through taxation. That philosophy is known as "modern monetary theory," and it has been used to explain how large spending programs such as student debt relief or the Green New Deal might be funded.

Most economists don't go that far. But they have been cautioning over high debt levels that get out of hand.

A few weeks ago, former Obama administration economic policy officials Larry Summers and Jason Furman made the case in Foreign Policy that high deficits should not be used as an excuse to cut social programs like Medicare and Social Security, and that the federal government should instead find ways to recover revenues lost to generations of tax cuts.

And at the American Economics Association's conference in January, former International Monetary Fund chief economist Olivier Blanchard delivered a keynote speech theorizing that debt might not be a problem as long as interest rates are reasonably low ŌĆö as they have been for decades now ŌĆö and government is using the money on projects that boost productivity, such as education and infrastructure.

"Both the fiscal and welfare costs of debt may then be small, smaller than is generally taken as given in current policy discussions," Blanchard wrote in a paper describing the argument.