Editor’s Note: Brett Bruen was director of global engagement in the Obama White House and an American diplomat. He is president of the crisis communications firm Global Situation Room, Inc. and teaches crisis management at Georgetown University. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

Disinformation did not disappear after the 2016 US election.

So, why are those responsible for responding acting like the threat dissipated? Facebook dismantled its “War Room” towards the end of last year. The US government still hasn’t bothered to put anyone in charge of tackling the issue. Much of the media coverage diminished. In this inaction, there are eerie echoes of the errors made in 2014.

After America’s elections in 2016, we spent months trying to get our heads around the scope, scale, and sophistication of what Russia had done. Congress held hearings. Law enforcement investigated. The media churned out countless stories. Social media companies denied, then tried to diminish the severity of the problem, euphemistically labeling it “inauthentic activity.”

The 2018 elections were largely a study in style over substance. Social media companies did a lot of superficial stuff by finding a few fake accounts, which provided the appearance of doing something, and gave teams cool names like the “War Room.”

We won’t know the extent of foreign influence operations in the last elections for some time. Only now, under the intense scrutiny of the Mueller investigation, are Russia’s multi-tiered, pernicious probes into the Trump campaign being revealed.

How long will it take to identify the work of 2018’s Maria Butinas and Michael Cohens? CNN recently reported that Russia was again trying to break into the Democratic National Committee last year. We know the National Republic Congressional Committee was hacked. They didn’t go public until after the elections, reflecting how many campaigns and organizations are often reluctant to bring attention to a security issue – or are just unaware when their systems are compromised.

The notion that Moscow was less active this time around is predicated on the presumption that it and others used similar tactics. In reality, tools were refined and strategies became more sophisticated. Based on research I’ve done with the Franklin D. Roosevelt Foundation at Harvard University, their tradecraft now focuses more on co-opting others to carry their water. Uncovering that kind of detached disinformation is a lot harder than what comes directly from the Kremlin’s propaganda shop.

If anything, the operations are intensifying. Indictments filed in the Mueller probe indicate Russia’s budget for information warfare has increased since 2016. Exacerbating matters, the Trump administration has not exactly won a lot of friends around the world. Countries from Iran to Cuba to China now have increased motivation to retaliate against sanctions and his strong-arm tactics. Indeed, significant foreign meddling efforts were detected during the Florida recount, Russia’s attack on the Ukrainian Navy, and France’s debilitating street protests.

For all of these reasons and many more, I was shocked to see Facebook shutter its War Room. It’ll tell you its staff remains as focused on the problem.

But imagine our nuclear threat detection center wasn’t centralized: everyone scattered around different offices, some even worked from home. We would rightly be concerned that something would be missed.

In many ways, information warfare is harder to detect than nuclear, chemical, or biological agents. Like a mythical creature, it is able to constantly change forms. Not having a group standing watch together creates gaps, delays, and difficulty in developing a high-performing team.

Despite its superficiality and myriad shortcomings, Facebook’s War Room was a start. Just like when I was back at the White House in 2014, our ragtag, rough around the edges task force against Russia was far from perfect.

But, it had gained a familiarity with Moscow’s motivations and most-likely next moves. It was a team that understood its own strengths and how best to compensate for its weaknesses. It was just starting to develop the type of tailored tools we needed for round two. It was no time to stand down.

It’s time we started getting serious about the threat. First, tech companies need to stop treating it like an episode of “Law and Order,” where occasional dramatic flair proves decisive in delivering justice.

You need sustained structures and strategies to track, defend, and, when required, go on the offensive against influence operations. Second, this isn’t a technical problem. Silicon Valley needs to reset its preset from hacking to attacking multi-faceted manipulation of their users.

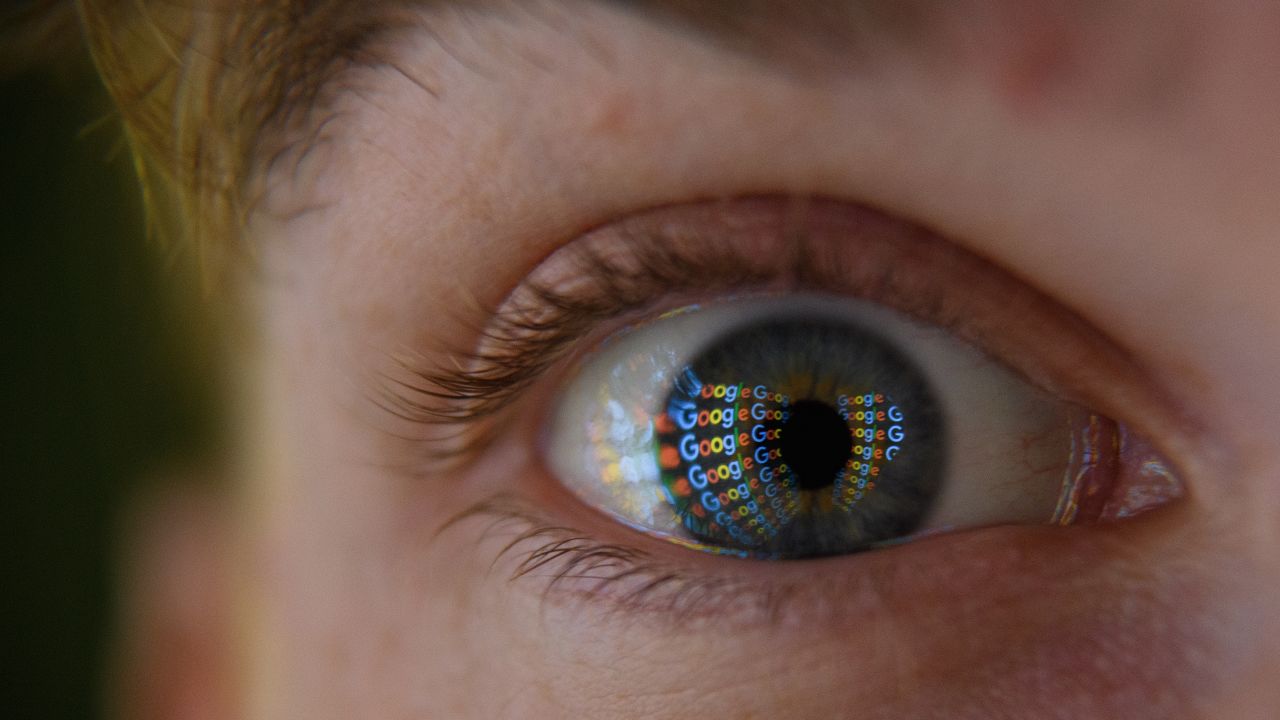

Finally, Facebook, Twitter, Google, and the rest need to start working together to tackle this threat. I have yet to see them take steps to break down communications, coordination, and collaboration barriers between the companies.

Instead, they remain stuck in a competitive race where consumers continue to come a distant second. Tomorrow, all of them could agree to set up the kind of fusion center that would make us all safer. At the very least, the world’s biggest social media platform should not be reducing its readiness to respond.

There clearly is inauthentic activity on Facebook. It includes the company’s small, self-interested, short-sighted efforts being propagandized as a real campaign to counter information warfare.