Adeline Chan’s nose crinkled at the market’s pungent, briny smell.

Chan and her mother were once regulars at Hong Kong’s Dried Seafood Market, in Sheung Wan, where endless stalls display plastic bins stuffed with various forms of dried shark fin.

“We don’t need shark fins for ourselves, but sharks need their fins,” said Chan, now a vegan. “I stopped consuming shark fin soup four years ago after learning what sharks had to go through before a bowl of shark fin soup is served.”

But fins continue to be popular at these stores, along with other delicacies such as sea cucumbers, scallops and abalone.

According to Hong Kong’s tourism board, this seafood market has been around for at least 50 years, but the dried seafood trade can be traced to the 1860s, said Sidney Cheung, director of the Centre for Cultural Heritage Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Shark fin has long been a status symbol at Chinese dinners, particularly for wedding banquets.

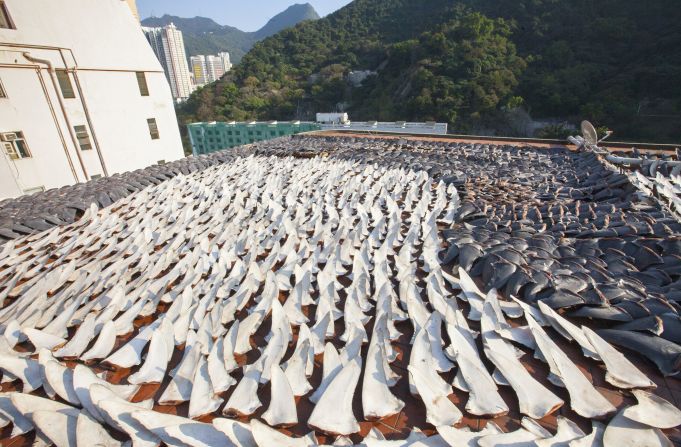

As much as half of the global supply has been found to pass through Hong Kong, the second-highest consumer of seafood in Asia at 71.8 kilograms (158 pounds) per person per year. This is more than three times the global average, according of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

And on Chinese New Year, many family dinners will include shark fin. Last year, the Hong Kong Shark Foundation found that over 80% of 291 Chinese New Year menus in Hong Kong included these dishes.

A culture of fins

For many Chinese families, culture dictates the consumption of shark fin.

“There was an old saying in Hong Kong in the 1970s: ‘To stir shark fin with rice.’ It was used to describe the lifestyle of the wealthy, implying that they were rich enough to afford shark fin on a daily basis,” said Tracy Tsang, manager of WWF-Hong Kong’s Footprint program.

“Today, the older generation still considers serving shark fin to their guests during banquets a sign of hospitality.”

Many people in China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, Macau and Vietnam all consume shark fin – primarily the Chinese population.

“The concept of ‘no fin, no feast’ is still deeply rooted in many people’s minds,” said Bowie Wu Fung, an 86-year-old Hong Kong actor who now speaks for WildAid, appearing on billboards in Hong Kong against shark fin consumption.

Funghopes to reach the older generation, who constitute the bulk of the buyers at Hong Kong’s Dried Seafood Market.

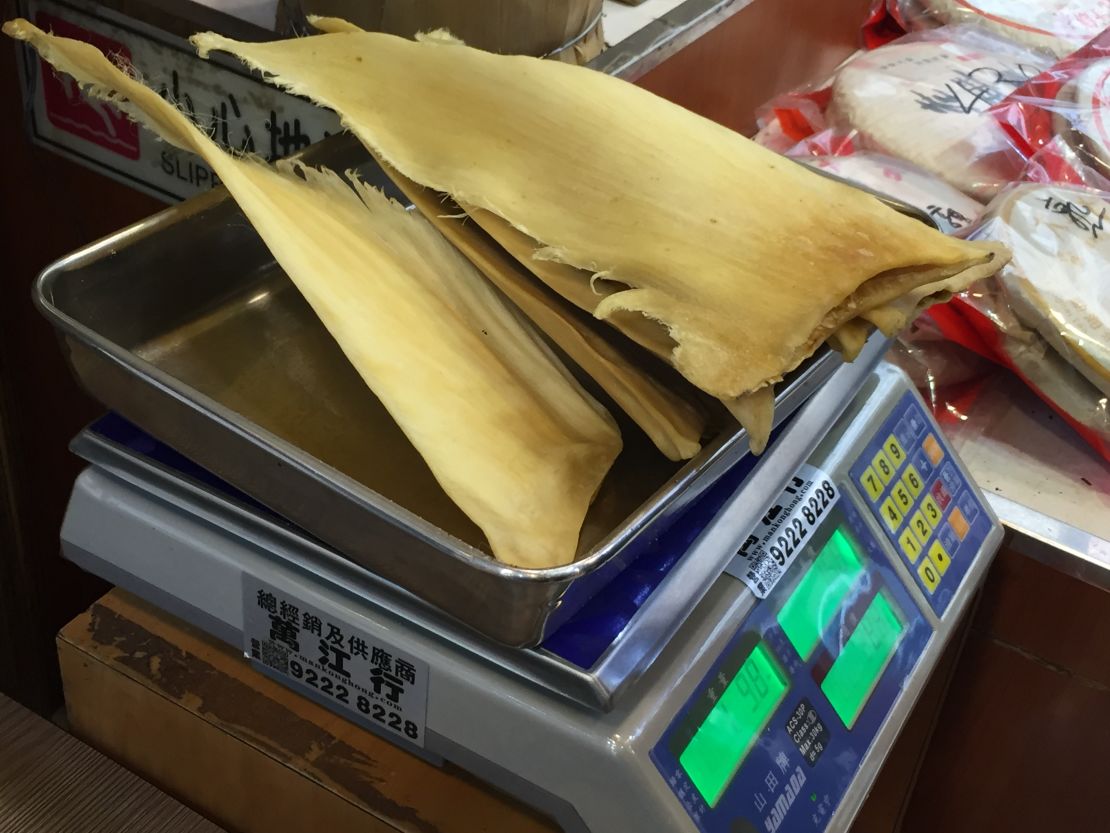

“Shark’s fin is one of the ‘four treasures’ of Chinese dried seafood, along with fish maw, dried abalone and sea cucumber,” said Daisann McLane, director of the gourmet food tour company Little Adventures in Hong Kong. “All four are expensive products that are valued for their rarity and also for their texture.”

The bigger the fin and the thicker the veining, the more expensive it is, store clerks at Hong Kong’s Dried Seafood Market said.

Prices can range from $90 Hong Kong dollars (about $12) for 600 grams (1.3 pounds) for small shredded pieces to $7,000 Hong Kong dollars (around $930) for 600 grams. According to a report released in 2016 by the conservation organization Traffic, shark fin prices can range from $99 to $591 per kilogramin Hong Kong.

On the lower end, a shark fin set lunch can cost $80 Hong Kong dollars to 90 Hong Kong dollars ($11 to $12) at Chinese restaurants, while some upscale places charge up to $1,200 Hong Kong dollars ( $160) for a bowl of shark fin soup, Tsang said.

‘A shark trading hub’

More than 1 million tons of shark are caught each year, according to a 2018 study in Marine Policy, which named Hong Kong as the “world’s biggest shark trading hub” where shark fin imports have doubled since 1960.

Nearly 60% of the world’s shark species are threatened, the highest proportion among all vertebrate groups, and the populations of some species, such as hammerhead and oceanic whitetip, have declined by more than 90% in recent years due to the shark fin soup trade, according to the study.

DNA studies have further revealed that one-third of the shark species represented on the Hong Kong retail market may be threatened with extinction.

“Sharks are in crisis,”said Andy Cornish, leader of WWF’s Global Shark and Ray Initiative. “The demand for shark fin in East and Southeast Asia and for shark meat in other parts of the world are the major drivers for the overfishing of sharks. This is, by far, the biggest cause of the shark population decline. Currently, 100% of shark fin sold in Hong Kong is from unsustainable and/or untraceable sources.”

Hong Kong customs seized at least 5 metric tons of illegal fins between 2014 and July 2018. From January to October 2018, there were six smuggling cases of endangered species of shark fins with seizure, involving a total of 236 kilograms (520 pounds) of dried shark fins, according to Hong Kong’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department.

But continued interest is putting the environment – and humans – at risk.

Ecosystem chaos

When a shark’s fin is sliced off, the animal dies, said Yvonne Sadovy, lead author of the Marine Policy study and a professor in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Hong Kong.

“It cannot move, feed or swim, so it just starves to death on the sea bottom. Maybe it is like cutting the wings off a flying plane: The plane will be destroyed,” she said.

Sharks need their fins for steering, balancing and, for some, breathing.

“There are sharks that must continue swimming to be able to breathe, as they rely on the forward motion to keep water passing through their gill slits and get oxygen,” said Stan Shea, marine program director for the Bloom Association Hong Kong, a nonprofit that works to preserve the marine environment.

When their fins are cut off, “they are likely to die of suffocation, as they are no longer able to breathe by swimming forwards. (For others), they are unlikely to suffocate but die either by starvation or watching as other animals ‘consume’ them alive.”

In addition, as apredator at the top of the food chain, sharksa are critical to maintaining balance in the ecosystem, Shea said. Its loss could cause “behavioral change” and “chaos.”

For example, when numbers of sharks decrease, their prey will increase and overeat the next level on the food chain, which is why cownose rays wiped out the scallop population in North Carolina, Sadovy said.

“Most sharks are important predators and therefore can play key roles in keeping ecosystems functioning. Depletion of sharks is expected to have negative effects on populations of prey species, many of which may be also be sharks, or rays,” said Nick Dulvy, co-chairman of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Shark Specialist Group.

‘Why the heck would you eat it?’

Eating shark meat could be harmful to humans, too.

Studies have found that sharks accumulate marine toxins, as long-lived predators at the top of the food chain. The levels of these toxins, including mercury, lead and arsenic, exceed recommended dietary levels, according to articles in Marine Pollution Bulletin.

Hong Kong’s Centre for Food Safety warned against the consumption of predatory fish species after finding a sample from a supermarket that contained a level of mercury eight times the permissible limit in 2017.

“The main food safety concern for shark fin/meat and other large predatory fish is the accumulation of mercury, especially methylmercury,” the center said in a statement.

“Methylmercury is the most toxic form of mercury affecting the nervous system, particularly the developing brain. At high levels, mercury can affect fetal brain development, and affect vision, hearing, muscle coordination and memory in adults.”

In 2016, WildAid tested samples of raw shark fin samples from Hong Kong and Taiwan’s dried seafood markets and found that all contained above the permissible amounts for arsenic and more than half exceeded levels for cadmium, a known carcinogen.

“If something damages your brain, why … would you eat it?” asked Deborah Mash, professor of neurology at the University of Miami. “There’s also no good evidence for health benefits.”

A 2016 study by Mash found a cyanobacterial toxin in sharks fins linked to the neurodegenerative diseases Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, often called ALS.

Analyzing 55 sharks across 10 species from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, her team found that the majority contained the cyanobacterial toxin β-N-methylamino-l-alanine, together with another environmental toxin – methylmercury – which is known to accumulate in sharks.

Traditional Chinese medicine may also have no need for shark fins.

“To my knowledge, shark fin is never a part of Chinese medicine practice,” said Professor Lixing Lao, director of the School of Chinese Medicine at the University of Hong Kong. “Chinese medicine community is nowadays very much aware of protection of endangered species to be used in the Chinese medicine practice.”

Besides, “shark fins have no taste on their own. It barely offers a crunchy texture when you bite into it,” said executive chef Chan Yan Tak, the first Chinese chef to get three Michelin stars, at the Four Seasons in Hong Kong, which stopped serving shark fin in 2011. “The flavor comes from the soup: a superior stock that is boiled for eight hours with Yunnan ham, chicken and pork ribs.”

Increasingly, public attitudes toward shark fin are turning.

Pushback from big voices

According to parallel studies in 2009 and 2014, consumption of shark fin in the last year surveyed in Hong Kong went down from more than 70% to less than 45%.

In contrast, the acceptability of excluding shark fin soup from weddings went up from around 78% to 92%, according to studies by the marine environment nonprofit Bloom Association of Hong Kong.

WildAid and WWF-Hong Kong estimate that more than 18,000 hotels, 44 international airlines and 17 of the 19 largest container shipping lines have stopped serving shark fin and banned it from cargo, affecting close to three-quarters of global shipments. The volume of shark fin imported into Hong Kong has also dropped by half, from 10,210 metric tons in 2007 to 4,979 metric tons in 2017, according to Hong Kong’s Census and Statistics Department.

“It was a big challenge initially, getting customers to accept our shark fin policy,” said Andy Chan, senior director of food and beverage for Shangri-La Hotels & Restaurants, which took shark fin off its menus in 2010. “We accepted that it would mean a substantial cut for our banqueting business. We initiated the policy because it was the right thing to do. We recognized that as a species, sharks are threatened with extinction, and if this happens, it would put the health of our oceans and fisheries at risk.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Joining Shangri-La in pledging to stop the sale of shark fin are Cathay Pacific, Four Seasons and, most recently, the popular Hong Kong restaurant chain Maxim’s, by 2020. The Four Seasons and some others offer a vegan version of the soup.

“As more hotels and restaurants join together in this pledge, we send a strong signal to our community and can together help to reshape dining concepts around sustainability,” Tak said.

WWF and WildAid are working to persuade more companies to make the pledge against shark fin. Recently, WildAid campaigner Alex Hofford talked to the Fulum Group, one of the largest Hong Kong chains with more than 80 restaurants, about reviewing its policies.

Citing the nonprofit’s motto, Hofford said, “when the buying stops, the killing can, too.”